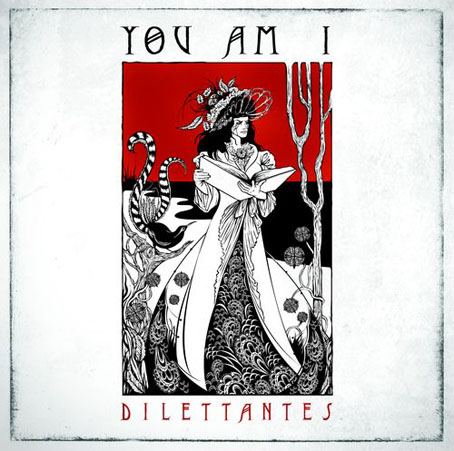

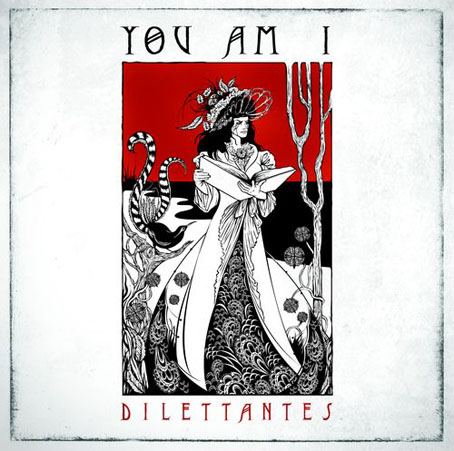

Dilettantes by You Am I (2008). Illustration and design by Ken Taylor.

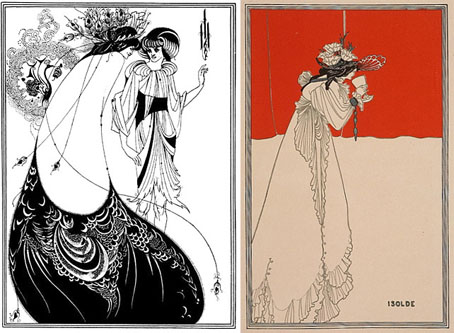

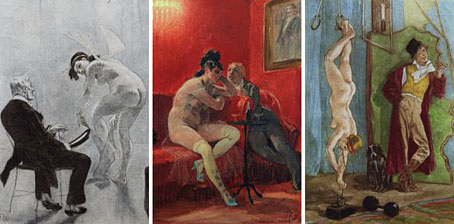

Dilettantes is the eighth studio album from Australian band You Am I which is released this week sporting a very creditable Beardsley pastiche by illustrator Ken Taylor. Sleevage has more details about the creation of the CD package, including preliminary sketches. Those familiar with Beardsley’s work may see in the cover drawing references to The Peacock Skirt and the colour print of Isolde. I like the way Beardsley’s peacock has been exchanged for a more suitably antipodean lyrebird. This isn’t Beardsley’s only influence in the musical world, of course. A few more examples follow.

