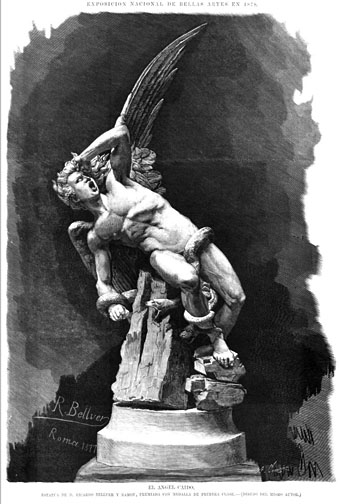

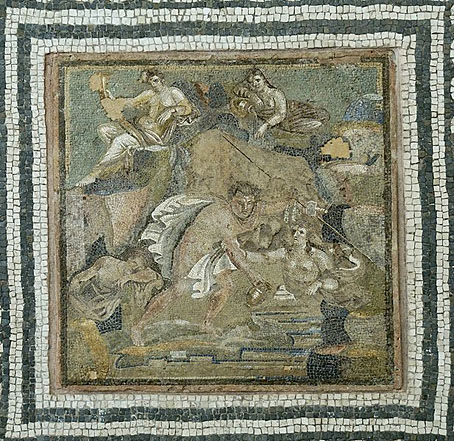

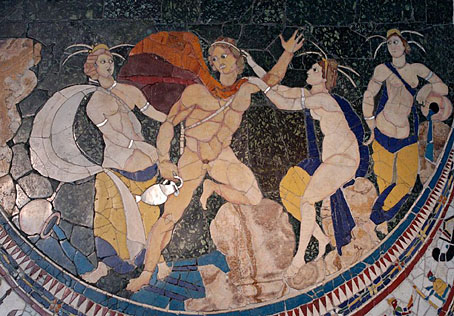

Mosaic with Hylas and Nymphs from Tor Bella Monaca, Rome (2nd century BC).

Among the myths to which Greek lovers referred with pride, besides that of Achilles, were the legends of Theseus and Peirithous, of Orestes and Pylades, of Talos and Rhadamanthus, of Damon and Pythias. Nearly all the Greek gods, except, I think, oddly enough, Ares, were famous for their love. Poseidon, according to Pindar, loved Pelops; Zeus, besides Ganymede, was said to have carried off Chrysippus. Apollo loved Ayacinth, and numbered among his favourites Branchos and Claros. Pan loved Cyparissus, and the spirit of the evening star loved Hymenæus. Hypnos, the god of slumber, loved Endymion, and sent him to sleep with open eyes, in order that he might always gaze upon their beauty. (Ath. xiii. 564). The myths of Phœbus, Pan, and Hesperus, it may be said in passing, are paiderastic parallels to the tales of Adonis and Daphne. They do not represent the specific quality of national Greek love at all in the same way as the legends of Achilles, Theseus, Pylades, and Pythias. We find in them merely a beautiful and romantic play of the mythopœic fancy, after paiderastia had taken hold on the imagination of the race. The case is different with Herakles, the patron, eponym, and ancestor of Dorian Hellas. He was a boy-lover of the true heroic type. In the innumerable amours ascribed to him we always discern the note of martial comradeship. His passion for Iolaus was so famous that lovers swore their oaths upon the Theban’s tomb; while the story of his loss of Hylas supplied Greek poets with one of their most charming subjects. From the idyll of Theocritus called Hylas we learn some details about the relation between lover and beloved, according to the heroic ideal…

A Problem in Greek Ethics; Being an Inquiry into the Phenomenon of Sexual Inversion (1883/1908) by John Addington Symonds

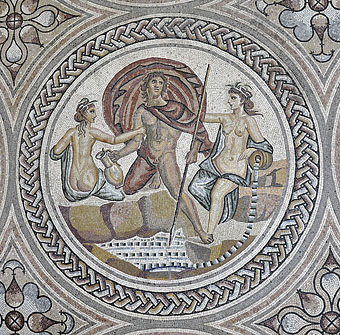

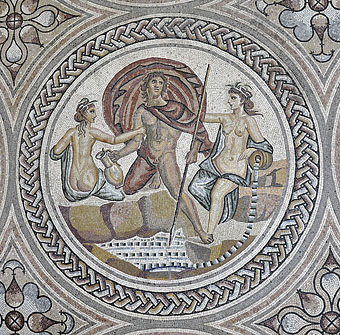

Hylas mosaic, Saint-Romain-en-Gal-Vienne, France (3rd century).

