Murder, My Sweet.

One of the bonuses of the Big Noir Watch was getting to see just how many dream/nightmare/hallucination sequences there were in the listed films besides those I remembered from previous viewings. The dream sequence is almost as old as cinema itself but the often lurid and melodramatic nature of noir storylines makes dreams and nightmares another recurrent feature of the the landscape. Beleaguered, paranoid characters are liable to find the Expressionist roots of noir cinema lurking behind their closed eyelids, ready to tip them into an unstable world of blurred vortices and looming, underlit faces.

Stranger on the Third Floor.

Production credits referred to these sequences (when they refer to them at all) as montages, a rather confusing term when montage is another word for film editing in general. The sequences were invariably the work of people other than the director, either a montage specialist or a photographer familiar with optical printing and camera effects. Before Don Siegel became a notable noir director he was a montage creator at Warner Brothers; the sequence showing the invasion of France in Casablanca is one of his. He credited his montage work with teaching him all about cinema craft.

The following examples are all the sequences I noticed during the recent noir binge. If you know of any other good ones from the 1940s or 1950s then please leave a comment.

Stranger on the Third Floor (1940)

An aspiring reporter is the key witness at the murder trial of a young man accused of cutting a café owner’s throat and is soon accused of a similar crime himself.

Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward mark the beginning of what they term “the noir cycle” with The Maltese Falcon in 1941. But many other writers choose Stranger on the Third Floor as the beginning of the genre that would dominate the 1940s. With good reason: the film is 60 minutes of non-stop fear and paranoia photographed by Nicholas Musuraca, one of the RKO cinematographers whose use of shadows would help define the noir style. The celebrated dream sequence is almost a film in itself, with huge, shadow-filled sets in which reporter Mike Ward (John McGuire) undergoes accusation, an unwinnable trial and a slow walk to the electric chair.

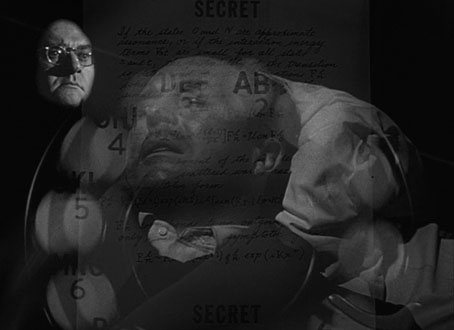

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

After being hired to find an ex-con’s former girlfriend, Philip Marlowe is drawn into a deeply complex web of mystery and deceit.

The first adaptation of Farewell, My Lovely changed the title so that viewers wouldn’t think it was another Dick Powell musical. As with The Big Sleep, the adaptation mangles the plot but it has its plus points, especially Mike Mazurki as Moose Malloy, an ex-wrestler whose performance as the overbearing ex-con is definitive. It also has this great hallucination sequence. In the novel Marlowe is blackjacked by rogue cops then wakes in a mysterious clinic with a head full of drugs. The film takes us inside Marlowe’s head during his unconscious episode, the Surrealist montage sequence being credited to Douglas Travers.

Conflict (1945)

An engineer trapped in an unhappy marriage murders his wife in the hope of marrying her younger sister.

Humphrey Bogart plays the scheming engineer who finds himself besieged by accusatory faces following a serious car crash. The sequence was directed by Roy Davidson with camera work by HF Koenekamp. Bogart’s dream includes repeated shots of swirling water racing down a plug-hole, a cheap vortex effect that reappears in later sequences.

Black Angel (1946)

When Kirk Bennett is convicted of a singer’s murder, his wife tries to prove him innocent…aided by the victim’s ex-husband.

Based on a novel by Cornell Woolrich. One of the great noir villains, Dan Durea, endures another accusatory episode after drinking too much. The “special photography”, most of which involves liquid ripples of one sort or another, was by DS Horsley.

Fear in the Night (1947)

A man dreams he committed murder, then begins to suspect it was real.

