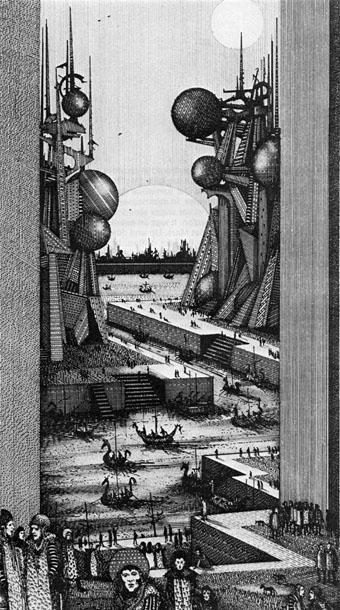

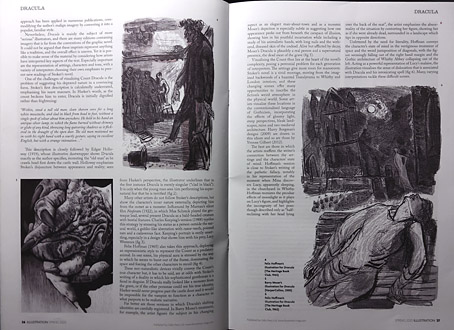

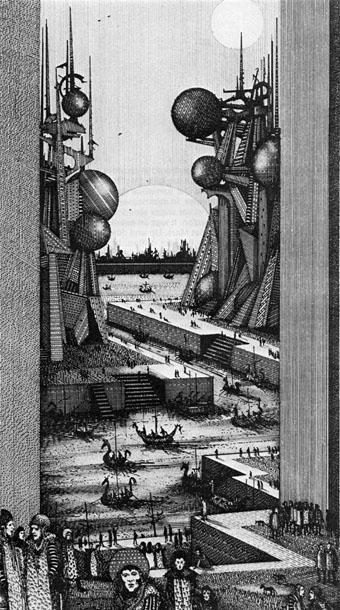

One of Ian Miller‘s drawings from the illustrated edition of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, 1979.

• “I always said we were kind of an electronic punk band, really. We were never New Romantics, I don’t like it when we get lumped in with that.” Dave Ball of Soft Cell and The Grid talking to Duncan Seaman about his autobiography, Electronic Boy: My Life In and Out of Soft Cell. I’ll now be waiting impatiently for the unreleased Robert Fripp/Grid album to appear.

• “[Patricia] Highsmith’s writing—often eviscerating, always uncomfortable—has never been more relevant,” says Sarah Hilary.

• Ron Peck’s debut feature, Nighthawks (1978), is “a nuanced look at gay life in London,” says Melissa Anderson.

And then there are those figures who seem to flit around the edges of movements without ever being fully involved in any of them, who pursue their own eccentric paths no matter what is going on around them. These are the writers who make up the secret history of literature, the hidden history that’s not easily reduced to movements or trends, and who always waver on the verge of invisibility until you stumble by accident onto one of their books and realize how good they actually are, and wonder, Why wasn’t I told to read this before? But of course you already know the answer: You were not told because it doesn’t fit smoothly into the story those in authority made up about what literature is—it disrupts, it can’t be reduced to the literary equivalent of a meme.

That’s the kind of writer Pierre Klossowski (1905–2001) is. He is not a joiner. He has his own particular and often peculiar concerns, and pursues them. He does not particularly welcome you in. The content of his writing, too, has the feel of a gnostic text, as if you are reading something that, if only you were properly initiated, you would understand in a different way. In that sense his work has an esoteric or occult quality to it—and likewise in the sense that it returns again and again to the intersection of religion and pornography, the sacred and the profane.

Brian Evenson on The Suspended Vocation by Pierre Klossowski

• Chad Van Gaalen creates a psychedelic animation for Seductive Fantasy by the Sun Ra Arkestra.

• More sneak peeks from the forthcoming The Art Of The Occult by S. Elizabeth.

• More Robert Fripp: Richard Metzger on Fripp’s sui generis solo album, Exposure.

• Pamela Hutchinson on the pleasures of David Lynch’s YouTube channel.

• Mix of the week: a second Jon Hassell tribute mix by Dave Maier.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Ferdinand presents…Dark Entries Day.

• 15 fascinating art documentaries to watch now.

• Soft Power by Patten.

• RIP Milton Glaser.

• hauntología

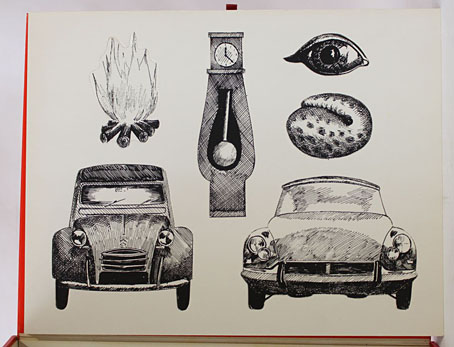

• Aquarium (1992) by The Grid (with Robert Fripp) | Soft Power (2005) by Ladytron | The Martian Chronicles (2007) by Dimension X