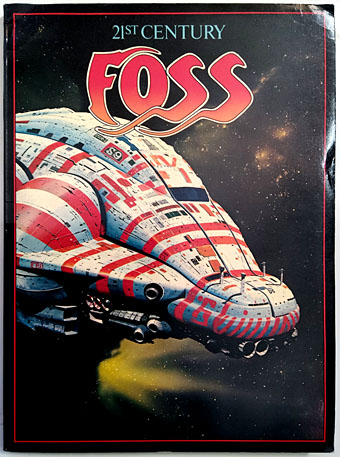

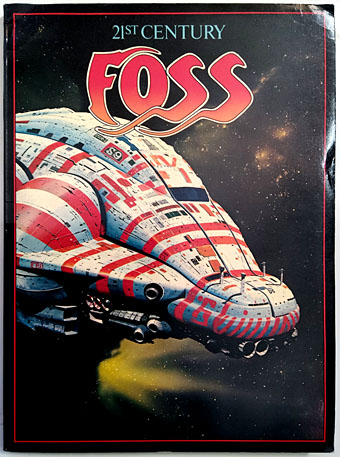

Discovered last week in a local charity shop (and for a fraction of the usual asking price), 21st Century Foss, the Dragon’s Dream collection of Chris Foss paintings from 1978. Foss’s book covers were impossible to avoid in the Britain of the 1970s, often to a ridiculous degree when publishers would stick a spacecraft by the artist or one of his imitators on a book containing no spaceships at all. His ubiquity made him the first cover artist who registered with me as exactly that, an identifiable name whose work suggested that this kind of artistic activity might be something worth pursuing.

I bought a few of the books published by Dragon’s Dream/Paper Tiger in the late 70s/early 80s but many of them weren’t interesting enough to warrant the exhausting of my meagre finances. Ian Miller, yes; Chris Foss, no. Architecture, whether real or invented, was generally more interesting than spaceships, even when the latter were unique designs like the typical Foss behemoth. (There is architecture in many of Foss’s paintings but I preferred Roger Dean’s aesthetics, the fluid and organic buildings, the vehicles modelled on birds, fish and insects.) Foss also suffered from that process of mental evolution whereby you reject an early enthusiasm when you find something that has a more obsessive hold. In musical terms, his paintings were like glam pop, the first music that made a deep impression but which was swiftly displaced by progressive rock and electronic music. Despite the repudiation I still get a weird charge when I see one of his paintings, an instant jolt back to an adolescent mental space. His cover for Midsummer Century by James Blish does this to an excessive degree, being one of a handful of Foss pictures that caused me to attempt some imitative drawings of my own circa 1975. Those drawings, which went astray years ago, caused a minor stir of appreciation among schoolfriends, a reaction that made me realise I was doing something right, however amateurish the attempt.

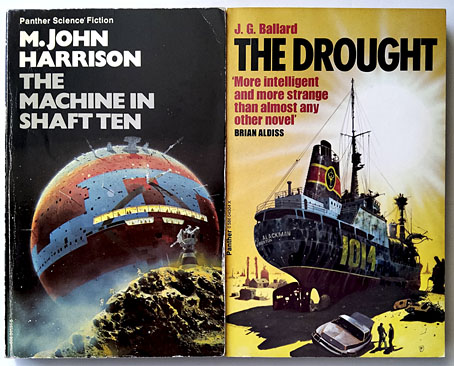

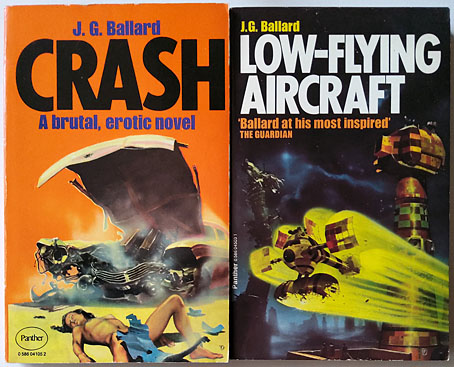

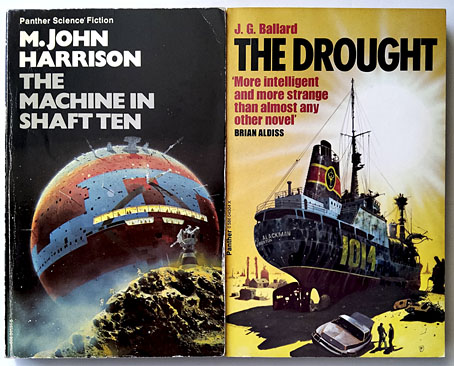

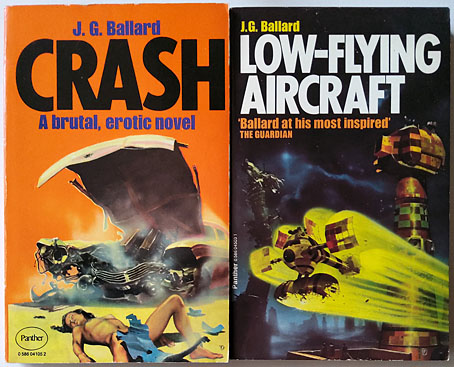

Ballard’s Low-Flying Aircraft collection is labelled on the rear as “Fiction”, and is spaceship-free, whatever the cover may suggest.

21st Century Foss belies its title by being more than a simple parade of spacecraft designs. There are Foss covers that you never see in internet galleries—pictures of submarines, ships and aircraft from the Second World War—together with a few pieces used on the covers of crank titles. Ballard aficionados may like to know that the cover for the Panther paperback of Crash is reproduced here on a full page. The latter is a good example of the thinking in paperback publishing at the time: “Ballard is science fiction so we need an SF artist for this one!” Foss had earlier illustrated two volumes of The Joy of Sex so must have seemed an ideal match. According to Rick Poynor, the artist hated the novel while the author disliked the cover.

Foss’s book opens with a section about his designs for three feature films: Jodorowsky’s Dune, Superman and Alien. None of his concepts ended up on the screen but it’s good to see the Dune designs in print. This section is also prefaced by two pages of hyperactive hyperbole for Foss and his art from Alejandro Jodorowsky. The same text may be found at Duneinfo but it bears repeating here as a further example of the manic director in full flight. Incidentally, the “English magazine” that’s referred to is most likely Science Fiction Monthly for February 1974, an issue which contained a collection of Foss paintings plus an interview with the artist.

Continue reading “Foss, Jodorowsky and low-flying spacecraft”