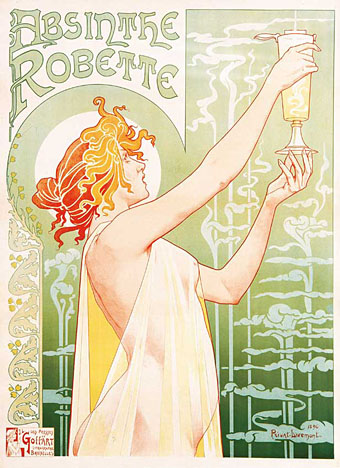

The classic absinthe poster from 1896 by Henri Privat-Livemont (1861–1936), one of the best exponents of the post-Mucha style. Don’t let anyone tell you that using unclad women’s bodies in advertising is a new thing.

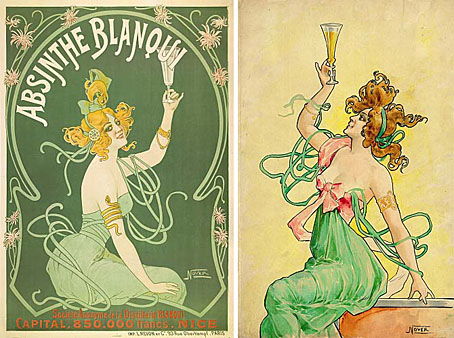

And a couple more Mucha-esque examples circa 1900, both credited to “Nover”, from the wide selection of absinthe graphics at the Virtual Absinthe Museum.

The printer was L. Revon et Cie, situated in Paris at 93 Rue Oberkampf. The artist’s signature “Nover” is a mystery—no designer by that name is recorded. Since however the word is a palindrome of Revon, the assumption must be that the artist was Revon himself, or alternatively an anonymous employee of the firm. The same artist was responsible for the well-known Absinthe Vichet poster, also printed by Revon et Cie.

Interesting that so many of these posters show the women holding the glasses aloft as though receiving a libation from the gods. Privat-Livemont’s painting adds to the sacred effect by putting a halo behind the absinthe-bearer’s head.

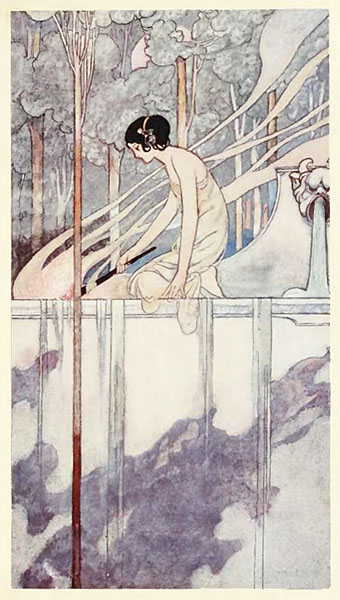

Also at the Virtual Absinthe Museum is this warning against the dangers of the Green Fairy which would make a good addition to the Men with snakes post.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• 8 out of 10 cats prefer absinthe

• Smoke

• Flowers of Love