Part of the Playstation Season, “a partnership between PlayStation and 5 international public arts institutions renowned for an innovative approach to arts programming — BALTIC, the V&A, ENO, Sadler’s Wells and the BFI.”

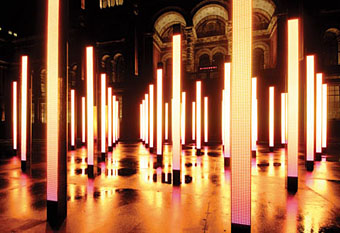

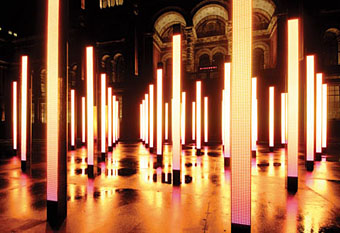

A luminous interactive installation will transform the V&A’s John Madejski Garden this winter. Volume is a sculpture of light and sound, an array of light columns positioned dramatically in the centre of the garden.

Volume responds spectacularly to human movement, creating a series of audio-visual experiences. Step inside and see your actions at play with the energy fields throughout the space, triggering a brilliant display of light and sound.

The piece is a collaboration between lighting designers United Visual Artists (UVA) and Robert Del Naja (alias 3D) of Massive Attack and his long-term co-writer Neil Davidge (as part of their music production company, one point six).

Looks like a cross between Jenny Holzer‘s vertical signs and the Edmond J Safra Fountain Court at Somerset House which I had the opportunity to photograph one gloomy evening back in May (below). And speaking of that square, it’s been turned into an ice rink again for the winter.