Guilty Pleasures of Literary Greats.

Drew Friedman rules.

Category: {comics}

Comics

Tygers of Wrath

ImageTexT is an excellent web publication produced by the English Department at the University of Florida whose objective “is to advance the academic study of comic books, comic strips, and animated cartoons”. The subject of the latest edition is “William Blake and Visual Culture” and to this end includes my written and visual account of the Tate Gallery’s William Blake event from February 2001. That evening of song and performance featured Alan Moore and Tim Perkins’ piece about Blake’s life (with my video accompaniment), a work that was later released as the Angel Passage CD. ImageText 3-2 also includes an essay by Roger Whitson, Panelling Parallax: The Fearful Symmetry of William Blake and Alan Moore.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Of Moons and Serpents

• Watchmen

• Alan Moore interview, 1988

Of Moons and Serpents

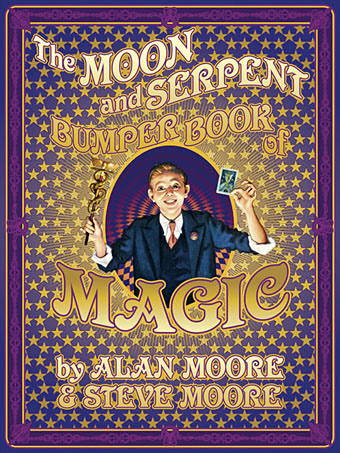

It’s lunar, it’s serpentine, it’s grandly thaumaturgical. Cover design by yours truly.

Via Top Shelf:

Splendid news for boys and girls, and guaranteed salvation for humanity! Messrs. Steve and Alan Moore, current proprietors of the celebrated Moon & Serpent Grand Egyptian Theatre of Marvels (sorcery by appointment since circa 150 AD) are presently engaged in producing a clear and practical grimoire of the occult sciences that offers endless necromantic fun for all the family. Exquisitely illuminated by a host of adepts including Kevin O’Neill, Melinda Gebbie, John Coulthart, José Villarrubia and other stellar talents (to be named shortly), this marvelous and unprecedented tome promises to provide all that the reader could conceivably need in order to commence a fulfilling new career as a diabolist.

Its contents include profusely illustrated instructional essays upon this ancient sect’s theories of magic, notably the key dissertation “Adventures in Thinking” which gives reliable advice as to how entry into the world of magic may be readily achieved. Further to this, a number of “Rainy Day” activity pages present lively and entertaining things-to-do once the magical state has been attained, including such popular pastimes as divination, etheric travel and the conjuring of a colourful multitude of sprits, deities, dead people and infernal entities from the pit, all of whom are sure to become your new best friends.

Also contained within this extravagant compendium of thaumaturgic lore is a history of magic from the last ice-age to the present day, told in a series of easy-to-absorb pictorial biographies of fifty great enchanters and complemented by a variety of picture stories depicting events ranging from the Paleolithic origins of art, magic, language and consciousness to the rib-tickling comedy exploits of Moon & Serpent founder Alexander the False Prophet (“He’s fun, he’s fake, he’s got a talking snake!”).

In addition to these manifold delights, the adventurous reader will also discover a series of helpful travel guides to mind-wrenching alien dimensions that are within comfortable walking distance, as well as profiles of the many quaint local inhabitants that one might bump into at these exotic resorts. A full range of entertainments will be provided, encompassing such diverse novelties and pursuits as a lavishly decorated decadent pulp tale of occult adventure recounted in the serial form, a full set of this sinister and deathless cult’s never-before-seen Tarot cards, a fold-out Kabalistic board game in which the first player to achieve enlightenment wins providing he or she doesn’t make a big deal about it, and even a pop-up Theatre of Marvels that serves as both a Renaissance memory theatre and a handy portable shrine for today’s multi-tasking magician on the move.

Completing this almost unimaginable treasure-trove are a matching pair of lengthy theses revealing the ultimate meaning of both the Moon and the Serpent in a manner that makes transparent the much obscured secret of magic, happiness, sex, creativity and the known Universe, while at the same time explaining why these lunar and ophidian symbols feature so prominently in the order’s peculiar name. (Manufacturer’s disclaimer: this edition does not, however, reveal why the titular cabal of magicians consider themselves to be either grand or Egyptian. Let the buyer beware.)