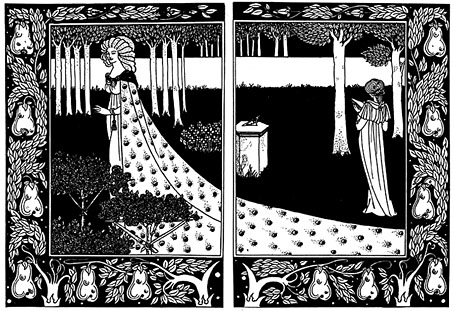

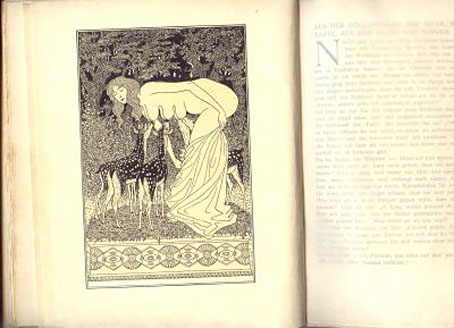

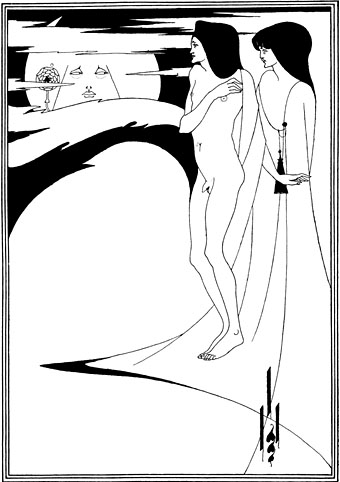

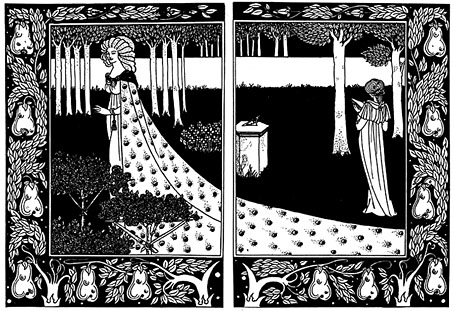

left: The Peacock Skirt from Salomé (1894); right: Isolde (1895).

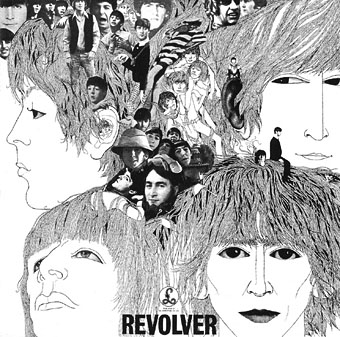

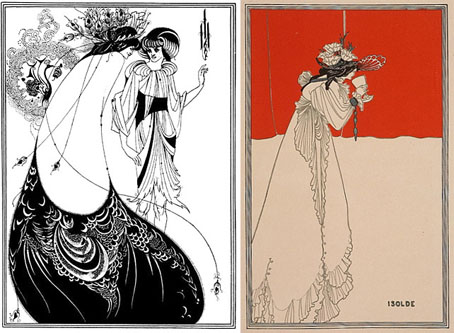

Revolver cover by Klaus Voorman (1966).

The over-familiarity of Klaus Voorman‘s collage/drawing for the cover of Revolver by The Beatles tends to obscure its Beardsley influence but that influence is certainly present in the stylised faces, the figure details and the rendering of the hair. The Beatles themselves were enthused enough with Aubrey to put his face among the pantheon of “people that we like” on the sleeve of Sgt. Pepper a year later. I’d thought for a while that Voorman might have been inspired by the landmark Beardsley exhibition which ran at the V&A in London from May–September 1966. Some correspondence with Raymond Newman, author of Abracadabra, a book about the album, disabused me of that when Raymond confirmed that Voorman in 1966 had already been a Beardsley enthusiast for a number of years.

As well as being possibly the first Beardsleyesque album cover, I wonder whether this was also the first major album release to drop the name of the artist from the front of the sleeve.

