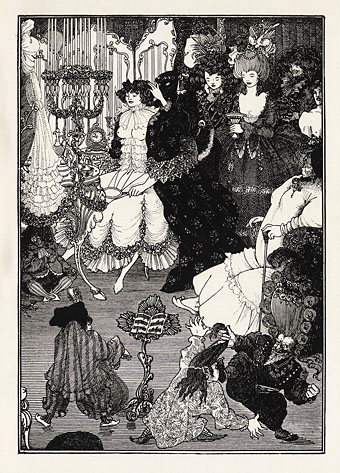

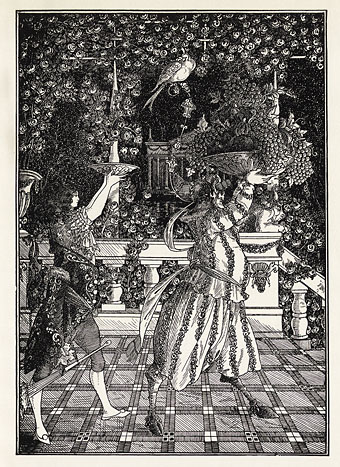

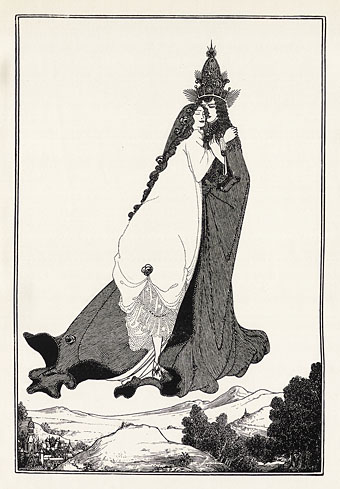

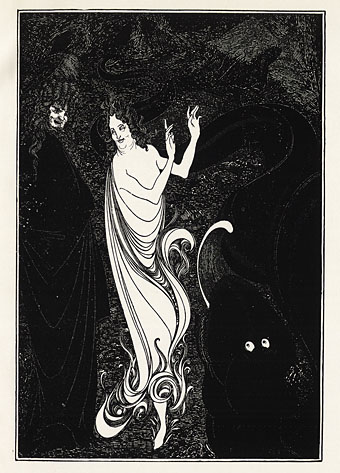

Aubrey Beardsley’s drawings are reprinted endlessly but his writings receive less attention even though he lavished as much care on his literary efforts as he did on his illustrations. The major work is his unfinished novel, Under the Hill, a book whose descriptive filigree is as detailed as the drawings which accompany the text, and whose erotic passages ensured that the story was never published in full during his lifetime. Extracts appeared with illustrations in The Savoy, the magazine for which Beardsley was art editor; after Beardsley’s death a longer expurgated version was published by John Lane in 1903, together with Beardsley’s other writings including two pieces of verse, The Three Musicians and Ballad of a Barber.

The Lane volume is a recent arrival at the Internet Archive, and while most of the material is familiar to me it does feature a few pages of Beardsley’s table talk which I’d never seen before. The expurgated Under the Hill is worth reading as an introduction to Aubrey’s florid writing style (and his obsession with clothing) but so much is missing that it can’t be considered representative of the author’s intentions. Under the Hill was published in full in 1907 in a private edition by Leonard Smithers, but the book had to wait until 1959 to receive a more public presentation when Olympia Press added it to their famous Traveller’s Companion series. The Olympia edition has the additional benefit of being completed by John Glassco, a bisexual Canadian poet, and accomplished pasticheur of erotic literature. Glassco not only matches Beardsley’s style while completing the story, he also provides a detailed history of the text, and a defence of its value as literature. If you’re a Beardsley enthusiast who already has most of the artwork then the Olympia book is worth seeking out.

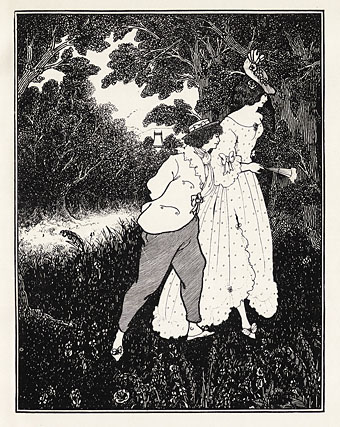

New English Library reprint, 1966.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Aubrey Beardsley archive