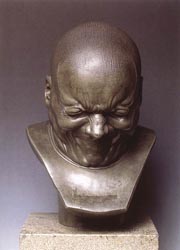

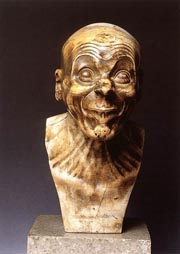

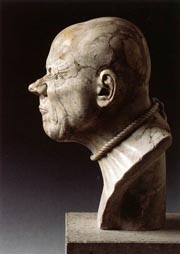

Left: The Arch-Evil by Messerschmidt, c. 1770.

The Artist Estranged by Lorenz Eitner

“TO BE IN PRESSBURG and not to visit the famous sculptor Messerschmidt would be a disgrace to the connoisseur of art,” wrote a traveller in the early 1780s, still under the fresh impression of the “Egyptian Heads,” which the unpredictable artist had allowed him to see, a privilege he did not grant to all the curious who made the tedious trip from Vienna for just this purpose. The scholar Friedrich Nicolai, luckier and more inquisitive than most, was favoured by the sculptor with a detailed, if somewhat confused, explanation of these strange works and permitted to examine his small workshop on the bank of the Danube, the entire furniture of which consisted of a bed, a flute, a tobacco-pipe, a water pitcher, an old Italian book about human proportions and the drawing of an armless Egyptian statue.

Nicolai’s visit occurred in 1781. Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, once assistant professor of sculpture at the Imperial Academy of Vienna, now necromancer and recluse, was in his forty-fifth year. A robust man, of very plain appearance and manner, he had behind him a notable, though brief, career. Trained by his uncles, the brothers Johann Baptist and Philip Jacob Straub in Munich and Graz, he had continued his studies at the Vienna Academy under the celebrated Matthaeus Dormer, and travelled to Rome and London in 1765. On his return, he was favoured with important portrait commissions for the Imperial court and the high aristocracy of Vienna. In 1769, he was appointed to an assistant professorship at the Academy, with the expectation of promotion to the chair of sculpture at the incumbent’s death. But when this occurred, in 1774, Messerschmidt was passed over, not because of intrigues against him, as he imagined, but because of a “confusion in the head” which he had suffered three years earlier and from which he still had not recovered sufficiently, according to a report to the Empress by the minister, Count Kaunitz, to qualify for the appointment. Refusing the pension which was offered him, he left Vienna, travelled in southern Germany, vainly applied for a position at the Academy of Munich in 1775, and finally settled in Pressburg in 1777. Since the onset of his illness in 1771, he had neglected his work as a portraitist, though he still received and accepted occasional commissions, and had concentrated his great industry on the production of a series of heads of very strange aspect.

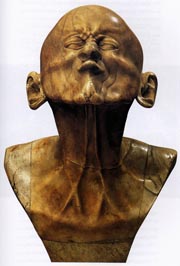

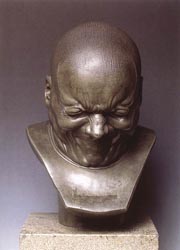

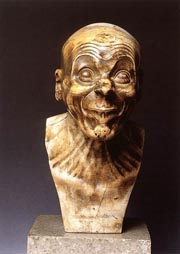

The Beaked (front view).

Nicolai found him busy with the sixty-first of these heads. He observed that it, like all the rest, was a self-portrait. The sculptor worked in front of a mirror. Pinching himself from time to time under the lowest right rib, he would cut a terrifying grimace scrutinise his face in the mirror, sculpt, and after an interval of about half a minute repeat his grimace with remarkable precision. When the courteous Nicolai asked him to explain his method, Messerschmidt, somewhat hesitatingly, gave him a confused account, the gist of which can be summed up as follows: although he had lived chastely since his youth, Messerschmidt was often visited by ghosts who caused him pains in the abdomen and thighs. Fortunately, he had managed to devise a system for warding off these tormentors. This system was based on knowledge of universal proportions, learned through the study of the Egyptian Hermes Trismegistos—of whose armless statue he always kept a drawing about him. His knowledge of proportion gave Messerschmidt the power to resist the spirits. For all things have their proper proportion, and all effects come from a sufficient cause; whoever can reproduce in himself the proportions of another being should be able to produce effects equal to the effects of the other. The Egyptian Hermes is the key to the secret of proportion; it contains the norm of the human body. Head and body correspond: every part of the face, for example, is related to some other part of the body by secret analogy.