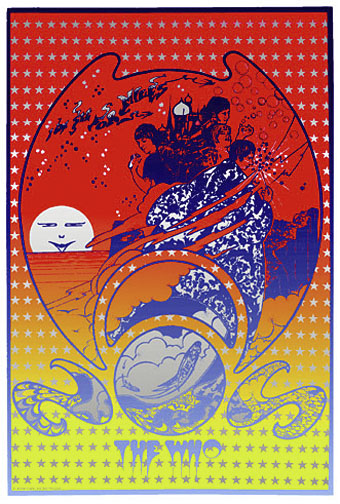

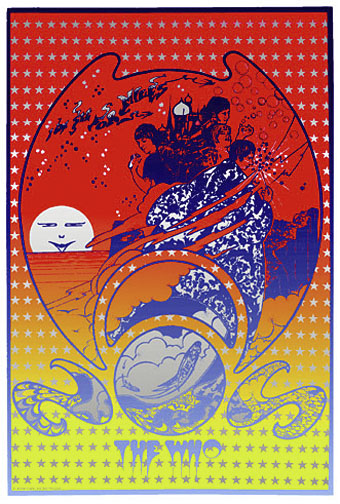

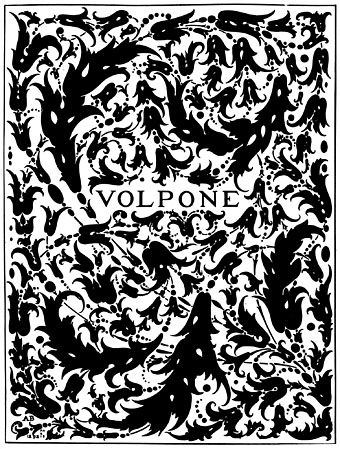

Everyone went psychedelic in 1967, even tough mods like The Who. This Hapshash and the Coloured Coat promo poster for I Can See For Miles (incidentally my favourite Who song) is one of Hapshash’s more overt Beardsley borrowings. The sun (or moon) in the background is a variation on Beardsley’s The Woman in the Moon from Salomé (the face is Oscar Wilde’s) while Pete Townshend’s florid sorcerer’s cloak owes much to Aubrey’s incredible cover design (blocked in gold on the book) for Volpone.

The Woman in the Moon (1894).

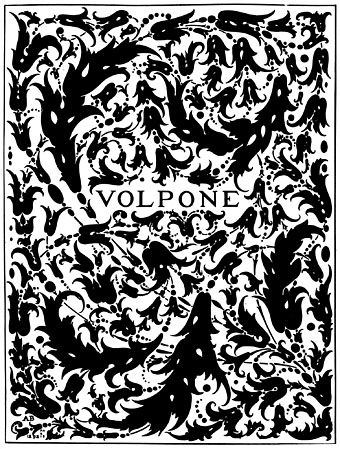

Volpone (1897).

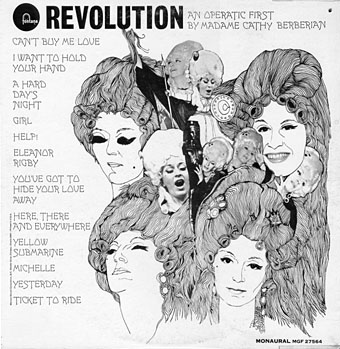

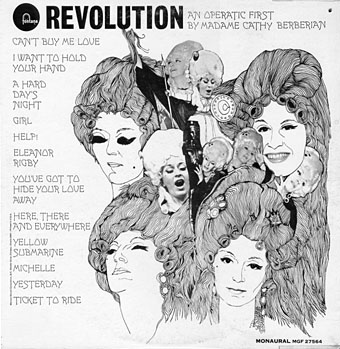

From the sublime to the ridiculous. Cathy Berberian was the mezzo-soprano wife of avant garde composer Luciano Berio, with a long career as a singer of serious classical and contemporary classical works. Her rendition of Berio’s Thema (Omaggio a Joyce)–an electroacoustic setting of the “Sirens” prelude from Ulysses–was one of the tracks on the 1967 electroacoustic compilation Electronic Music III discussed here in April. She also had a separate career as an operatic interpreter of pop music and this collection of Beatles songs dates either from 1968 or 69, depending on which source you choose to believe. Whatever the year, the designer pulled off a decent enough copy of the Revolver sleeve. For a taste of the Berberian style, there’s a sample here. And if you’re desperate for the entire album, this page has a copy.

I’m sure this doesn’t exhaust the Beardsley influence in sleeve design, there must be others between 1968 and 2008. Once again, if you know of any further examples, please leave a comment.

