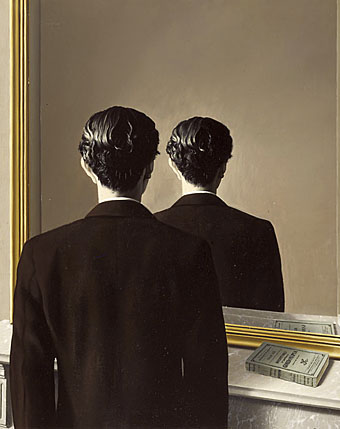

Edward James by René Magritte, La Reproduction Interdite (1937).

Art collector Edward James (1907–1984) was a characteristically English eccentric, a kind of 20th century equivalent of William Beckford or Horace Walpole, who was captivated by Surrealism in the 1930s and became a lifelong devotee of the movement. Much of his inherited wealth was spent supporting artists such as Salvador Dalí, René Magritte and Lenora Carrington and his homes at Monkton House and Walpole Street in London were transformed into showcases of Surrealist decor; Dalí’s famous sofa modelled on Mae West’s lips was designed with assistance from James.