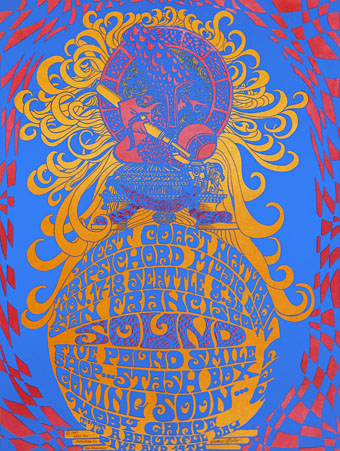

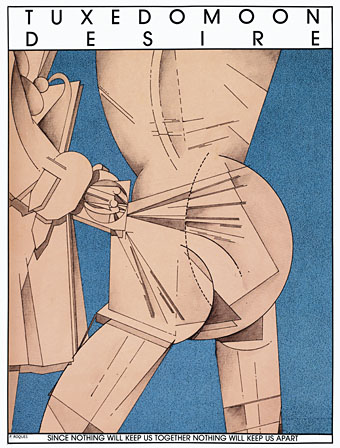

UK poster insert by Patrick Roques for Desire (1981).

Yes, more Tuxedomoon: there’s a lot to explore. It’s always a pleasure when something that you enjoy one medium connects to things that interest you elsewhere. From the outset Tuxedomoon have had more than their share of connections to gay culture—to writers especially—but it’s more of an ongoing conversation than any kind of proselytising concern. This post teases out those connections some of which I hadn’t spotted myself until I started delving deeper.

The Angels of Light: Not the Michael Gira group but an earlier band of musicians and performers in San Francisco in the early 1970s. The Angels of Light formed out of performance troupe The Cockettes following a split between those who wanted to charge admission for their shows, and those who wanted to keep things free to all. Among the troupe there was Steven Brown, soon to be a founding member of Tuxedomoon:

The group began as an offshoot of The Angels of Light, ‘a “family” of dedicated artists who sang, danced, painted and sewed for the Free Theater’, says Steve Brown. ‘I was lucky to be part of the Angels—I fell for a bearded transvestite in the show and moved in with him at the Angels’ commune. Gay or bi men and women who were themselves works of art, extravagant in dress and behaviour, disciples of Artaud and Wilde and Julian Beck [of the Living Theater] … we lived together in a big Victorian house … pooled all our disability cheques each month, ate communally … and used the rest of the funds to produce lavish theatrical productions—never charging a dime to the public. This is what theatre was meant to be: a Dionysian rite of lights and music and chaos and Eros.’

Rip it Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984 by Simon Reynolds

(Special Treatment For The) Family Man (1979): A sombre commentary from the Scream With A View EP on the trial of Dan White, the assassin of Harvey Milk and George Moscone. White’s “special treatment” in court led to a conviction for manslaughter which in turn resulted in San Francisco’s White Night riots in May, 1979.

James Whale (1980): An instrumental on the first Tuxedomoon album, Half-Mute, all sinister electronics and tolling bells as befits a piece named after a director of horror films. Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935) is not only the best of the Universal horror series, it’s also commonly regarded as a subversive examination of marriage and the creation of life from a gay perspective. (Whale’s friends and partner disagreed, however.)

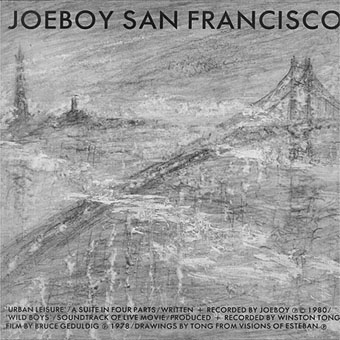

Cover art by Winston Tong.

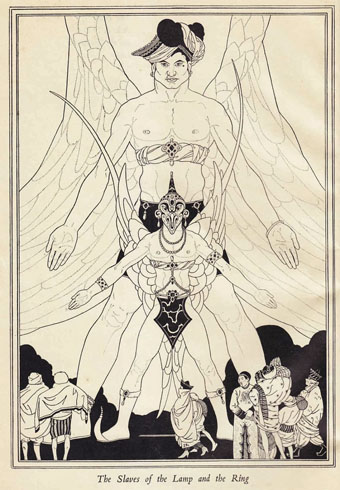

Joeboy San Francisco (1981): The Joeboy name was lifted from a piece of San Francisco graffiti to become a name for Tuxedomoon’s DIY philosophy. It’s also a record label name, the name of an early single, and a side project of the group which in 1981 produced Joeboy In Rotterdam / Joeboy San Francisco. The SF side features a collage piece by Winston Tong based on The Wild Boys by William Burroughs, a key inspiration for the band which first surfaces here.

In one piece, the band cites its influences as: “burroughs, bowie, camus, cage, eno, moroder”. Can you say what you admired or drew on vis-à-vis these artists?

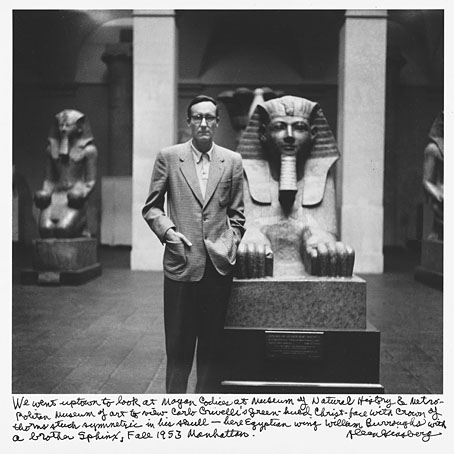

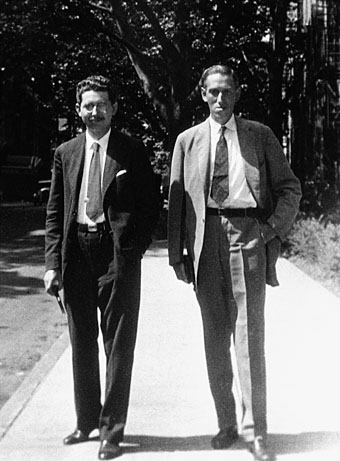

William S. Burroughs — ideas concerning use of media — tapes, projections, his radical anti-control politic in general as well as his outspoken gayness. Early on we duplicated on stage one of his early experiments projecting films of faces onto faces.