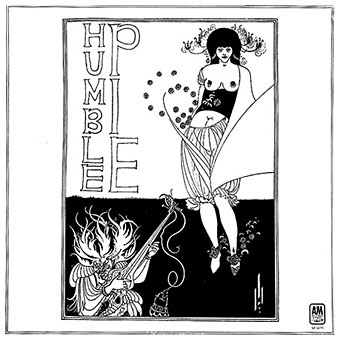

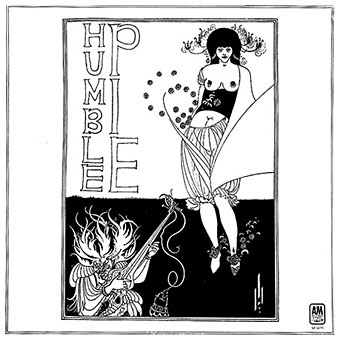

Humble Pie by Humble Pie (1970).

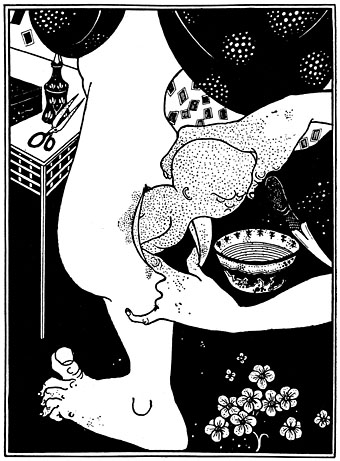

Update: Added Humble Pie’s self-titled third album. The illustration this time is Beardsley’s own, The Stomach Dance from Salomé.

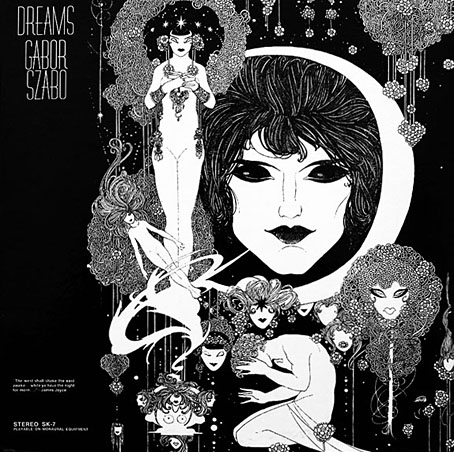

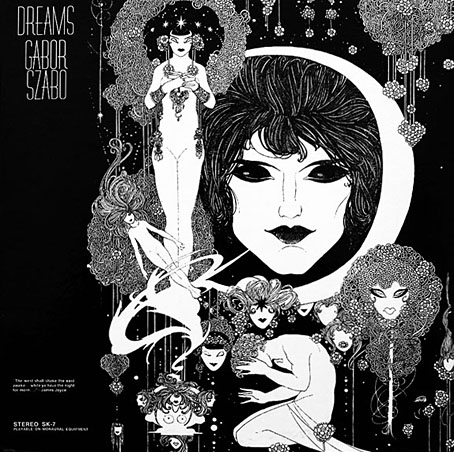

Dreams by Gabor Szabo (1968). Design by David Stahlberg.

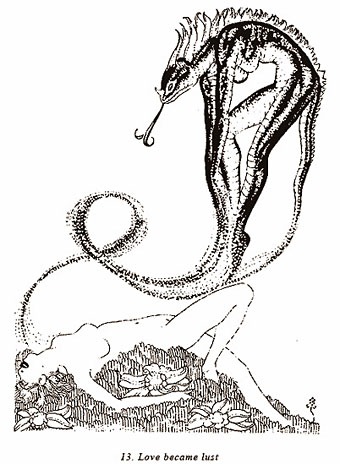

Update 2: Therese discovered this great sleeve for an album by the Hungarian jazz guitarist. Closer in style to John Austen’s illustrations for Hamlet 1922) but Austen’s use of black-and-white at the time was very influenced by Beardsley’s work.

Witchcraft by Witchcraft (2004).

Update 3: Another addition, the debut album from Swedish metal band Witchcraft which uses Beardsley’s Merlin vignette from the Morte Darthur. Thanks to Cyphane for the tip.

