An eBay auction. All proceeds, after costs, will benefit Arthur Magazine.

“What else can I say? William Burroughs & his Gilded Cobra…. it’s actually my cobra ….”

Ira Cohen.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

William Burroughs

An eBay auction. All proceeds, after costs, will benefit Arthur Magazine.

“What else can I say? William Burroughs & his Gilded Cobra…. it’s actually my cobra ….”

Ira Cohen.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda

The Digger issue, August 1968.

Here’s something of major importance, The Realist Archive Project. Four complete issues online so far, with a promise of all 146 issues to be uploaded eventually. The Realist started out as a satirical magazine in the late Fifties and moved into the slipstream of the counter-culture as the Sixties progressed. Editor Paul Krassner is introduced in the RE/Search Pranks (1987) book thus:

Paul Krassner is famous for doing The Realist (1958-1974; now revived), described by OUI magazine as “the most satirical and irreverent journal to appear in America since the days of HL Mencken.” The Realist published explicit photos, outrageous cartoons, vicious satire, and extreme paranoid conspiracy theories on topics ranging from the Kennedy assassinations to Jonestown. When Mike Wallace asked him on a 60 Minutes interview about the difference between the underground press and mainstream media, he told him that Spiro Agnew was an anagram for Grow A Penis, adding, “The difference is that I could print that in the Realist, but it’ll be edited out of this program.” That prediction came true. Harry Reasoner said of Krassner that he “not only attacks establishment values; he attacks decency in general.”

During his lifetime of weird experiences and friendships with notables like Lenny Bruce and Timothy Leary, Krassner claims (among other things) to have taken LSD when he testified at the Chicago 8 trial, on the Johnny Carson show, with Groucho Marx, and with Squeaky Fromme and Sandra Good. In 1977 he became publisher of Hustler magazine for six months.

I first encountered the Realist from mentions in Robert Anton Wilson’s books (RAW was one of its writers) but, unlike UK undergrounds which often turned up secondhand, there was no way to ever see a copy over here. Hence the value of this archive. If you want an idea of Krassner’s outrageousness—which makes much of the political sniping of Private Eye seem very tame indeed—look no further than the May 1967 issue with its lead story describing Lyndon B Johnson fucking the dead John F Kennedy’s neck wound shortly before his being sworn in as president. And in the same issue there’s the notorious cartoon spread by Wally Wood depicting a host of Disney characters doing all the things that recently-deceased Uncle Walt wouldn’t allow them to do in the cartoons. That drawing was so scurrilous that it’s generally supposed Disney preferred not to sue for fear of giving it greater publicity.

The issue edited by the anarchist Diggers was altogether more serious, and the list of names involved shows a lineage connecting the Beats to the hippies:

Memo to the Reader

When Time magazine decided to do a cover story on the hippies last year, a cable to their San Francisco bureau instructed researchers to “go at the description and delineation of the subculture as if you were studying the Samoans or the Trobriand Islanders.”

Thus were they supposed to remain—a frozen fad for posterity.

But a few months ago, police rioted on Haight St. Next day, at a town hall meeting in the Straight Theater, the spectrum of reaction ranged from “Let’s have another be-in” to “We gotta get guns!” A compromise was reached: bottles painted Love were thrown at the cops.

And yet, the question remains—What is being defended?

This issue of the Realist, therefore, has been created entirely by The Diggers, in an attempt to convey the flavor and feeling-tone of a revolutionary community.

An inadequate list of the brothers and sisters whose work is represented in this document:

Antonin Artaud, Richard Avedon, Billy Batman, Peter Berg, Wally Berman, Richard Brautigan, Bryden, William Burroughs, Martin Carey, Neil Cassidy, Fidel Castro, Don Cochran, Peter Cohon, Gregory Corso, Dangerfield, Kirby Doyle, Bill Fritsch, Allen Ginsberg, Emmett Grogan, Dave Haselwood, George Hermes, Linn House, Lenore Kandel, Billy Landout, Norman Mailer, Don Martin, Michael McClure, George Metesky, George Montana, Malcolm X, Natural Suzanne, Huey Newton, Pam Parker, Rose-a-Lee, David Simpson, Gary Snyder, Ron Thelin, Rip Torn, Time Inc., Lew Welch, Thomas Weir, Gerard Winstanley, and Anonymous.

The contents herein are not copyrighted. Anyone may reprint anything without permission. Additional copies are available at the rate of 5 for $1. The Diggers have been given 40,000 copies to spread their word: free.

Many of those writers are no longer around but happily Paul Krassner is and he’s been writing regularly for The Huffington Post, the Arthur magazine weblog and other sites.

Via Boing Boing.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Ginsberg’s Howl and the view from the street

• Simplicissimus

• Revenant volumes: Bob Haberfield, New Worlds and others

• Underground history

• Wallace Burman and Semina

• Robert Anton Wilson, 1932–2007

• Barney Bubbles: artist and designer

• 100 Years of Magazine Covers

• Oz magazine, 1967-73

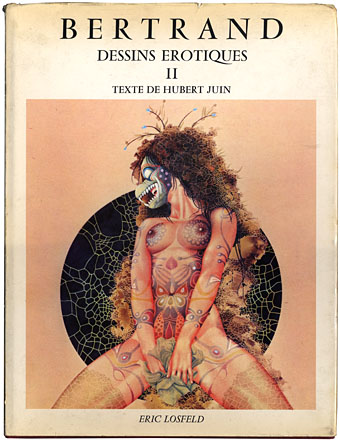

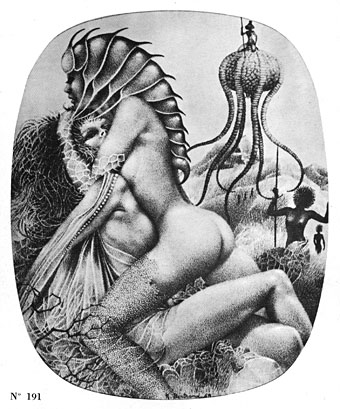

The first question has to be “Bertrand who?” but you won’t receive an answer here since information is scarce (see below). Bertrand’s erotic surrealism first appeared in the late Sixties, going by the dates in collections of his work. Some of his paintings and drawings crept into the underground mags of the period then turned up in odd places throughout the Seventies. The first I saw of any Bertrand art was on the cover of the pre-Savoy publication, Wordworks #6, and a music paper ad for the Chrome 12″, Inworlds.

French porn publisher Eric Losfeld produced a couple of large, limited edition collections of Bertrand’s work in the early Seventies. All the drawings reproduced here are from the battered 1971 volume shown above. If it seems surprising that these haven’t been reprinted it may be that Bertrand’s concerns are too weird or simply too unpleasant for contemporary tastes. Many of his ink drawings, and some of his paintings, seem to have begun life as decalcomania splotches, a Surrealist technique invented by Oscar Dominguez as a means of injecting chance into the creative process. Decalcomania produces random patterns which the artist then elaborates upon. Max Ernst’s famous Europe After the Rain, and a number of his other paintings from the 1940s, began life as a field of vaguely organic marks created by pressing thickly applied paint to the canvas with a sheet of glass or paper. Bertrand used ink stains in a similar way, with the result that most of his doe-eyed female figures (and his figures are nearly always women) are fringed by leafy or fungal growths. Many of his scenes are a kind of lesbian equivalent of the human/alien entanglements one finds in William Burroughs’ more elaborate flights of fancy. If his women aren’t being absorbed into some organic mass, they’re often being subject to investigation (even impalement) by spikes or claws, and here we perhaps find the reason his work remains out of print. Feminists then and now would have taken a dim view of Bertrand’s more violent works; even if Taschen did produce a Bertrand collection, it’s unlikely that many of the more grotesque pictures would be included.

All the pictures in the Losfeld books were produced in a short period from 1967–69. What happened to Bertrand afterwards remains a mystery. Did he decide to do pursue a different, more commercial direction? Is he still alive? The books offer no clue but maybe someone out there has the answer.

Update: Nathalie discovers that the artist in question is Raymond Bertrand, and more of his work can be seen here.

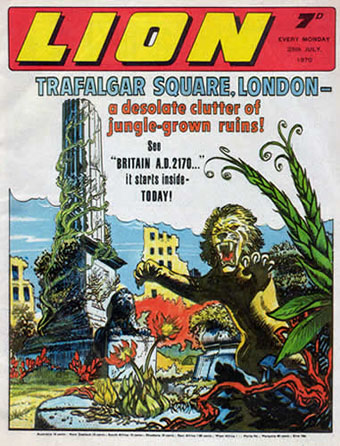

Ballard-for-kids from Lion (1970).

I was never a great hoarder of comics when I was a child, I usually read them then threw them away, so for years I’ve had peculiar half-memories of stories that thrilled me when I was 10-years old but whose titles I’ve invariably forgotten. The web, of course, serves to immediately answer desperately nagging questions such as “Who was the boy in a home-made catsuit climbing all over buildings at night?” (Billy the Cat, and sister Katie), “Which comic did bendable hero Janus Stark appear in?” (Smash and later Valiant), and so on.

British comics nearly always seemed stranger than American ones even though I was a regular reader of Spider-Man and a couple of other Marvel comics. Many of the British adventure titles—all long since expired—were created by artists and writers who drew freely on pulp traditions from the late 19th and early 20th century. Reading through histories of comics such as Lion it’s notable how many of the stories are set in the Victorian era. These tales were invariably hokey and certainly don’t bear much examination now but I can trace later interests back to an early stimulation by these odd strips.

The evil Ezra Creech.

I’m actually surprised to discover that I was a regular reader of Lion, its list of characters is very familiar yet I don’t remember buying a single issue. Lion is significant for being home to one of my favourite strips of the period, the chilling horror/thriller The War of the White Eyes. I’ve yet to meet anyone who remembers reading this which used to be frustrating when I’d pester comic-collecting friends to try and recall which title it appeared in. The story was fairly standard adventure fare from 1972:

The War Of The White Eyes was a US-type fantasy strip which had our heroes, Nick Dexter and Don Redding, trying to thwart the evil megalomaniac, Ezra Creech, who was baying for world domination by inhaling a deadly gas that transformed him into a ‘White-Eyes’, a creature of superhuman strength and ferocity. At first, Creech wanted to destroy our heroes’ home island of Doomcrag and then go on to world domination, but guess who stopped him?

