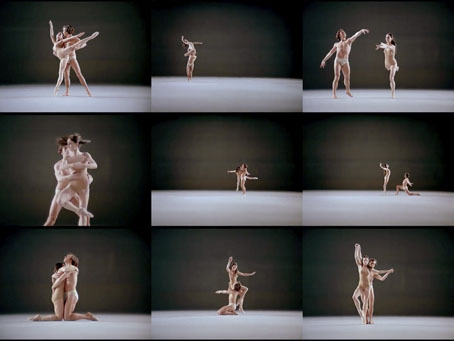

The soul leaves the body. Drawn by intense light, the spirit discovers its twin self, its feminine side…its guide in the beyond. Inspired by the myths of the afterlife, this allegorical dance piece illuminates the soul’s quest by exploring movement and the human body in new and astonishing ways. An evocation of the origins of the world. A hymn to the beauty of the human form. A celebration of movement.

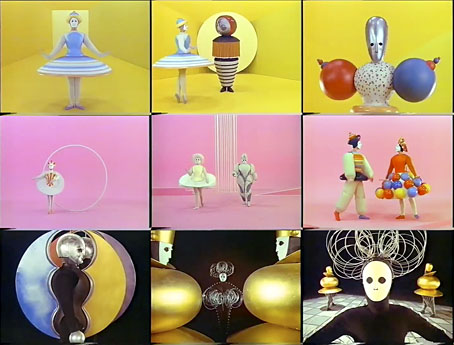

Lodela (1996) was a production for the National Film Board of Canada, and in many ways it acts as a response to (or evolution from) an earlier NFBC film, Norman McLaren’s justly-celebrated Pas de Deux (1968). Both films depict an encounter between two dancers in an abstract black-and-white space; both films also take advantage of their medium to present dance in a manner that would be impossible on a stage. In McLaren’s film the dancers’ movements are multiplied via optical printing, a process that gives their gestures a liquid, hallucinatory grace.

For Lodela Philippe Baylaucq has his dancers (José Navas and Chi Long) situated on an illuminated circle surrounded by the dark, one side of which is shown in negative. He also does some simple things with the camera which are nevertheless strikingly effective and unusual in a dance piece, such as filming the dancers upside down, and attaching the camera to their bodies for dizzying close-ups. Choreographers (and dancers, for that matter) often get agitated if dancers’ bodies aren’t shown in full so this latter piece of direction is very unusual. Watch the film here. Pas de Deux, incidentally, is also on the National Film Board of Canada’s Vimeo channel, and in much better quality than earlier YouTube versions. Watch them together.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Pas de Deux by Norman McLaren

• Norman McLaren