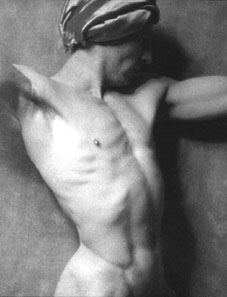

Left: Stowitts photgraphed by Nickolas Muray, 1922.

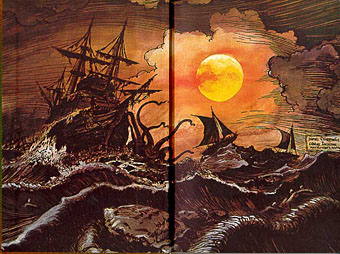

Hubert Julian Stowitts had a number of careers, including dancer, film actor, painter, designer and metaphysician. As a dancer he worked with Anna Pavlova, who discovered him in California in 1915 and took him on tour around the world. His statuesque figure was used by Rex Ingram for the infernal scenes in The Magician (1926), an adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s rather limp roman-à-clef based on the exploits of Aleister Crowley. The scene with Stowitts as a satyr owed nothing to the book, however, being more inspired by the director’s fondness for the tales of Arthur Machen. Most photos that turn up from this film show Stowitts rather than Paul Wegener who played the sinister alchemist of the title.

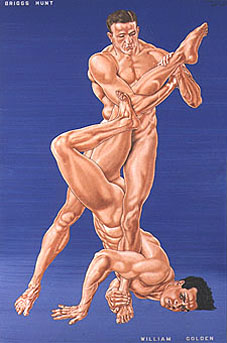

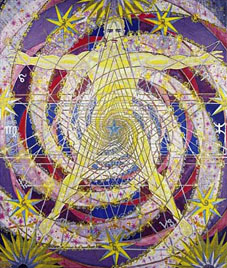

Stowitt’s painting developed in the 1930s and included a series of 55 paintings of nude (male) athletes for the 1936 Olympics (see Ewoud Broeksma’s contemporary equivalents at originalolympics.com). Other paintings depicted dance scenes, costume designs, people encountered during travels in the Far East and, in the 1950s, a series of ten Theosophist pictures entitled The Atomic Age Suite.

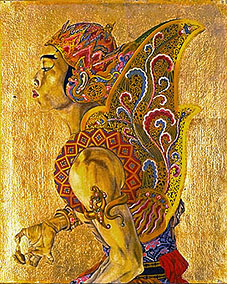

Prince Suwarno in Mahabarata role (1928).

Briggs Hunt and William Golden (1936).

The Crucifixion in Space (1950).

• The Stowitts Museum and Library

• Stowitts at the Queer Arts Resource

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Nicholas Kalmakoff, 1873–1955