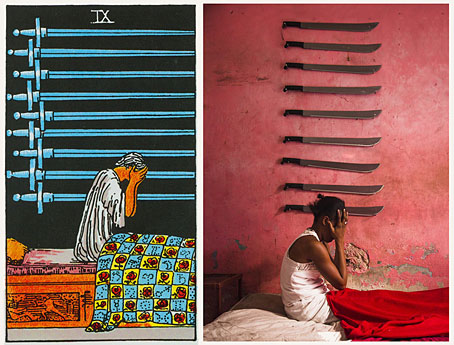

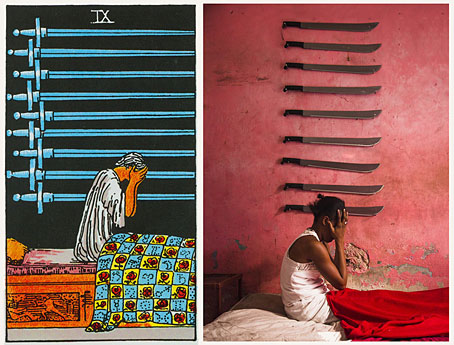

The Nine of Swords by Pamela Colman Smith, and the same card from The Ghetto Tarot, a Haitian deck created by photographer Alice Smits and Haitian art group Atis Rezistans.

Almost four months after the murders in Paris, Charlie Hebdo continues to be problematic, to use a common epithet. The “p” word occurs with such frequency in current discussions about offence—and those discussions so often seem like a secular version of old religious arguments, with Manichean forces pitted against each other, and the same schisms, heresies and witch hunts—that I’ve taken to translating “problematic” as “sinful”. Charlie Hebdo is nothing if not a heretical text even if many of those pronouncing on its heresies have never read a copy. Back in January I was confident that we’d be seeing a great deal of equivocation (if not outright victim-blaming) when people began to look closely at the magazine, or at least read hasty appraisals of its contents. You didn’t have to be a psychic to predict any of this because the equivocations are merely the current manifestation of a familiar syndrome. This week’s authorial objections about PEN America honouring Charlie Hebdo have led to a reiteration of the grumblings we heard in January: “Yes, of course, we condemn the violence but…” But, what? “But, it’s a sinful publication…”(This piece by one of the PEN objectors in the LRB is typical.) Publication liberties, which in the UK are more constrained than in the US, are apparently best championed for the virtuous (the responsible, the respectful, etc), not the sinful. In 1963 “Yes, but…” equivocations about freedom of speech were being deployed in the letters page of the Times Literary Supplement with worthies such as Victor Gollancz and Edith Sitwell wondering why it was necessary to defend a deplorable book like The Naked Lunch; in 1992 I sat in a courtroom watching a judge make similar comments when grudgingly overturning an obscenity ruling against David Britton’s Lord Horror novel. The same judge then upheld the obscenity charge against Britton & Guidio’s Meng & Ecker comic which he regarded as trashier fare, “luridly bound” and containing “pictures that will be repulsive to right-thinking people”.

So much for old arguments. Jodie Ginsberg at Index on Censorship goes into some detail about the PEN kerfuffle in a piece entitled “I believe in free expression, but…”; Justin EH Smith for Harper’s says:

I heard from [friends and equals] countless variations on the banality that “violence is always wrong.” How did I know that this judgment, though perfectly true in itself, was only a banality, the expression of a sentiment that had little to do with pacifism? By the clockwork predictability of the “but” that always followed.”

Kenan Malik, who writes a great deal about these issues (his new book is The Quest for a Moral Compass: A Global History of Ethics) posted a statement from Jo Glanville from English PEN, and a lengthy piece by Leigh Phillips. This affair will rumble on.

• More sinful material: Samuel R. Delany’s Hogg is a novel so transgressive/offensive that it took 26 years to find a publisher. You seldom see any mention of the book when Delany’s work is being discussed, especially in prudish SF circles, but Dennis Cooper’s blog ran a retrospective feature about it this week. Caveat lector. Related: Stories for Chip: A Tribute to Samuel R. Delany is looking for crowdfunding.

• “[Judy] Oppenheimer relates that Jackson kept a library of over two hundred books on witchcraft, and her interest in the subject was not purely academic.” Martyn Wendell Jones on Shirley Jackson.

• The Satyr and Other Tales, a collection by Stephen J. Clark, the title story of which is “inspired by the life and ethos of sorcerer and artist Austin Osman Spare”.

• Mixes of the week: Bacchus Beltane 2: The Mists of Avalon by The Ephemeral Man, and The Ivy-Strangled Path Vol. VI by David Colohan.

• Boy and his SIR: BDSM and the Queer Family, a photo series by Kevin Warth, and Xteriors II, a photo series by Desiree Dolron.

• The Quest for Stenbock: David Tibet talks to Strange Flowers about his obsession with the eccentric Count.

• Dark Star: HR Giger’s World is a documentary about the artist by Belinda Sallin.

• 1 in 3 Impressions, a free EP of Moog music by M. Geddes Gengras.

• The rise and fall of the codpiece

• Blade Runner Reality

• Some Weird Sin (1977) by Iggy Pop | Sin In My Heart (1981) by Siouxsie and The Banshees | It’s A Sin (1987) by Pet Shop Boys