I’m still reading through Umberto Eco’s essays in between various novels, the current Eco volume being Chronicles of a Liquid Society, a book which includes an appraisal of the works of Jules Verne. Enthusiastic remarks about engraved illustrations are uncommon things so I wanted to draw attention to the following:

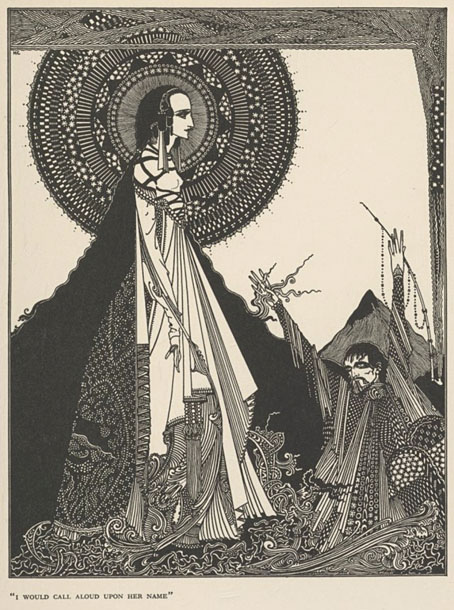

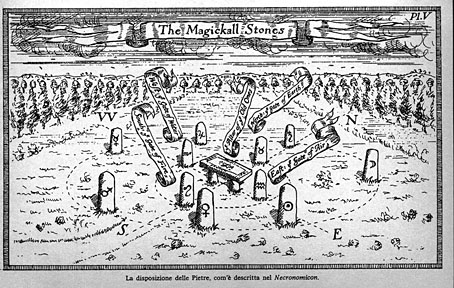

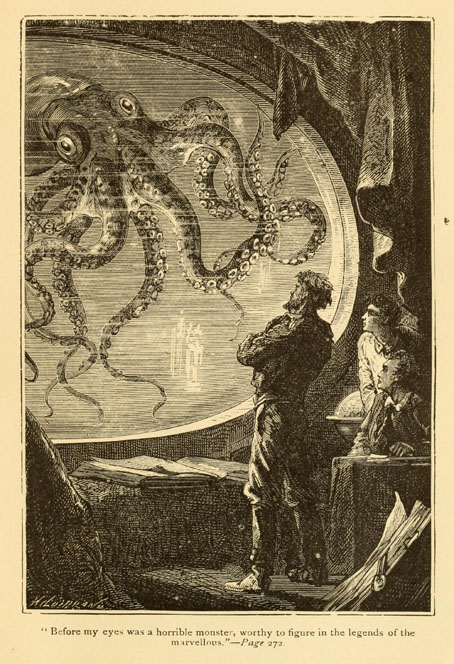

Verne’s engravings are far more mysterious and intriguing, and they make you want to examine them through a magnifying glass. Captain Nemo, who sees the giant octopus from the large porthole of the Nautilus; Robur’s airship bristling with high-tech masts; the balloon that crashes down on the Mysterious Island (“Are we rising again?” “No. On the contrary.” “Are we descending?” “Worse than that, captain! We are falling!”); the enormous projectile that points toward the Moon; the caves at the centre of the Earth—all are images that emerge from a dark background, outlines with thin black strokes alternating with whitish gashes, a universe without areas of uniform colour, a vision scratched and scored, reflections that dazzle for lack of any strokes, a world seen by an animal with a retina all its own, as seen perhaps by oxen or dogs or lizards, a world glimpsed at night through the thin slats of a venetian blind, a territory always rather nocturnal and almost subaqueous, even in full daylight, made with the dots and abrasions that generate light only where the engraver’s tool has dug or left the surface in relief.

The illustrators of Captain Nemo’s adventures were Alphonse de Neuville and Édouard Riou, their drawings being engraved by Henri Hildibrand. See the rest of them here.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The etching and engraving archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

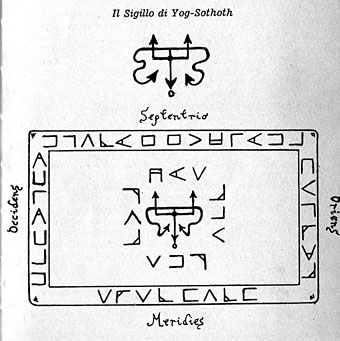

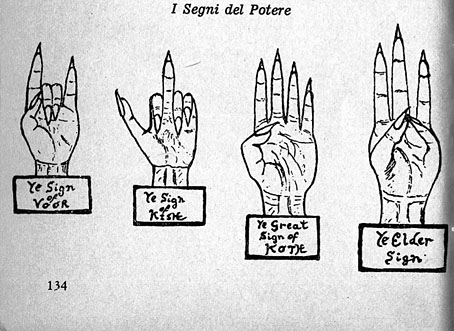

• Eco calls on Cthulhu