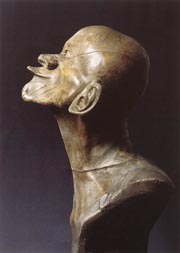

The Beaked (side view).

All this, in Messerschmidt’s opinion, amounted to a momentous discovery which, not surprisingly, had aroused the envy of the Spirit of Proportion, the chief of his ghostly persecutors. Undaunted by the pains which the spirit inflicted on him, he resolved to delve deeper into the mystery of proportion, in order to be victorious in this contest. By observing the pains which he felt in his lower body as he worked on the faces of his busts, he came to the conclusion that if he pinched himself in different parts of the body and accompanied this with grimaces which bore the exact Egyptian proportion to the pinch, he would reach perfection in the matter of proportion. He was confirmed in his idea by an English visitor who, though unable to express himself in German, managed to convey to Messerschmidt his grasp of the principle by exposing that part of his thigh which exactly corresponded to the particular portion of the head which Messerschmidt was sculpting at the moment. Pleased with his system, Messerschmidt resolved to pass it on to posterity by means of his sculpted heads, of which he planned to execute sixty-four, since there were sixty-four canonical grimaces.

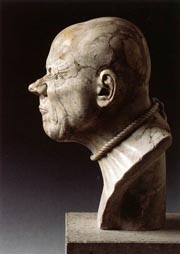

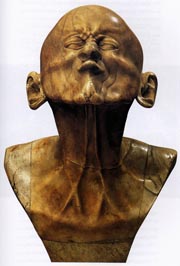

The Gentle Quiet Sleep.

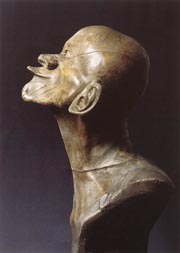

Nicolai recognised that the heads fell into three groups. There was a small number of fairly “natural” heads which showed the features of their maker slightly ennobled by a touch of stylisation, or animated by fairly restrained expression, or distorted by such normal spasms as are produced by sneezing or yawning. In sharpest contrast to this group were two completely monstrous beak-heads in which, atop painfully extended necks, the shapes of chin, mouth and nose were thrust upward and drawn together into a sharp instrument for pecking or pinching. Messerschmidt seemed afraid of these heads and admitted to Nicolai that they represented the Spirit of Proportion. The spirit had pinched him and he had pinched back; he had finally managed to carve these two heads in marble, but had almost died in the attempt. At last, the defeated spirit had left him amidst a great stench. The third and largest group, comprising 54 busts at the time of Nicolai’s visit, consisted of the convulsively grimacing heads which are still the best known of the series. All seemed to be self-portraits. Nicolai noticed that in many of them the mouths were tightly shut and the lips drawn in so as to form a thin line. Messerschmidt explained this curious feature by pointing out that men should not show the red of their lips, since animals never showed theirs—and animals, as he reminded his visitor, were superior to men in their perception of the hidden aspects of nature.

The Hanged.

Was Messerschmidt insane? This question has aroused controversy between the psychologists and the historians. The psychoanalyst Ernst Kris, who wrote two studies of Messerschmidt, the earlier of which, published in 1932, is still the most detailed account of the sculptor’s work, diagnosed his case as a “psychosis with predominant paranoid trends, which fits the general picture of schizophrenia.” In Kris’s hands, the rather meagre evidence yielded a surprisingly large and varied set of meanings. Messerschmidt’s bouts with the ghosts turned out to reveal his latent homosexuality, the tightly closed lips of some of his heads to express a defensive reaction against the aggressive spirits who would force or seduce him into serving them in a female role, while the open mouth or flaccid lips of certain other heads represented a yielding to the sexual importunities of the demons. When pinching his ribs, Messerschmidt—according to Kris—acted under two quite different impulses, “castration anxiety,” on the one hand, which drove him to “prove that the rib is still there, from which God has created the woman,” and, on the other hand, a megalomanic identification with God—”while working he felt his own ribs in order to create human figures.”

The Lecher.