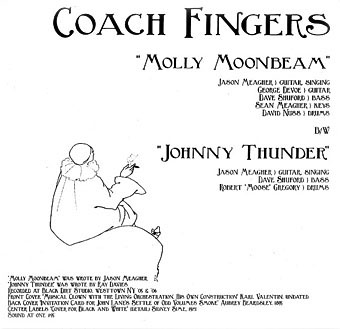

Molly Moonbeam by Coach Fingers (2007).

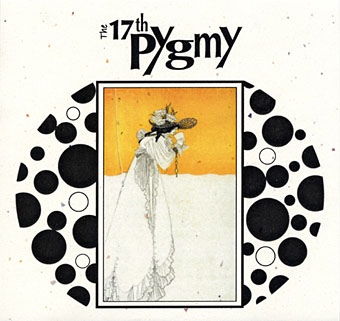

Ballade Of Tristram’s Last Harping by The 17th Pygmy (aka 17 Pygmies) (2007).

Update 4: Added a couple of new discoveries. The 17th Pygmy album apparently includes further Beardsley pieces in its booklet while the Coach Fingers single also has a label featuring designs by Beardsley’s contemporary, Sidney Sime.

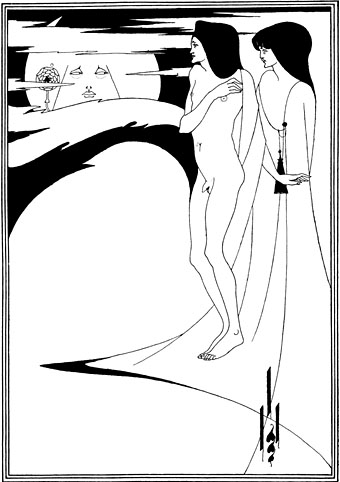

La Beale Isoud at Joyous Gard. (1894).

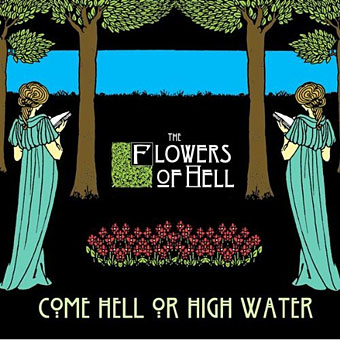

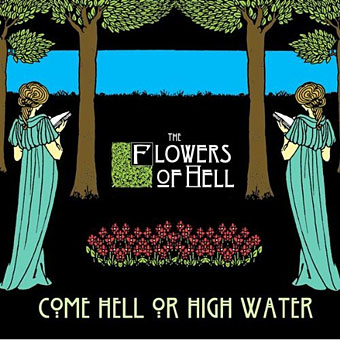

Come Hell Or High Water by The Flowers of Hell (2009).

Update 5: Added the Flowers of Hell cover which is based on La Beale Isoud at Joyous Gard. from Le Morte Darthur. The band also has a video which works variations on the same picture.

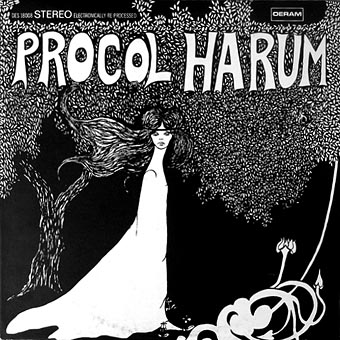

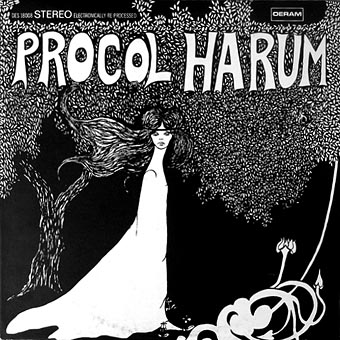

Procol Harum by Procol Harum (1967).

Update 6: Another one I’d missed, Procol Harum’s debut album doesn’t have a credit for the cover art which is perhaps just as well since it doesn’t stand comparison with some of the works above. The same artwork appeared on later reissues when the album was re-titled A Whiter Shade of Pale.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

• The Aubrey Beardsley archive

• The illustrators archive