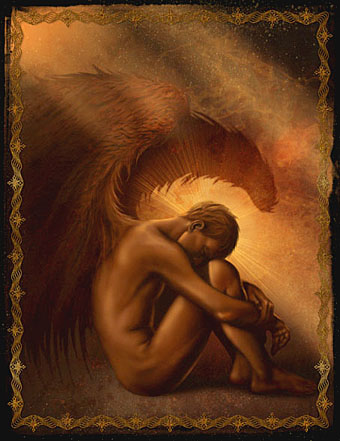

On Monday Eroom Nala mentioned my Fallen Angel picture in one of the comments for the first angel posting. Here’s the picture in question (from 2004).

As I mentioned earlier, this was based on Jeune homme assis au bord de la mer (Young Man Sitting by the Seashore, 1836), the most well-known painting by Jean Hippolyte Flandrin (1809–1864). In a posting back in February I wrote about how this painting has become something of a gay icon over 170 years, with increasing numbers of artists and photographers working their own variations on the pose. As far as I was aware, I was the only person to have tried adding wings to the figure.

Now today I run across a great gallery of photographs by Jose Manchado who has his rather gorgeous model, Reuben, adopt the same pose then gives him a set of abstract wings.

Manchado’s other photographs are well worth a look. He also adds more realistic wings to a female model but since we’re concerning ourselves with male angels this week I’ll leave you to look for her.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

• The recurrent pose archive