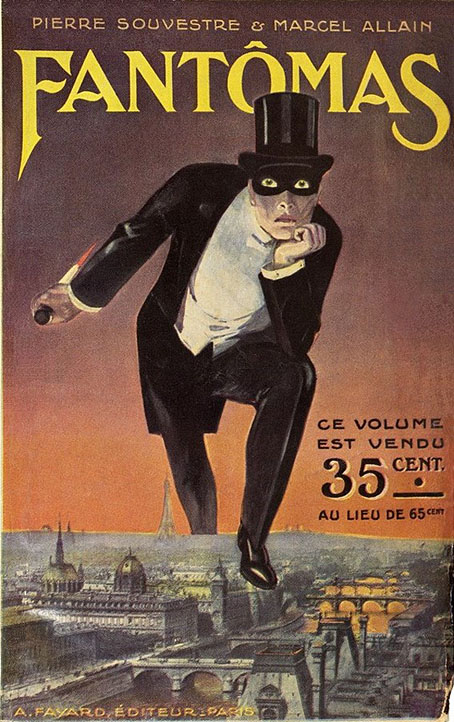

Uncredited cover art for the first publication, 1911.

The post title is a word apparently invented by James Joyce, one whose origin I’ve yet to discover. There may be some slight disparagement in its use of “enfant”, a suggestion that the Fantômas novels (or the films derived from them) were childish pleasures. If so, those childish pleasures had many supporters among the cultural avant-garde of Paris, as we’ll see below.

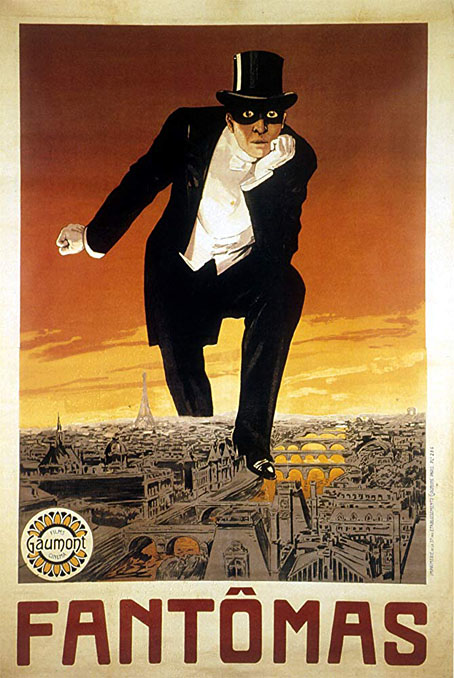

Uncredited poster art, 1913. The blood-stained dagger on the cover of the novel was too much for Gaumont.

This isn’t the first time I’ve written about Fantômas, the master criminal whose exploits thrilled French readers in the years before the First World War. But I’m writing now having finally read a translation of Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre’s first Fantômas novel, and also watched the five Louis Feuillade films which introduced Fantômas to an international audience in 1913 and 1914. The novel was worth reading even though it doesn’t rise much above the pulp fiction of the time; Allain and Souvestre were writing in haste, their books were never going to win any literary awards. Fiction doesn’t have to be finely-crafted in order to capture the popular imagination (look at James Bond…), but Fantômas is unusual for being so popular while also being essentially formless: a persistently elusive criminal mastermind with no substantiated identity that the police can discover, whose prowess with disguise enables him to infiltrate French society at all levels. Criminal masterminds are plentiful in English literature but they’re usually hiding in the background of stories with heroes as the central character, as with Professor Moriarty and Sherlock Holmes. Guy Boothby’s Doctor Nikola has Fantômas-like qualities but he’s a more ambivalent character, less of an outright villain. A closer English comparison might be Fu Manchu whose first appearance in print was in 1912, a year after the literary debut of Fantômas. The rivalry between Fu Manchu and Denis Nayland Smith of Scotland Yard matches the tireless pursuit of Fantômas by Inspector Juve of the Sûreté; yet Fu Manchu still has a personal history and, in the later novels, motivations beyond mere criminality. Nothing is known of Fantômas outside his criminal endeavours. His character is so nebulous that one of the later stories sees Inspector Juve arrested after his superiors have convinced themselves that he must be the real hand behind the Fantômas crimes.

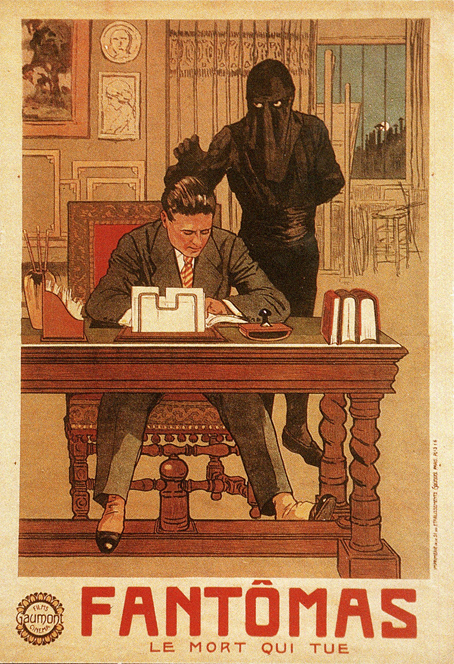

Uncredited poster art, 1913. Fantômas is about to turn his unwitting victim into “The Corpse that Kills”.