A colossal and audacious publishing triumph of three hundred and twenty pages, beautifully produced in the finest tradition of educational literature for young people, The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic will transform your lives, your reality, and any spare lead that you happen to have laying around into the purest and most radiant gold.

A 320-Page Super-Deluxe Hardcover, co-written by Alan Moore and Steve Moore, and illustrated by various luminaries from the comic book field.

Cover design by John Coulthart.

A 2009 RELEASE!

ISBN 978-1-60309-001-8

Taxandria, or Raoul Servais meets Paul Delvaux

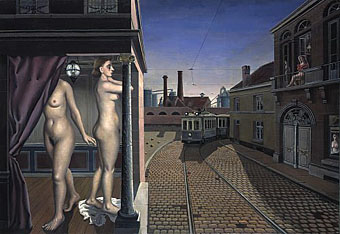

La Rue du Tramway (1938) by Paul Delvaux.

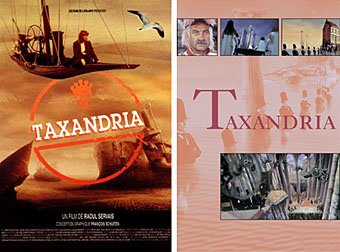

Taxandria (1994) is a feature-length fantasy film by Belgian animator Raoul Servais that’s received little attention outside his native country, possibly because it failed in the marketplace and has been deemed too weird or uncommercial to export. You only have to compare the export version of Harry Kümel’s Malpertuis with his original cut to see how inventive Belgian films are treated by US distributors.

Servais had previously made an acclaimed animated short, Harpya, using a combination of live actors and painted backgrounds. Taxandria elaborates on this process (called Servaisgraphy by its inventor) using settings designed by one of my favourite comic artists François Schuiten, creator (with Benoît Peeters) of Les Cités Obscures. Taxandria intrigues for a third reason, the inspiration of Surrealist master Paul Delvaux whose paintings served as the origin of the project. And it also contains a remarkable detail in the screenplay credit for Alain Robbe-Grillet, a man better known for making Last Year at Marienbad with Alain Resnais, and the kind of fierce intellectual one imagines would usually run a mile from this kind of extravagant whimsy.

Continue reading “Taxandria, or Raoul Servais meets Paul Delvaux”

The persistence of memory

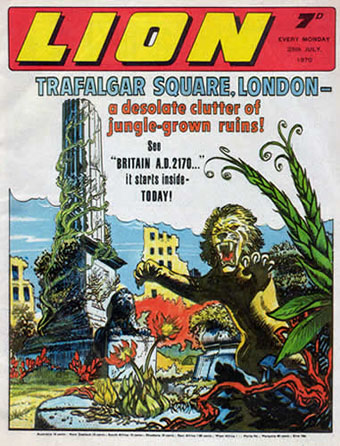

Ballard-for-kids from Lion (1970).

I was never a great hoarder of comics when I was a child, I usually read them then threw them away, so for years I’ve had peculiar half-memories of stories that thrilled me when I was 10-years old but whose titles I’ve invariably forgotten. The web, of course, serves to immediately answer desperately nagging questions such as “Who was the boy in a home-made catsuit climbing all over buildings at night?” (Billy the Cat, and sister Katie), “Which comic did bendable hero Janus Stark appear in?” (Smash and later Valiant), and so on.

British comics nearly always seemed stranger than American ones even though I was a regular reader of Spider-Man and a couple of other Marvel comics. Many of the British adventure titles—all long since expired—were created by artists and writers who drew freely on pulp traditions from the late 19th and early 20th century. Reading through histories of comics such as Lion it’s notable how many of the stories are set in the Victorian era. These tales were invariably hokey and certainly don’t bear much examination now but I can trace later interests back to an early stimulation by these odd strips.

The evil Ezra Creech.

