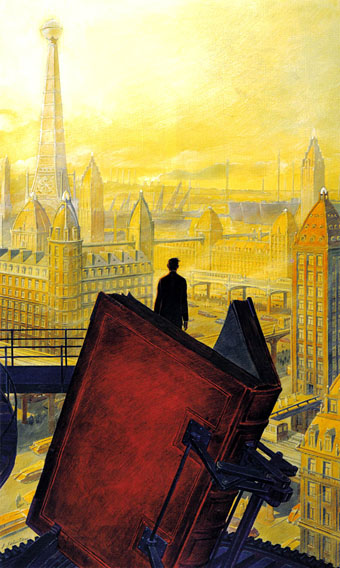

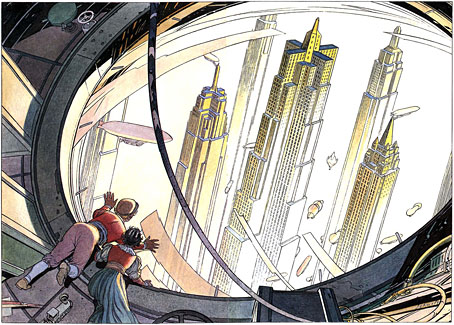

Ferdinand and Hella look down on the skyscrapers of Brüsel.

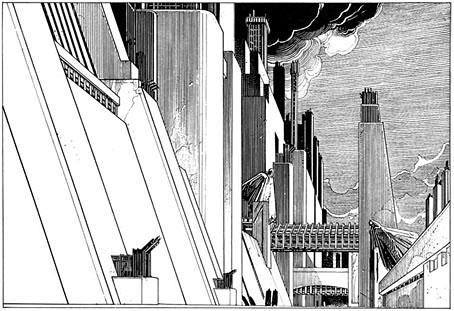

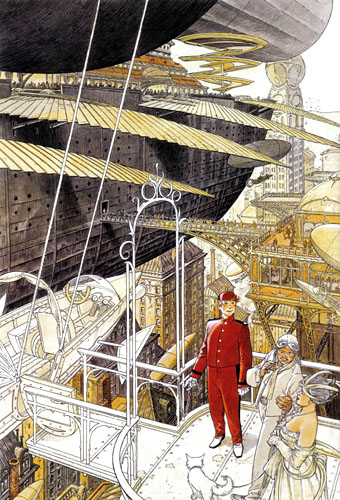

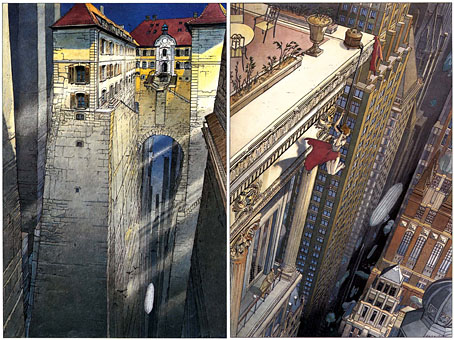

La route d’Armilia (1988) by François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters is the next substantial story in the Cités Obscures series after La Tour; there was also a book about transportation in the Obscure World, L’Encyclopédie des transports présents et à venir, published the same year. La route d’Armilia is the book where Schuiten and Peeters’ Jules Verne influence comes to the fore, with the story of a young boy whose name is derived from Verne characters, Ferdinand Robur Hatteras, undertaking an airship journey to Armilia at the Obscure World’s northern pole. As with the earlier L’archivist, this is mainly an excuse for Schuiten to demonstrate his prodigious architectural invention and draughtsmanship, although the story this time is more of a piece. The journey takes us from the city of Mylos—a dismal place of factories, chimneys and smoke, like one of the polluted cities of the early Industrial Revolution—over the cities of Porrentruy, Mukha, Brüsel, Bayreuth, Calvani, Genova and København. Each city is substantially different from the last, and one of the pleasures is seeing what the next stop along the way will be like.

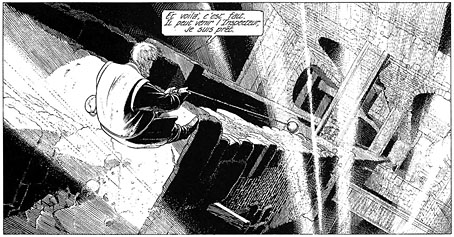

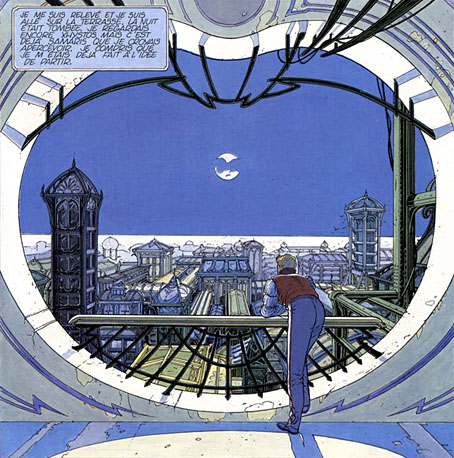

left: the airship passes through the canyon streets of Porrentruy; right: in Brüsel a woman hangs perilously from a ledge. Acrobatics or accident, we never discover which.