On an artistic level the Feuillade adaptations are much more satisfying than their source, even though Fantômas in the films isn’t as triumphantly murderous as he is in the books. After years of only knowing the adaptations from blurred and washed-out stills it’s been a revelation to see the recent Gaumont restorations which have been mastered from the best available prints, cleaned of scratches and other flaws, and projected at the proper speed. The Feuillade serials have circulated for years in inferior copies but I’d always held off watching them in the hopes that better prints might arrive. I’m glad I waited. Cinema was still a young medium in 1913 but Feuillade was a good director, skilled at creating suspense and engineering sudden surprises. He was also working with a decent troupe of actors, especially René Navarre as the villainous leading man. The misconception that early silent acting is all grandiose gestures and exaggerated facial expressions is dispelled in films like these where the acting is generally restrained even when the subject matter is lurid and melodramatic.

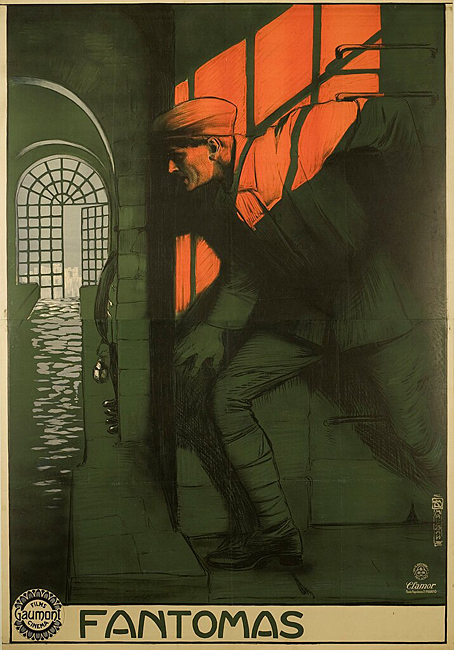

Poster art by Achille Mauzan, 1913.

The UK release of the Feuillade films by Eureka happens to arrive just after 100th anniversary of the first Surrealist Manifesto, a coincidence, no doubt, but a fitting one. The Surrealists enjoyed the “waking dream” quality of the cinema experience, and were especially besotted with Feuillade’s Fantômas serials:

Over the next two decades, Fantômas was championed by the Parisian avant-garde, first by the young poets gathered around Guillaume Apollinaire, who, together with Max Jacob, founded a Société des Amis de Fantômas in 1913, and later by the Surrealists. In July 1914, in the literary review Mercure de France, Apollinaire declared the imaginary richness of Fantômas unparalleled. The same month, in Apollinaire’s own review, Les Soirees de Paris, Maurice Raynal proclaimed Feuillade’s Fantômas saturated with genius. Over the next two decades, poets such as Blaise Cendrars (who called the series “The Aeneid of Modern Times”), Max Jacob, Jean Cocteau, and Robert Desnos, and painters such as Juan Gris, Yves Tanguy, and René Magritte, incorporated Fantômas motifs into their works. Pierre Prévert’s 1928 film, Paris la Belle, featured a Fantômas book cover in the closing sequence, and the Lord of Terror was adapted to the Surrealist screen in Ernest Moerman’s 1936 film short, Mr. Fantômas, Chapitre 280,000. As the century progressed, Fantômas remained a minor source of artistic inspiration as the subject of cultural nostalgia.

Robin Walz from Serial Killings: Fantômas, Feuillade, and the Mass-Culture Genealogy of Surrealism (1996)

All of which has had me searching for examples of the above, some of which I hadn’t seen before. Fantômas was a recurrent source of inspiration for René Magritte yet “the Lord of Terror” is often reduced to a footnote in discussions of Magritte’s career. The appropriation of the name of Fantômas, along with motifs from the novels and films, is a unique moment in art history, one that points the way to the further appropriations of Pop Art and the cultural free-for-all we see in the art world today.

Fantômas (1915) by Juan Gris

Fantômas (1918) by Josef Capek

Fantômas (1925) by Yves Tanguy

Yves Tanguy had only been painting for a couple of years when he was producing pictures like this one. The vague landscapes populated by unidentified objects and organisms didn’t emerge until later.

