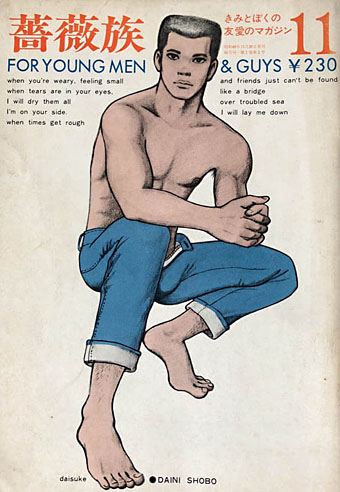

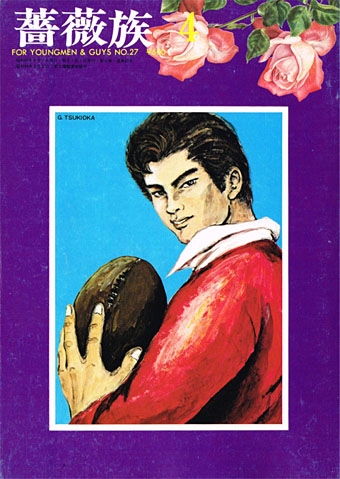

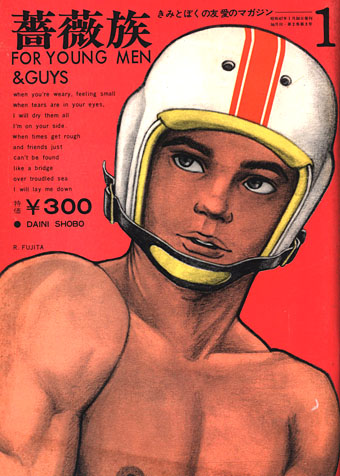

Barazoku (“The rose tribe”) wasn’t the first Japanese magazine for gay men but it was the first such title with a general circulation, as well as the longest running. 400 issues were published from 1971 to 2008. I wasn’t aware until I started reading about the history of this magazine that bara (“rose”) was originally a pejorative term like “pansy”. As with many slang terms, not least “gay”, the meaning and application has evolved over time. Use of “bara” today is confused by its application in the West to almost any form of gay manga that isn’t yaoi, a utilization that some Japanese artists take issue with.

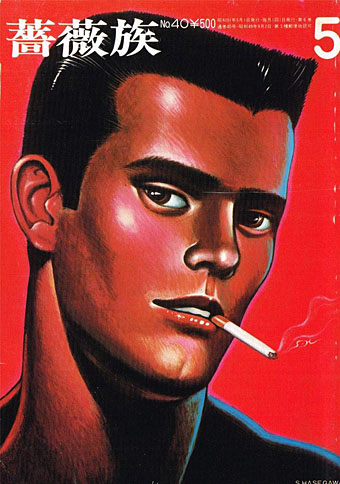

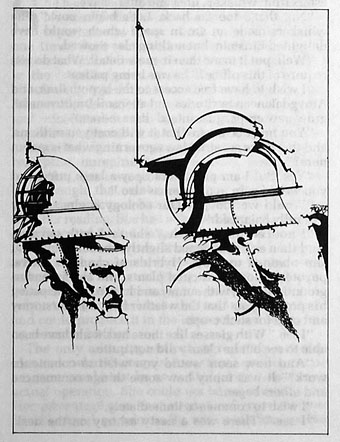

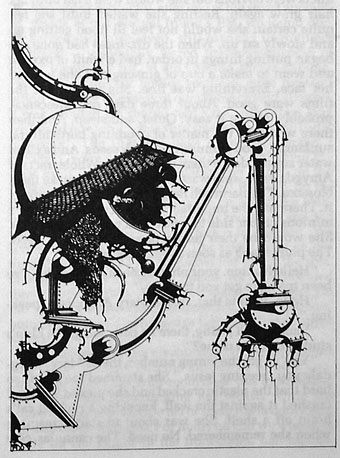

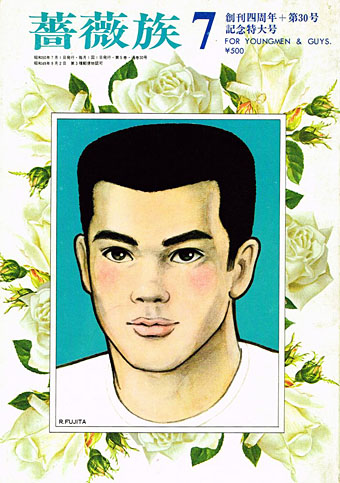

For Western viewers, the most immediately striking thing about the covers of Barazoku is their reliance on drawings or paintings rather than photographs. This isn’t entirely unprecedented—Physique Pictorial and Fizeek in the US used drawn covers from time to time—but making artwork a consistent cover feature is very unusual. (The first few covers also feature extracts from the lyrics of Bridge Over Troubled Water…) Some of the men who provided covers or interior art have appeared here in the past, among them Ben Kimura, Go Mishima and Sadao Hasegawa. The covers signed “Rune” are the work of Rune Naito (1932–2007), an artist better known in Japan for having popularised the kawaii aesthetic with his drawings of large-eyed girls and panda bears.