Andreas and Paulo photographed by John Andresen.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Youssef Nabil

• Images of Nijinsky

• The art of Hubert Stowitts, 1892–1953

• John Andresen

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Dance

Andreas and Paulo photographed by John Andresen.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Youssef Nabil

• Images of Nijinsky

• The art of Hubert Stowitts, 1892–1953

• John Andresen

Ballerina boy, Paris 2003.

Youssef Nabil colours his photographs so they look like antique hand-tinted prints. Plenty of striking examples on his site, including portraits of one of my favourite singers, Natacha Atlas.

I have an abiding fascination with the Ballets Russes, Sergei Diaghilev‘s company which electrified the art world from 1909 up to the impressario’s death in 1929. One of the reasons for this—aside from the obvious gay dimension and the extraordinary roster of talent involved—is probably Diaghilev’s success in carrying the Symbolist impulses of the fin de siècle into the age of Modernism without losing any richness or exoticism along the way. Diaghilev’s arts magazine, Mir Iskusstva (1899–1900), was as much a product of fashionable Decadence as The Savoy, and its principles were easily transported into the world of ballet.

I have an abiding fascination with the Ballets Russes, Sergei Diaghilev‘s company which electrified the art world from 1909 up to the impressario’s death in 1929. One of the reasons for this—aside from the obvious gay dimension and the extraordinary roster of talent involved—is probably Diaghilev’s success in carrying the Symbolist impulses of the fin de siècle into the age of Modernism without losing any richness or exoticism along the way. Diaghilev’s arts magazine, Mir Iskusstva (1899–1900), was as much a product of fashionable Decadence as The Savoy, and its principles were easily transported into the world of ballet.

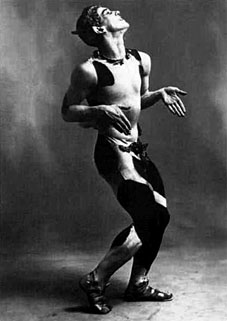

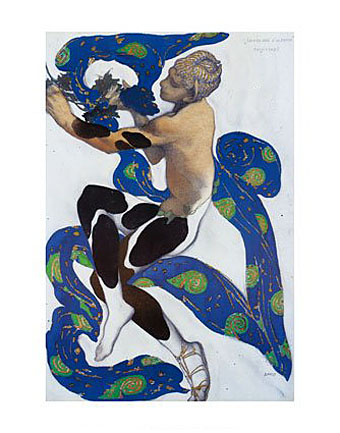

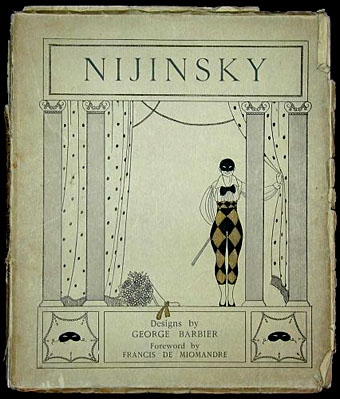

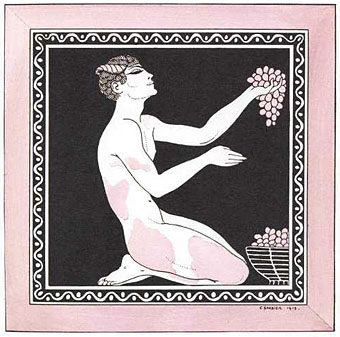

A big subject, then, that’ll no doubt be returned to in later postings. Looking around for images of dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky in his celebrated (and notorious) role in L’Après-midi d’un Faune turned up not only Leon Bakst’s luscious drawing but some marvelous Beardsley-esque pictures by George Barbier (1882–1932). I’d seen some of Barbier’s work before but didn’t realise he’d created a whole book devoted to the dancer. Artists like Bakst, Erté and Barbier show how Aubrey Beardsley’s art might have developed had he not died prematurely in 1898. You can see the full set of book plates here.

Nijinsky as faun by Leon Bakst (1912).

Designs on the Dances of Vaslav Nijinsky (and below) by George Barbier (1913).

L’ Apres-midi d’un Faune.

Narcisse.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Nicholas Kalmakoff, 1873–1955

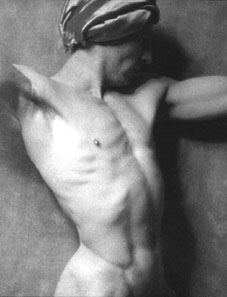

Left: Stowitts photgraphed by Nickolas Muray, 1922.

