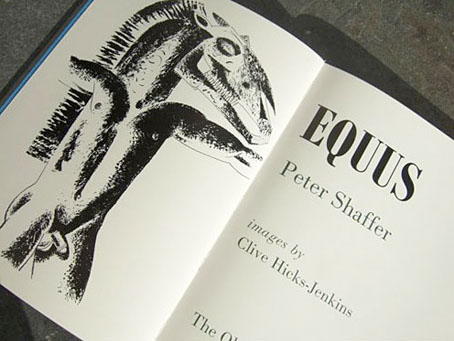

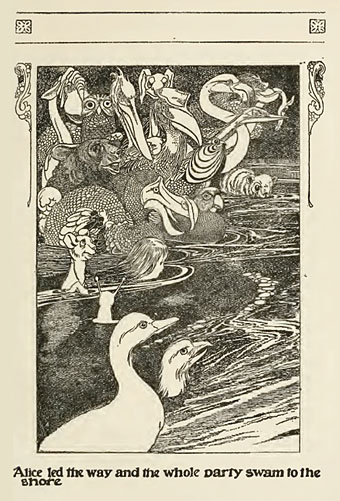

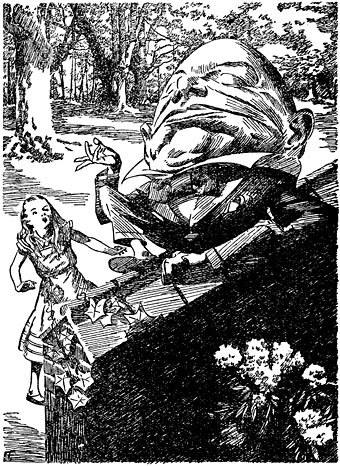

I wrote about Peter Shaffer’s fascinating play, Equus, in September last year, and in passing touched on the horse and Mari Lwyd-inspired paintings of Clive Hicks-Jenkins which seemed to complement the play’s themes of sexuality and passionate obsession. Callum James had been having similar thoughts about Clive’s art and urged his friends at The Old Stile Press to bring play and artist together. Clive was in touch last week to let me know that his illustrated edition of the play is now in print. The Old Stile Press produce limited collectors’ editions of books to the highest standard. Consequently these are expensive works but then they’re as much art pieces as books, as you can see from the care which has been lavished on this particular volume. Nice to see one of my favourite typefaces, Bodoni, used for the text.

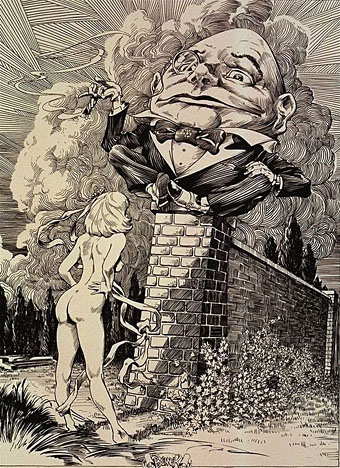

Also in touch last week was photographer Gray Scott with news of this striking picture entitled Executionist which also happens to be a limited edition print. This is another expensive piece—as limited prints tend to be—but there’s no law that says the best things have to be cheap, is there?

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Dark horses

• Gray Scott