The Menaced Assassin (1926) by René Magritte

The shot from Fantômas that you see reproduced most often in art books is this one which Magritte remembered when he was painting The Menaced Assassin. The painting isn’t a duplicate but it’s certainly Fantômas-like in its accumulation of suspense, voyeurism, potential ambush, and the aftermath of a violent crime.

Fantômas (1927) by René Magritte

Fantômas appeared on the first book covers and film posters masked while wearing evening dress, but in the films when he’s not heavily disguised he’s more likely to appear as what the intertitles describe as “the Man in Black”, creeping around in a leotard with his head covered like a medieval executioner. His accomplices do the same, and similar outfits may be seen in Feuillade’s follow-up to Fantômas, Les Vampires. Magritte made use of these sinister silhouettes in several drawings and paintings of the 1920s.

The Man from the Sea (1927) by René Magritte

The Female Thief (1927) by René Magritte

La Femme 100 têtes (1929) by Max Ernst

This plate from Max Ernst’s first collage novel bears the title “Fantômas, Dante and Jules Verne”. André Breton also refers to the illustrators of Fantômas in the introduction to the book. (Thanks to Vincent for the reminder!)

Fantomas: Mrtvý, Jenž Zabíjí (1929)

Cover art by Jindrich Styrsky for a Czech translation. Styrsky was one of the first Czech Surrealists.

Monsieur Fantômas (1936)

A short “Film Surrealiste” made by Ernest Moerman in which Jean Michel (Fantômas) and Trudi Van Tonderen (Elvire) enact a series of dramatic scenes, most of which are filmed on a Belgian beach with a handful of props.

René Magritte and The Barbarian

One of the more well-known photo portraits of Magritte, taken in London in 1938. I used to wonder why you seldom saw reproductions of The Barbarian (1927) on its own. The painting was one of many artworks destroyed by fire or bombing during the Second World War.

The Flame Rekindled (1943) by René Magritte

And the loss of Magritte’s painting may explain the title of this later one. Or maybe this refers to the artist rekindling his earlier Fantômastic enthusiasms.

Ballad of Fantômas (1942) by Robert Desnos

A poem performed as a radio broadcast with musical accompaniment.

Écoutez, … Faites silence

La triste énumération

De tous les forfaits sans nom,

Des tortures, des violences

Toujours impunis, hélas!

Du criminel Fantômas…

Continues here with rhyming English translation by Timothy Ades.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Bugs Bunny meets Fantômas in the Aquarium of Love

• The Dark Ledger

Fantômas is also referenced in the penultimate chapter of Max Ernst’s La femme 100 têtes, alongside Dante and Jules Verne — a surrealist namedrop checklist if there ever was one. It’s the collage that ended up on the cover of the Dover paperback.

Great post, with wonderful images and great links. I’ve seen both Fantomas and Les Vampires. I think Fantomas was shown on TCM many years ago…or I may have purchased the discs, but it was a while (20-ish years) back. Now I wonder if I should look into these new releases. It’s hard to keep up with improved versions sometimes- I feel like I was promised the fullest and best “Metropolis” possible at least three (maybe four) different times in the last twenty years.

As a boy in the 60’s and 70’s I remember going to a bodega in Miami, and next to the soda machine by the door there was the comic book display. My mother would park me there so she could shop with a lemon soda and the “library” of Mexico produced comic books: Superman, Turoc and Fantomas.

Yes, great post. I’ve encountered references to Fantômas over the years and looked for a way “in”. This post serves nicely, thanks! And yet another reminder why I invested in a multi-region Blu-Ray player.

Is there a relationship between Fantômas and Dr Mabuse, deeper than just general inspiration?

Vincent: Thanks! I knew there was a Max Ernst reference somewhere but I spent so much time chasing other things I didn’t pursue it even though I have all those books. I’ve added the relevant page.

Jim: The quality of the restorations really makes it worth while> I love watching resotred silent films on blu-ray. And I also have multiple copies of Metropolis!

Federico: Yes, this post is concerned with the books and the early films but Fantômas lives on after them. There were more films in later decades, including the comedy series in the 1960s starring Jean Marais.

Stephen: I think there are already US releases of the Gaumont restorations. It’s taken them a while to turn up here.

I was thinking of rewatching the Fritz Lang Mabuse films as it happens. I think Mabuse is closer to Doctor Nikola since he can hypnotise his victims. And he’s not really as hands-on as Fantômas.

Speaking of French pulp from the early 20th century, “Arsene Lupin, Gentleman-Thief” by Maurice Leblanc (translated by Alexander Teixeira de Mattos) is quite good fun.

Yes, I know Lupin by name but haven’t read anything. I’ve wondered a few times if his surname was responsible for the Monty Python sketch about Dennis Moore, a highwayman who robs the wealthy of their lupins.

Lupin and Fantômas were teamed with Jules Verne’s Robur and Jean de La Hire’s Nyctalope as “Les Hommes Mystérieux” in Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.