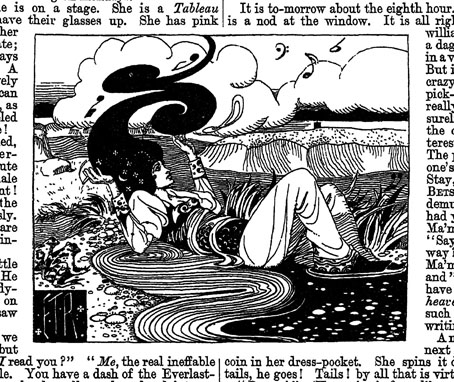

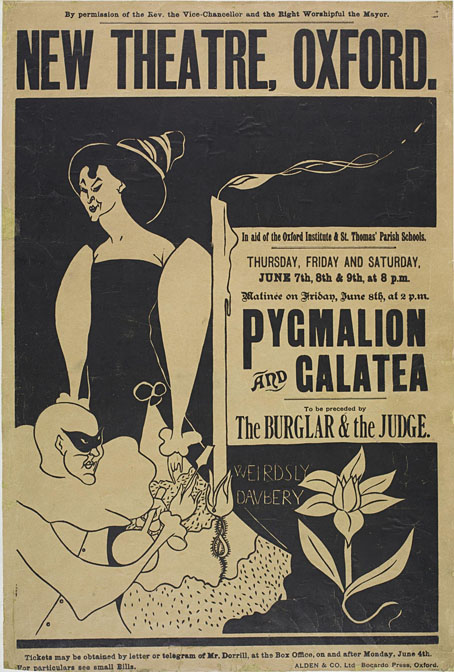

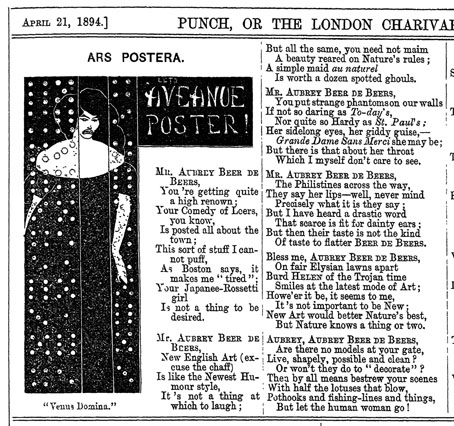

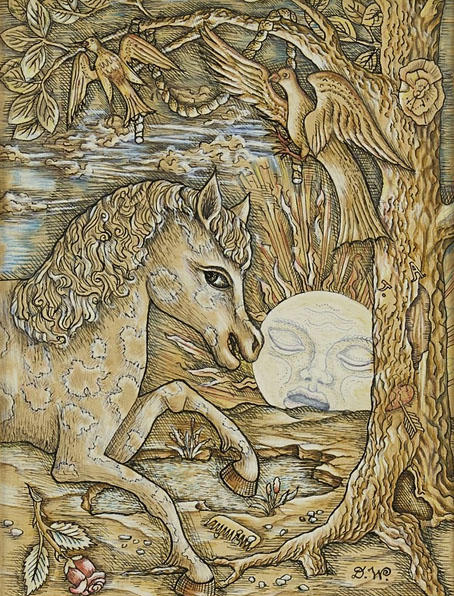

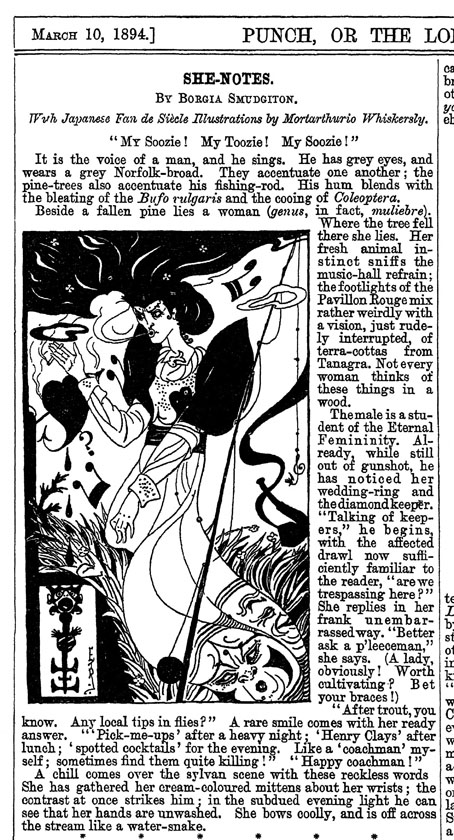

You think you’ve seen all of the Aubrey Beardsley parodies then another one turns up… This poster by James Hearn dates from 1894, the year that Beardsley’s art became a succès de scandale thanks to his illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s Salome and his covers for The Yellow Book. Beardsley’s art was so original that the parodies arrived swiftly and continued into the following year, until the downfall of Oscar Wilde affected the artist’s position at The Yellow Book and rendered his person, as well as his drawings, even less palatable to the general public. Hearn’s piece is rather poor in comparison to the jibes in Punch magazine, and unusual for being part of a functional design rather than a satirical item.

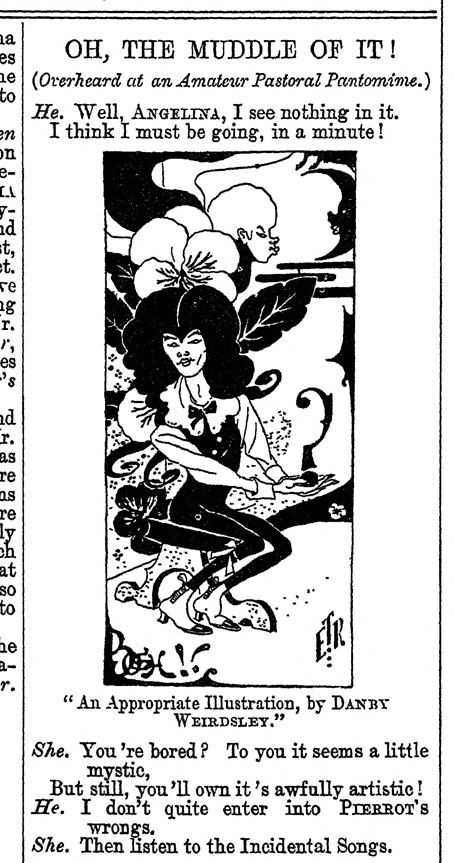

The Punch parodies, several of which worked their own transformations of the artist’s name, used to be available for viewing on a university website, but as I was saying in the previous post, these places have a tendency to vanish when you go to revisit them. The Hearn poster is part of the V&A’s collection but everything else here is from scans of Punch at the Internet Archive. Back issues of the magazine, even those from the 19th century, haven’t always been easy to find online. Punch only gave up the ghost in 2002, and it seems that the restriction on publishing its more recent contents has affected even the older issues, so that the copies at the University of Heidelberg, for example, can only be seen by visiting the university library. It was worth looking for all of these, however. In addition to the drawings you can also see whatever text came with them, while one of the volumes for 1894 also includes a parody of Oscar Wilde’s The Sphinx, together with an illustration that lampoons the poem’s illustrations by Charles Ricketts. The Beardsley parodies are by ET Reed and Linley Sambourne for the most part, although none are credited as such.