I’m actually surprised to discover that I was a regular reader of Lion, its list of characters is very familiar yet I don’t remember buying a single issue. Lion is significant for being home to one of my favourite strips of the period, the chilling horror/thriller The War of the White Eyes. I’ve yet to meet anyone who remembers reading this which used to be frustrating when I’d pester comic-collecting friends to try and recall which title it appeared in. The story was fairly standard adventure fare from 1972:

The War Of The White Eyes was a US-type fantasy strip which had our heroes, Nick Dexter and Don Redding, trying to thwart the evil megalomaniac, Ezra Creech, who was baying for world domination by inhaling a deadly gas that transformed him into a ‘White-Eyes’, a creature of superhuman strength and ferocity. At first, Creech wanted to destroy our heroes’ home island of Doomcrag and then go on to world domination, but guess who stopped him?

If you live in a place called Doomcrag you’re asking for trouble. I didn’t remember there being a super-villain involved although someone had to be responsible for raining the globes of deadly gas down on the populace.

Creech could turn people into white-eyed zombies under his control. He had superhuman strength as a White Eye. He later developed a ray that allowed him to make things grow, giving him the ability to create monsters.

JMB Chemicals developed a new gas as a mild insecticide. However it proved to have unforeseen side-effects. Men and animals exposed to it were transformed into killers of extraordinary strength and ferocity, recognisable by their white eyes. The first evidence of this came when a few glasses containers of the gas accidentally dropped from the back of a van transporting them through the peaceful English town of Wimbering. Those exposed demonstrated an innate hatred of anyone untainted, and set out to conquer the area and kill “the weaklings”. Even the army proved helpless, with White Eyes ripping apart tanks with their bare hands and throwing them around like toys. Even the White Eyes animals joined in, with contaminated birds attacking troops on the ground. It was only through the bravery and ingenuity of local boys Nick Dexter and Don Redding, and the scientist Timms who had developed the gas in the first place (and also concocted an antidote) that order was restored.

This was very much a horror strip for kids—at least as I remember it—with crazed, white-eyed people and animals going on the rampage, and the ever-present danger that our heroes could be infected themselves. The strip taught me very early on that the simplest way to make someone look evil was to blank out their pupils, something I spent the rest of the decade doing in drawing after drawing.

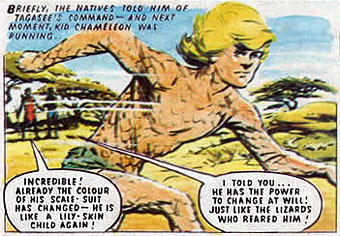

Kid Chameleon takes off.

Another favourite was Kid Chameleon (not to be confused with a later computer game character) whose adventures appeared in my favourite comic of the time, Cor!!:

Stranded in the Kalahari Desert by a plane crash, a British boy is raised by lizards as a feral child, and weaves himself a skin-tight suit of transparent lizard scales which covers his entire body except the top of his head (to avoid the appearance of complete nudity, he also wears a pair of flesh-coloured briefs underneath). Only one strip shows how the suit comes off. It consists of two pieces: a top that opens at the front, and leggings. The suit allows him to camouflage himself like a chameleon by making the scales change colour, although how he does it is never explained.

Yes, I was eagerly reading about a near-naked boy when I was 10; make of that what you will. Kid Chameleon spent two years tracking down the man who caused the plane crash before returning to the desert and the company of the lizards. This strikes me as a very Burroughs-esque idea now, there being plenty of lizard boys and skin suits in Burroughs’ early novels such as The Soft Machine and The Ticket that Exploded. In many ways, Kid Chameleon isn’t far removed from the various incarnations of the Wild Boys—resourceful, shape-shifting and always a loner. By a curious coincidence Burroughs was in London writing Port of Saints, the sequel to The Wild Boys, at the time Cor!! was publishing Kid Chameleon.

There aren’t any pages online from The War of the White Eyes; perhaps that’s for the best, it would only shatter my vague memories even further. However, you can see a couple of pages from Kid Chameleon here, written by Scott Goodall. The strip was drawn by Joe Colquhoun, later the artist on Charlie’s War by Pat Mills.