Not for us only, Nicias, (vain the dream,)

Sprung from what god soe’er, was Eros born:

Not to us only grace doth graceful seem,

Frail things who wot not of the coming morn.

No—for Amphitryon’s iron-hearted son [Heracles],

Who braved the lion, was the slave of one:—

A fair curled creature, Hylas was his name.

He taught him, as a father might his child,

All songs whereby himself had risen to fame;

Nor ever from his side would be beguiled

When noon was high, nor when white steeds convey

Back to heaven’s gates the chariot of the day,

Nor when the hen’s shrill brood becomes aware

Of bed-time, as the mother’s flapping wings

Shadow the dust-browned beam. ‘Twas all his care

To shape unto his own imaginings

And to the harness train his favourite youth,

Till he became a man in very truth.

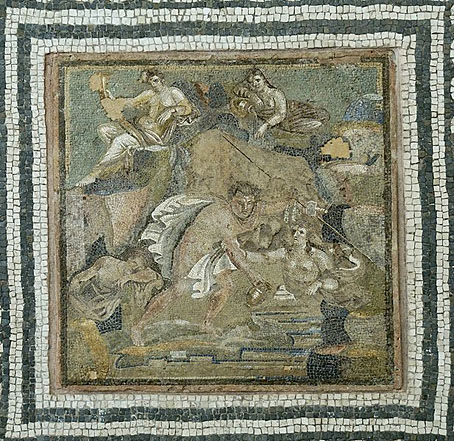

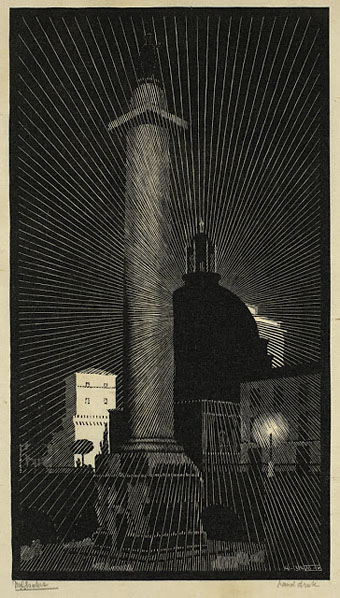

Rape of Hylas mosaic from the Basilica of Junius Bassus, Rome (first half of the 4th century).

Water the fair lad wont to seek and bring

To Heracles and stalwart Telamon,

(The comrades aye partook each other’s fare,)

Bearing a brazen pitcher. And anon,

Where the ground dipt, a fountain he espied,

And rushes growing green about its side.

There rose the sea-blue swallow-wort, and there

The pale-hued maidenhair, with parsley green

And vagrant marsh-flowers; and a revel rare

In the pool’s midst the water-nymphs were seen

To hold, those maidens of unslumbrous eyes

Whom the belated peasant sees and flies.

And fast did Malis and Eunica cling,

And young Nychea with her April face,

To the lad’s hand, as stooping o’er the spring

He dipt his pitcher. For the young Greek’s grace

Made their soft senses reel; and down he fell,

All of a sudden, into that black well.

Theocritus, Idyll XIII: Hylas (translated by CS Calverley)

Hylas and the Nymphs (1635) by Francesco Furini.

Hylas with the Golden Jug (c.1650) by Il Volterrano (Baldassare Franceschini).

Continue reading “A fair curled creature, Hylas was his name”