If you live in a place called Doomcrag you’re asking for trouble. I didn’t remember there being a super-villain involved although someone had to be responsible for raining the globes of deadly gas down on the populace.

Creech could turn people into white-eyed zombies under his control. He had superhuman strength as a White Eye. He later developed a ray that allowed him to make things grow, giving him the ability to create monsters.

JMB Chemicals developed a new gas as a mild insecticide. However it proved to have unforeseen side-effects. Men and animals exposed to it were transformed into killers of extraordinary strength and ferocity, recognisable by their white eyes. The first evidence of this came when a few glasses containers of the gas accidentally dropped from the back of a van transporting them through the peaceful English town of Wimbering. Those exposed demonstrated an innate hatred of anyone untainted, and set out to conquer the area and kill “the weaklings”. Even the army proved helpless, with White Eyes ripping apart tanks with their bare hands and throwing them around like toys. Even the White Eyes animals joined in, with contaminated birds attacking troops on the ground. It was only through the bravery and ingenuity of local boys Nick Dexter and Don Redding, and the scientist Timms who had developed the gas in the first place (and also concocted an antidote) that order was restored.

This was very much a horror strip for kids—at least as I remember it—with crazed, white-eyed people and animals going on the rampage, and the ever-present danger that our heroes could be infected themselves. The strip taught me very early on that the simplest way to make someone look evil was to blank out their pupils, something I spent the rest of the decade doing in drawing after drawing.

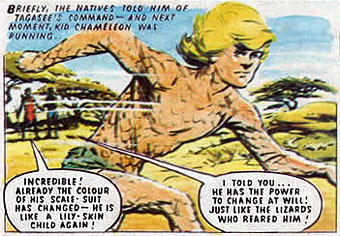

Kid Chameleon takes off.

Another favourite was Kid Chameleon (not to be confused with a later computer game character) whose adventures appeared in my favourite comic of the time, Cor!!:

Stranded in the Kalahari Desert by a plane crash, a British boy is raised by lizards as a feral child, and weaves himself a skin-tight suit of transparent lizard scales which covers his entire body except the top of his head (to avoid the appearance of complete nudity, he also wears a pair of flesh-coloured briefs underneath). Only one strip shows how the suit comes off. It consists of two pieces: a top that opens at the front, and leggings. The suit allows him to camouflage himself like a chameleon by making the scales change colour, although how he does it is never explained.

Yes, I was eagerly reading about a near-naked boy when I was 10; make of that what you will. Kid Chameleon spent two years tracking down the man who caused the plane crash before returning to the desert and the company of the lizards. This strikes me as a very Burroughs-esque idea now, there being plenty of lizard boys and skin suits in Burroughs’ early novels such as The Soft Machine and The Ticket that Exploded. In many ways, Kid Chameleon isn’t far removed from the various incarnations of the Wild Boys—resourceful, shape-shifting and always a loner. By a curious coincidence Burroughs was in London writing Port of Saints, the sequel to The Wild Boys, at the time Cor!! was publishing Kid Chameleon.

There aren’t any pages online from The War of the White Eyes; perhaps that’s for the best, it would only shatter my vague memories even further. However, you can see a couple of pages from Kid Chameleon here, written by Scott Goodall. The strip was drawn by Joe Colquhoun, later the artist on Charlie’s War by Pat Mills.

There are few people who really change your life but Robert Anton Wilson—who died earlier today—certainly changed mine. Wilson’s Illuminatus! trilogy (written with Robert Shea) was my cult book when I was at school in the 1970s, a rambling, science fiction-inflected conspiracy thriller that opened the doors in my teenaged brain to (among other things) psychedelic drugs, HP Lovecraft, James Joyce, William Burroughs and Aleister Crowley as well as being a crash-course in enlightened anarchism. I’ve had people criticise the books to me since for their ransacking of popular culture but this was partly the point, they were collage works, and they worked as a perfect introduction for a young audience to worlds outside the usual circumscribed genres.

The philosophical side of Wilson’s work was probably the most important at the time (and remains so now), his “transcendental agnosticism” made me start to question the adults around me who were trying to force my life to go in a direction I wasn’t interested in at all. I’m sure I would have resisted that kind of pressure anyway but the value of RAW’s writings in Illuminatus! and the later Cosmic Trigger came with being given an intelligent rationale for those decisions; I couldn’t necessarily articulate why I was “throwing my life away” by wanting to drop out of the whole education system but Wilson’s work had convinced me it was the right thing to do. I still mark the true beginning of my life as May 1979, the month I left school for good.

He wouldn’t want us to be maudlin, I’m sure. It’s typical for a writer who spent so much of his life writing about drugs and coincidences that he managed to die on Albert Hofmann’s birthday. So I’ll just say thank you Robert, for changing my life. And Hail Eris!

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Absolute Elsewhere