Considered from another angle it is amusing to compare this formidable analysis with the more modest one proposed by Nicolai, who, unlike the later diagnosticians, had the advantage of being personally acquainted with the patient. To this eighteenth-century materialist, the case seemed simple: Messerschmidt’s sedentary life, his recurrent abdominal pains, the relief which he obtained from pinching himself under the rib cage and the bad odours which accompanied the departing tormentors proved that the sculptor’s troubles stemmed from indigestion, complicated by his superstitious bent which made him attribute natural events to occult causes. This last defect Nicolai blamed on Messerschmidt’s imagination, his solitude, gullibility and the influence of charlatans; he did not consider him to be truly mad. Modern scholars have not taken up Nicolai’s suggestion, though they have leaned heavily on the rest of his account. But something akin to his humanist scepticism flavours the critique to which the art historians Rudolf and Margot Wittkower subjected Kris’s psychoanalysis of Messerschmidt in their book Born under Saturn. They contend that, however mad Messerschmidt may have been in the opinion of modem psychiatrists, it is clear that much of his work, down to the end of his life, was entirely “normal,” and that even the strange heads for which he has become famous can best be understood as works of art conditioned by an historical situation, rather than as the morbid symptoms of a solitary lunatic.

It is difficult to apply the terms of insanity or normalcy to art. Strictly speaking, their meaning is medical or social. Applied to art, they make little sense: what work of art is “normal?” What are the specific characteristics of insanity in art? Besides, like notions of beauty, notions of sanity fluctuate from one period to the next. Pressburg in 1781 tolerated Messerschmidt, just as London tolerated Blake, another seer of ghosts; today, both men would very likely be institutionalised. Certain aspects of Messerschmidt’s strange personality were in his time considered to be within the bounds, or on the fringes, of convention. His belief in ghosts and methods of exorcism were no more absurd than some of the medicine or priest-craft widely practised in his day by men reputed sane. His interest in the occult, in magic proportions and in physiognomy reflected popular pseudo-science, as propagated by such respected charlatans as Mesmer, Lavater and Gall.

But there is danger in over-stressing the ties which bound him to his time. The seemingly conventional character of some of his late work is deceptive and invites misinterpretation. The magic heads, for example, are still commonly called “character heads,” because they recall Lavater’s physiognomic typology or because they bear a superficial resemblance to the familiar academic studies of the passions. The fanciful titles which were attached to them shortly after Messerschmidt’s death represent an early attempt to minimise their uncanny strangeness. Actually, it is evident that, far from illustrating a variety of types, they repeat over and over one particular face—Messerschmidt’s own. And it is equally clear that they exhibit only a very limited range of expressions, few of them corresponding to any recognisable emotion. The majority show deliberate grimaces, mask-like in their schematic artificiality. They bear out, in other words, Nicolai’s account of Messerschmidt’s intention, which links them more closely with primitive image magic than with eighteenth-century pseudo-science.

Messerschmidt was neither in tune with his time, nor entirely alienated from it. His artistic personality was injured, but not debilitated, by sickness; the conflict within him irritated his imagination and concentrated his energies: it was the fortunate flaw which raised his later above his earlier works and above those of his more ordinary contemporaries. Seen purely from the point of view of style and execution, the famous heads show no signs of abnormality, unless their perfect finish and Messerschmidt’s deliberate choice of hard and polished materials is to be considered as perverse or obsessive. The execution is never spontaneous; even the weirdest heads are elegantly cut in marble or exquisitely cast in shining metal. Throughout the entire series, Messerschmidt’s technical mastery never falters. This steadiness, this constant assurance and concentration prove that in the midst of his delusions he retained control of all his conscious resources, never falling into incoherence, rambling, or vacant embroidering. While in some details, especially of hair and skin, traces of Rococo vivacity linger, distantly recalling Messerschmidt’s earlier, sumptuous court portraiture, the general treatment of the heads is bare, hard and Spartan; seen at a distance, they remind one of the compact strength and severity of Roman portraits. They express a deliberate reaction against baroque opulence and prove Messerschmidt to have been a pioneer of the Neo-Classical movement. Set against the background of the general history of style in their time, his bizarre heads do not appear as freaks, but as the work of a progressive and cosmopolitan artist, aware of the issues of his day. It is noteworthy that those heads of the series which are the most advanced stylistically are also the most fantastic, while the relatively “normal” ones are treated in a more conservative manner. What gives to all of them a peculiar intensity-quite apart from their obvious strangeness-is the way in which Messerschmidt has been able to combine representation with rigid stylisation, expression with abstract pattern, and preserve, at the same time, both the anatomical structure and the character of portrait. To bring these divergent elements into harmony was the work of a powerful artistic intelligence.

From The Grand Eccentrics, edited by Thomas B Hess and John Ashbery, Collier Books, 1971.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive