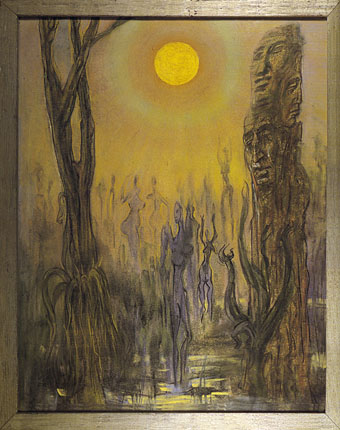

Cthulhu Cultus: The Sun is Sick (no date) by Austin Osman Spare.

I’ve been telling people about this drawing for years but I’ve not posted it here before. Spare produced this piece after Kenneth Grant gave him some of HP Lovecraft’s stories to read. I’ve never seen it dated but it’s probably from the mid-50s when Kenneth and Steffi Grant were corresponding with Spare and commissioning new artworks. What’s notable for me is that this is probably the first Lovecraft-derived drawing that wasn’t either a magazine or book illustration, or something done for one of the horror fanzines.

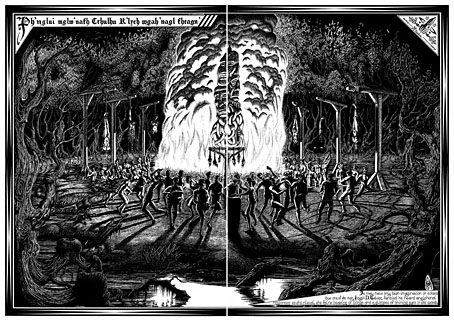

The Call of Cthulhu (1987) by John Coulthart.

Lovecraft aficionados have never seemed aware of Spare’s drawing since Lovecraft studies tended until very recently to remain fixed on popular media and the often parochial world of genre fandom. When I came to draw the swamp scene for The Call of Cthulhu in 1987 I borrowed the faces from Spare’s pillar for the column in the centre of the picture.

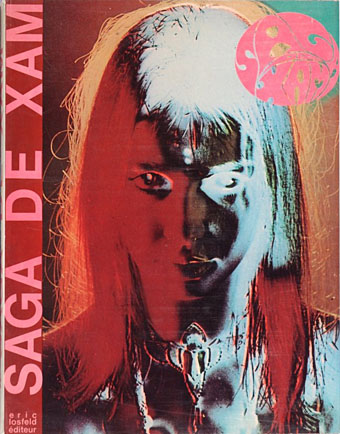

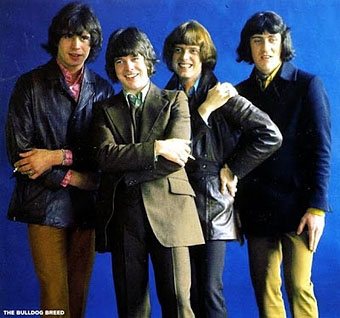

Bulldog Breed.

While we’re on the subject, and in the spirit of showing how all the obsessions here connect in one way or another, Phil Baker’s excellent biography of Austin Spare notes a surprising reference to the artist that predates Man, Myth and Magic via the psychedelic music scene. Bulldog Breed were a short-lived London group, one of many being promoted by the Deram label in the late 1960s. The group’s one-and-only album, Made In England, was released in 1969. The cover art is dreadful but the final song is a number entitled Austin Osmanspare [sic], a paean to the artist that turns AOS into a typical character from British psychedelia: an eccentric, oddly named, Victorian type with a sinister and mysterious glamour. According to Baker one of the band members had an aunt who knew Spare. It’s not a bad song, and the choice of magus gave them an edge over the Beatles who went for the more obvious Aleister Crowley. “They said he was before his time…”

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Dreaming Out of Space: Kenneth Grant on HP Lovecraft

• MMM in IT

• Intertextuality

• Abrahadabra

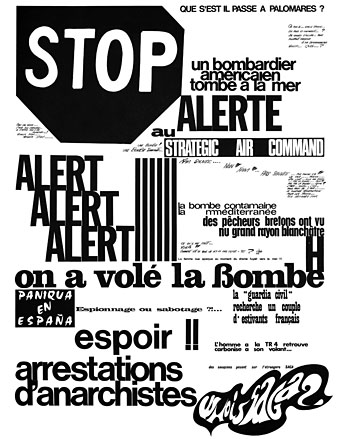

• The Occult Explosion

• Murmur Become Ceaseless and Myriad

• Kenneth Grant, 1924–2011

• New Austin Spare grimoires

• Austin Spare absinthe

• Austin Spare’s Behind the Veil

• Austin Osman Spare