Aklo: A Journal of the Fantastic, Spring 1988 edition, edited by Mark Valentine & Roger Dobson. Illustration by Alan Hunter.

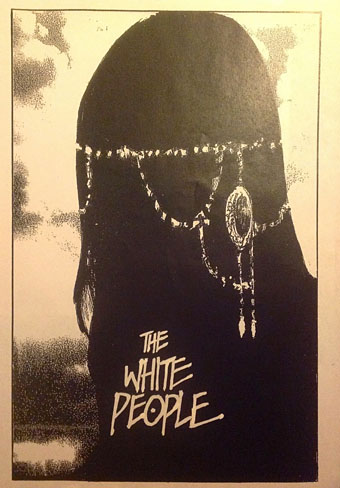

1: The White People

The White People by Arthur Machen was written in 1899 but not published until it appeared in Horlick’s Magazine, January 1904. The magazine, which ran for just over a year, was edited by Machen’s Golden Dawn colleague AE Waite which no doubt explains the unlikely venue. HP Lovecraft enthused about the story in Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927):

Less famous and less complex in plot than The Great God Pan, but definitely finer in atmosphere and general artistic value, is the curious and dimly disquieting chronicle called The White People, whose central portion purports to be the diary or notes of a little girl whose nurse has introduced her to some of the forbidden magic and soul-blasting traditions of the noxious witch-cult — the cult whose whispered lore was handed down long lines of peasantry throughout Western Europe, and whose members sometimes stole forth at night, one by one, to meet in black woods and lonely places for the revolting orgies of the Witches’ Sabbath. Mr. Machen’s narrative, a triumph of skilful selectiveness and restraint, accumulates enormous power as it flows on in a stream of innocent childish prattle, introducing allusions to strange “nymphs,” “Dols,” “voolas,” “white, green, and scarlet ceremonies,” “Aklo letters,” “Chian language,” “Mao games,” and the like. The rites learned by the nurse from her witch grandmother are taught to the child by the time she is three years old, and her artless accounts of the dangerous secret revelations possess a lurking terror generously mixed with pathos. Evil charms well known to anthropologists are described with juvenile naiveté, and finally there comes a winter afternoon journey into the old Welsh hills, performed under an imaginative spell which lends to the wild scenery an added weirdness, strangeness, and suggestion of grotesque sentience. The details of this journey are given with marvellous vividness, and form to the keen critic a masterpiece of fantastic writing, with almost unlimited power in the intimation of potent hideousness and cosmic aberration.

Lovecraft borrowed Machen’s naive narrator a year later for The Dunwich Horror: Wilbur Whateley’s diary is written “by a child of three-and-a-half who looked like a lad of twelve or thirteen”, and makes reference to “Aklo”, “the Dho formula” and “the Voorish sign”. (The journal in The White People refers to “a wicked voorish dome”.)

Lovecraft wasn’t alone in being impressed by the story, it’s long been regarded as Machen’s greatest piece of short fiction with good reason:

…it remains the purest and most powerful expression of what Jack Sullivan has called the “transcendental” or “visionary” supernatural tradition. Most other tales in that tradition, Blackwood’s The Wendigo, EF Benson’s The Man Who Went Too Far, and Machen’s own The Great God Pan, merely describe encounters with the dark primeval forces that reign beyond the edge of civilisation; The White People seems an actual product of such an encounter, an authentic pagan artefact…

TED Klein, The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (1986)

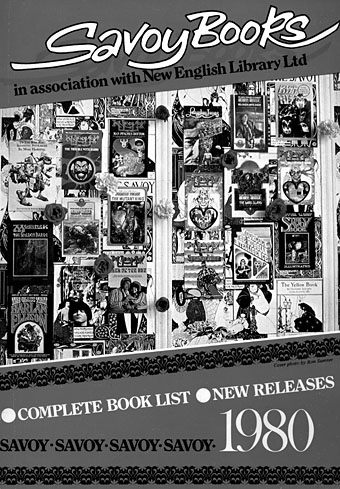

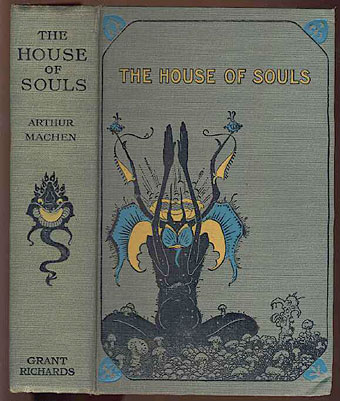

2: The House of Souls

The House of Souls (1906). Cover illustrations by Sidney Sime.

The story was first collected in The House of Souls in 1906, a book that features a splendidly weird cover illustration by Sidney Sime. Inside there’s some of Machen’s finest supernatural writing including The Great God Pan, The Inmost Light and The Three Imposters. Also included is A Fragment of Life, a visionary piece that begins as a domestic drama but by the end has almost intersected with The White People.

And by coincidence (or is it?), I’ve just noticed that Tartarus Press are publishing a facsimile edition of the 1906 volume later this month.

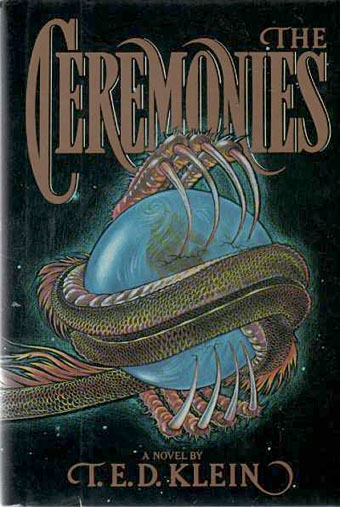

3: The Ceremonies

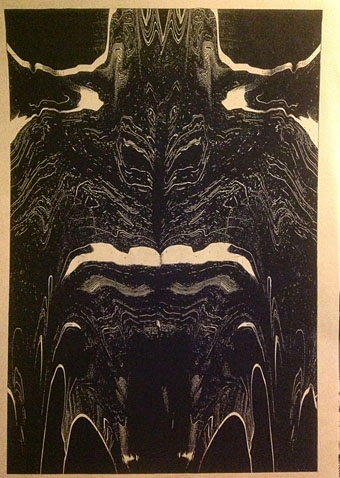

The Ceremonies (1984). Illustration by David Palladini.

TED Klein’s debut novel is also his only novel to date. Klein was editor of The Twilight Zone Magazine at this time, and he used the publication’s popularity to promote the weird fiction of the past; writers like Machen and Algernon Blackwood weren’t as visible in the mid-80s as they are today. The Ceremonies was expanded from a 1972 novella, The Events at Poroth Farm, and borrows much from The White People: the ceremonies of the title refers to those in the story, and the story itself—which a character is instructed to read by moonlight—is described as a key to occult mysteries. There’s a lot about the novel to recommend—Klein’s prose for a start—but I felt it could have been much weirder than it was. The book reads like a typical King/Straub narrative that’s aiming for more without quite getting there, and placing something as unique as Machen’s story at its heart only makes its eventual shortcomings all the more apparent.

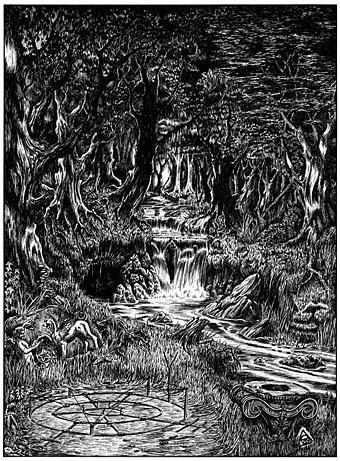

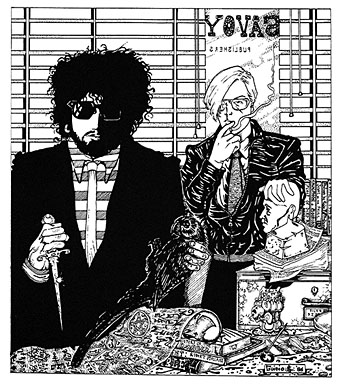

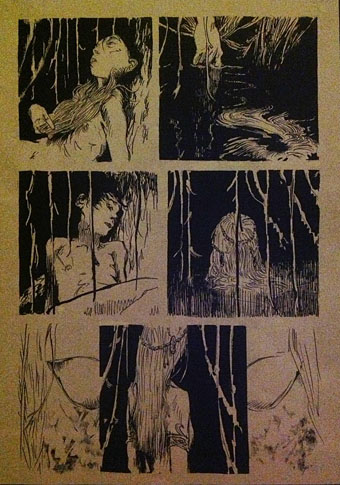

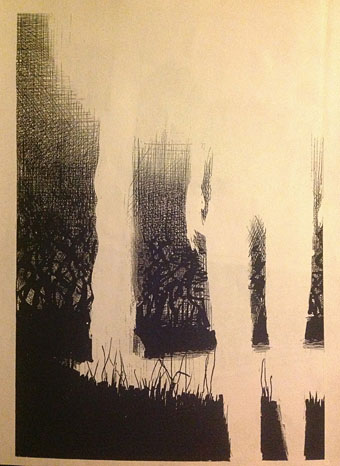

4: A drawing

The White People (1990) by John Coulthart.

And speaking of aiming for more without quite getting there, my drawing from 1990. This was going to be one of a series based on Machen’s story but I ran out of steam, feeling that the usual approach of drawing separate scenes wasn’t going to deliver the essence of the piece. If I tried this today I’d probably go for a more surreal approach the way Sätty did with Poe.

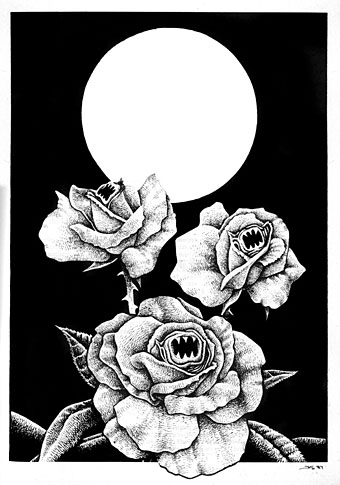

5: Roses

The Singing Roses (1987) by Jeffrey Salmon. From Dagon magazine no. 18/19, July–October, 1987.

“And what is sin?” said Cotgrave.

“I think I must reply to your question by another. What would your feelings be, seriously, if your cat or your dog began to talk to you, and to dispute with you in human accents? You would be overwhelmed with horror. I am sure of it. And if the roses in your garden sang a weird song, you would go mad. And suppose the stones in the road began to swell and grow before your eyes, and if the pebble that you noticed at night had shot out stony blossoms in the morning?

The White People

*

Sweet tortures fly on mystery wings / Pure evil is when flowers sing / My heart / My heart is a rose

Love’s Secret Domain (1991) by Coil

6: Ghost Box

Ouroborindra (2005) by Eric Zann. Design by Julian House.

Track 4: Dôls

Track 6: Voolas

The Owl’s Map (2006) by Belbury Poly. Design by Julian House.

Track 11: Scarlet Ceremony

Among the sleeve notes there’s this:

And the noise and the singing would go on and on for a long time, and the people who were in a ring swayed a little to and fro; and the song was in an old, old language that nobody knows now, and the tune was queer.

Arthur Machen, The White People

7: The White People by Ibrahim R. Ineke

A very impressive comic-strip adaptation, the first of its kind, as far as I’m aware. See the full run of pages here. (And thanks to Ibrahim for getting in touch!)

For those who can’t afford a limited edition from Tartarus Press, Machen’s story may currently be found in Penguin’s The White People and Other Weird Stories. The perfect thing now the nights are drawing in.

Update: See also The Forbidden Forest, a short animation based on the story. (Thanks, Richard!)

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Bowmen by Arthur Machen

• Rex Ingram’s The Magician

• The Great God Pan