The first question has to be “Bertrand who?” but you won’t receive an answer here since information is scarce (see below). Bertrand’s erotic surrealism first appeared in the late Sixties, going by the dates in collections of his work. Some of his paintings and drawings crept into the underground mags of the period then turned up in odd places throughout the Seventies. The first I saw of any Bertrand art was on the cover of the pre-Savoy publication, Wordworks #6, and a music paper ad for the Chrome 12″, Inworlds.

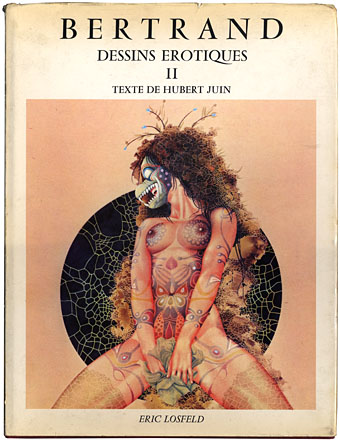

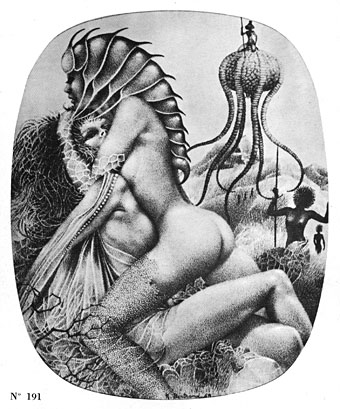

French porn publisher Eric Losfeld produced a couple of large, limited edition collections of Bertrand’s work in the early Seventies. All the drawings reproduced here are from the battered 1971 volume shown above. If it seems surprising that these haven’t been reprinted it may be that Bertrand’s concerns are too weird or simply too unpleasant for contemporary tastes. Many of his ink drawings, and some of his paintings, seem to have begun life as decalcomania splotches, a Surrealist technique invented by Oscar Dominguez as a means of injecting chance into the creative process. Decalcomania produces random patterns which the artist then elaborates upon. Max Ernst’s famous Europe After the Rain, and a number of his other paintings from the 1940s, began life as a field of vaguely organic marks created by pressing thickly applied paint to the canvas with a sheet of glass or paper. Bertrand used ink stains in a similar way, with the result that most of his doe-eyed female figures (and his figures are nearly always women) are fringed by leafy or fungal growths. Many of his scenes are a kind of lesbian equivalent of the human/alien entanglements one finds in William Burroughs’ more elaborate flights of fancy. If his women aren’t being absorbed into some organic mass, they’re often being subject to investigation (even impalement) by spikes or claws, and here we perhaps find the reason his work remains out of print. Feminists then and now would have taken a dim view of Bertrand’s more violent works; even if Taschen did produce a Bertrand collection, it’s unlikely that many of the more grotesque pictures would be included.

All the pictures in the Losfeld books were produced in a short period from 1967–69. What happened to Bertrand afterwards remains a mystery. Did he decide to do pursue a different, more commercial direction? Is he still alive? The books offer no clue but maybe someone out there has the answer.

Update: Nathalie discovers that the artist in question is Raymond Bertrand, and more of his work can be seen here.

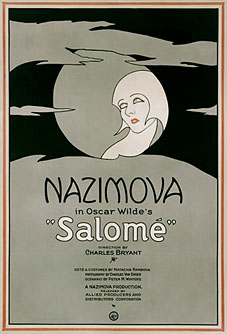

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or