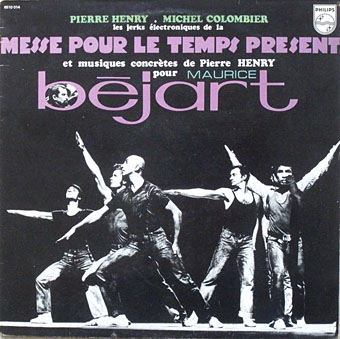

Messe Pour Le Temps Present (1967).

Electro-acoustic composer Pierre Henry probably wouldn’t thank you for calling Psyché Rock his finest moment but it’s a favourite of mine. It’s also his most well-known composition although most people know it as a putative inspiration for Christopher Tyng’s theme to Futurama. The YouTube version here is the original mix. Many other uploads are later remixes which disgracefully downplay the wonderful out-of-time synth shrieks.

Too Fortiche / Psyché Rock / Teen Tonic / Jericho Jerk (1967). Credited to “Les Yper-Sound”.

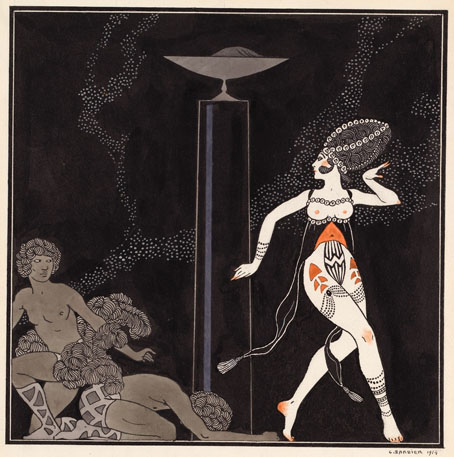

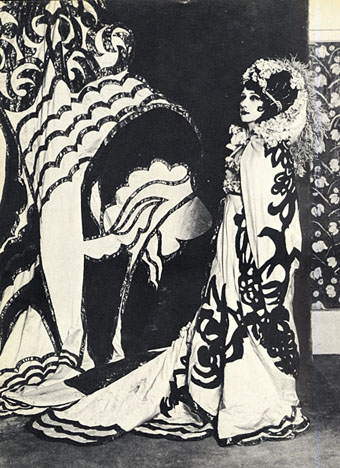

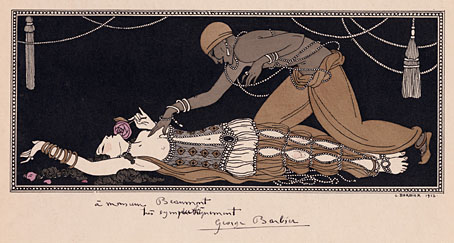

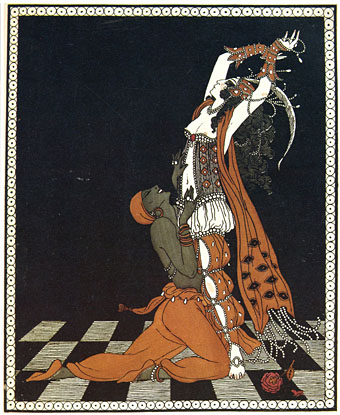

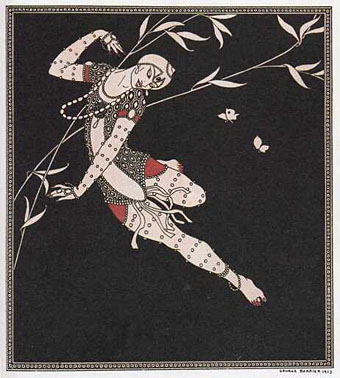

Psyché Rock was the second track on Messe Pour Le Temps Present, an album of music composed in part with Michel Colombier. (It was also released on an EP with three other Henry/Colombier tracks, and later as a single in its own right.) The Messe section of the album was the score for a Maurice Béjart dance piece, a small example of which can be seen here. There’s also this silly dance sequence from French TV featuring stripping meter maids.

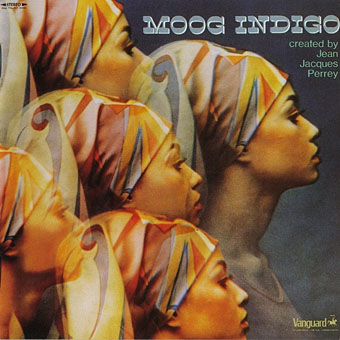

Moog Indigo (1970).

Another French composer, Jean-Jacques Perrey, looked from inner to outer space in 1970 with E.V.A., a track on his Moog Indigo album. This sounds very similar to Psyché Rock, albeit less wild and much more groovy, and may also be an inspiration for the Futurama theme. This train of associations has given E.V.A. a life beyond its album release.

As to Futurama, there’s a mass of clips and themes of differing lengths out there. I’ll mention Fatboy Slim’s remixes only to say that I’ve never been very enamoured of Quentin’s compositions so the less said about him (and them), the better. Les Jerks Électroniques De La Messe Pour Le Temps Présent Et Musiques Concrètes De Pierre Henry Pour Maurice Béjart was available on CD as recently as 2009 in a package which shows some of the equipment used to produce its sounds.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch