XII Festival de Almagro (1989).

Dura el Tránsito (1981).

José Hernández Spanish painter and engraver.

Update: José Hernandez at Velly.org.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

• The etching and engraving archive

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Painting

XII Festival de Almagro (1989).

Dura el Tránsito (1981).

José Hernández Spanish painter and engraver.

Update: José Hernandez at Velly.org.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

• The etching and engraving archive

We had Sartorio’s Gorgon and the Heroes yesterday so here’s some Medusas to continue the theme. Art history, especially in the nineteenth century, is full of Medusa portraits; these are some of the better ones.

Medusa by Caravaggio (1598-1599).

Head of Medusa by Peter Paul Rubens (1617).

Giulio Aristide Sartorio is generally counted as one of the Italian Symbolists, along with painters such as Giovanni Segantini. He’s also one of the few notable artists of the period to have worked as a film director.

I’ve been fascinated by the curiously erotic academic style of Sartorio’s early work for years but these paintings rarely appear in books (although there have been a couple of monographs) and there’s little decent attention given to him on the web. Philippe Jullian in his essential guide to Symbolism, Dreamers of Decadence (Pall Mall Press, 1971), describes his work as being “vast paintings… full of handsome warriors who are always naked and generally dead.” Gabriele D’Annunzio, who knew heroic camp when he saw it, became a fan when the pair met in Rome in the 1880s. Sartorio illustrated D’Annunzio’s Isaotta Guttadàuro in 1886 and they continued to collaborate into the 1920s. One possible reason for Sartorio’s falling out of favour may have been later association with Mussolini’s Fascists, something else he shared with D’Annunzio.

Diana of Ephesus and the Slaves (1893–98).

Much as I’d like to point you to a large reproduction of the bizarre Diana of Ephesus and the Slaves, there doesn’t seem to be one around just now. However, you can see a few gallery pages of Sartorio’s work here if you don’t mind the copyright label spoiling everything.

Update: A reasonable copy of the Diana painting has turned up. Click the image above.

Diana of Ephesus and the Slaves (detail).

Gorgon and the Heroes (1895–99).

L’Invasione degli Unni (no date).

Siren or The Green Abyss (1900).

Pico, roi du Latium, et Circé de Thessalie (1904).

Pico, roi du Latium (detail).

Ex libris Gabrielis Nuncii “per non dormire” (1906).

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Angels 4: Fallen angels

The riddle of the rocks by Jonathan Jones

It was the art movement that shocked the world. It was sexy, weird and dangerous—and it’s still hugely influential today. Jonathan Jones travels to the coast of Spain to explore the landscape that inspired Salvador Dalí, the greatest surrealist of them all.

The Guardian, Monday March 5, 2007

I AM SCRAMBLING over the rocks that dominate the coastline of Cadaqués in north-east Spain. They look like crumbling chunks of bread floating on a soup of seawater. Surreal is a word we throw about easily today, almost a century after it was coined by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Yet if there is anywhere on earth you can still hope to put a precise and historical meaning on the “surreal” and “surrealism”, it is among these rocks. To scramble over them is to enter a world of distorted scale inhabited by tiny monsters. Armoured invertebrates crawl about on barely submerged formations. I reach into the water for a shell and the orange pincers of a hermit crab flick my fingers away.

The entire history of surrealism—from the collages of Max Ernst to Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone—can be read in these igneous formations, just as surely as they unfold the geological history of Catalonia.

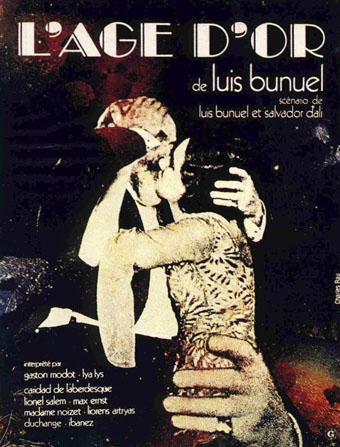

I sit down on a jagged ridge. What if I fell? Would they find a skeleton looking just like the bones of the four dead bishops in L’Age d’Or, the surrealist film Luis Buñuel shot here in 1930?

Buñuel had been shown these rocks by his college friend Dalí years earlier. It was here they had scripted their infamous film Un Chien Andalou. Dalí came from Figueras, on the Ampurdán plain beyond the mountains that enclose Cadaqués, and spent his childhood summers here, exploring the rock pools and being cruel to the sea creatures. In most people’s eyes, this is a beautiful Mediterranean setting. It certainly looked lovely to Dalí’s close friend, the poet Federico García Lorca, when Dalí brought him here in the 1920s: in his Ode to Salvador Dalí, Lorca lyrically praises the moon reflected in the calm, wide bay…

Continues here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The persistence of DNA

• Salvador Dalí’s apocalyptic happening

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch

• Dalí Atomicus

• Las Pozas and Edward James

• Impressions de la Haute Mongolie

Major art exhibition at the Cartier Foundation opens today.

And while we’re on the subject, let’s not forget Inland Empire.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Inland Empire