Hubert Julian Stowitts had a number of careers, including dancer, film actor, painter, designer and metaphysician. As a dancer he worked with Anna Pavlova, who discovered him in California in 1915 and took him on tour around the world. His statuesque figure was used by Rex Ingram for the infernal scenes in The Magician (1926), an adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s rather limp roman-à-clef based on the exploits of Aleister Crowley. The scene with Stowitts as a satyr owed nothing to the book, however, being more inspired by the director’s fondness for the tales of Arthur Machen. Most photos that turn up from this film show Stowitts rather than Paul Wegener who played the sinister alchemist of the title.

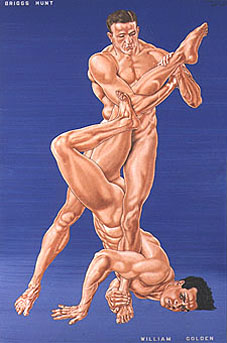

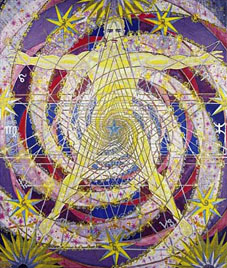

Stowitt’s painting developed in the 1930s and included a series of 55 paintings of nude (male) athletes for the 1936 Olympics (see Ewoud Broeksma’s contemporary equivalents at originalolympics.com). Other paintings depicted dance scenes, costume designs, people encountered during travels in the Far East and, in the 1950s, a series of ten Theosophist pictures entitled The Atomic Age Suite.

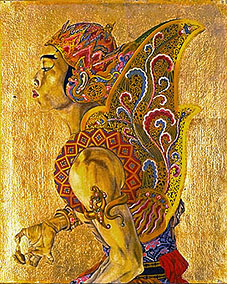

Prince Suwarno in Mahabarata role (1928).

Briggs Hunt and William Golden (1936).

The Crucifixion in Space (1950).

• The Stowitts Museum and Library

• Stowitts at the Queer Arts Resource

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Nicholas Kalmakoff, 1873–1955

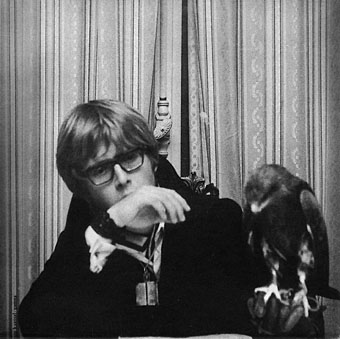

Igor Wakhévitch and feathered friend.

Continuing the Francophile theme, I felt that now was a good time to plumb the mysteries of the enigmatic Igor Wakhévitch. Who? Well… In 20th century music there’s strange and there’s weird and then there’s off-the-wall unclassifiable which is the place where we have to file Igor’s compositions. After half a lifetime spent trawling record shops for unusual music these albums had somehow managed to remain off the radar until a CD reissue set, Donc…, appeared courtesy of Fractal Records and a friend with similarly outré tastes (hi Gav!). The obscurity of these remarkable recordings can’t solely be due to Monsieur Wakhévitch being French; Richard Pinhas, Bernard Szajner and (of course) Magma, have been given enough attention over the years.

So what does this stuff sound like? Thankfully the redoubtable Alan Freeman tackled the problem of describing the albums in Audion (reproduced below), a task I would have found rather daunting. Docteur Faust is probably my favourite, a crazily eclectic and doomy album which lurches from rock freakout to contemporary orchestral/choral to electro-acoustics and back again. Imagine the witch cult from Rosemary’s Baby jamming with Alpha Centauri-era Tangerine Dream while Peter Maxwell Davies and Amon Düül 2 slug it out in the background. The clincher is a great cover by French comic artist Philippe Druillet.

One other notable album that the Donc… collection omits is the 1974 recording of Salvador Dalí’s opera, Être Dieu. Dalí wrote the libretto in 1927 with Federico Garcia Lorca but the piece wasn’t recorded until Wakhévitch provided a score. The result is pretty much the same as Wakhévitch’s other work, with the added bonus of the Surrealist master declaiming and frequently shrieking over the music.

For more information about Donc… and Igor Wakhévitch see the Fractal Records review page.