Based on a short story, Nightmare, by Cornell Woolrich. Most dream sequences occur somewhere in the middle of a narrative but this film opens in the middle of the nightmare, with DeForest Kelley in his screen debut fighting for his life inside a mirrored room. More like a Twilight Zone episode than a feature film, and rather poorly made compared to the remake (see below). Also very difficult to find in a watchable print.

Odd Man Out (1947)

A wounded Irish nationalist leader attempts to evade police following a failed robbery in Belfast.

After seeing faces talking to him in the beer bubbles spilled across a pub table, James Mason’s delirious fugitive hides out with a crazed painter in whose studio he suffers further hallucinations when the portraits float off the walls to provide an audience for his ravings. As with The Third Man, director Carol Reed showed that the noir idiom could be situated away from the streets of America. Special effects by Stanley Grant and Bill Warrington.

The Big Clock (1948)

A magazine tycoon commits a murder and pins it on an innocent man, who then tries to solve the murder himself.

Another drunken montage, with Ray Milland revisiting the dipsomania he portrayed in The Lost Weekend.

The Dark Past (1948)

An escaped psychopathic killer who takes the family and neighbours of police psychologist hostage reveals a recurring nightmare to the doctor.

A minor cinematic trend of the late 40s/early 50s saw escaped criminals taking people hostage inside their homes. The Desperate Hours is the most famous example but this one came before it, adding Freudian psychology to the drama. William Holden plays the troubled killer whose brainstorm sequence is filmed entirely in greyed-out negative. The umbrella (reminiscent here of Francis Bacon’s Painting) is a clue to his traumatic past.

The Lady from Shanghai (1948)

Fascinated by gorgeous Mrs. Bannister, seaman Michael O’Hara joins a bizarre yachting cruise, and ends up mired in a complex murder plot.

Not quite a dream sequence but very dreamlike in effect, the end of Orson Welles’ film sees his character escaping a trial for murder by swallowing painkillers that eventually knock him out. He wakes to find he’s been concealed from the police in a San Francisco funfair, a place of vast shadows, Expressionist decor (there’s even a nod to The Cabinet of Dr Caligari) and the Magic Mirror Maze where the final showdown takes place.

The Thief (1952)

A chance accident causes a nuclear physicist, who’s selling top secret material to the Russians, to fall under FBI scrutiny and go on the run.

Ray Milland again in one of the oddest films in the entire noir cycle, an espionage drama with no dialogue at all. Milland’s treacherous scientist communicates with Soviet agents via wordless phone calls: they ring three times then he goes to deliver a new document stolen from his workplace. After he kills an FBI agent he suffers a restless night where giant phone dials provide the de rigueur spinning visuals.

The Blue Gardenia (1953)

A telephone operator ends up drunk and at the mercy of a cad in his apartment. The next morning she wakes up with a hangover and the terrible fear she may have committed murder.

Norah (Anne Baxter) slugs a would-be rapist with a poker before swooning into another swirling plug-hole while animated shapes flare in the background. Special effects by Willis Cook.

Nightmare (1956)

A New Orleans musician has a nightmare about killing a man in a strange house but he suspects that it really happened.

A remake by director Maxwell Shane of his earlier Woolrich adaptation, Fear in the Night, with Kevin McCarthy in the lead role. McCarthy is just as frantic here as he was in Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers made in the same year. The nightmare sequence in Fear in the Night had slightly more detail but this one has better picture quality. The special photographic effects are by Howard A. Anderson.

Farewell, My Lovely (1975)

Los Angeles private eye Philip Marlowe is hired by paroled convict Moose Malloy to find his girlfriend Velma, former seedy nightclub dancer.

Dick Richards’ adaptation stays closer to the novel than Murder, My Sweet, with Robert Mitchum a better fit for Marlowe’s trench coat even if he was too old for the role by this point. But Richards makes no attempt to match the delirium of the earlier film’s drug episode, all we get is some sweaty stumbling in the dark while the face of a bullying whorehouse madam guffaws at Marlowe’s predicament. This is a good example of the way in which the dream or hallucination sequence could no longer work in a more realistic presentation unless the director was determined to try something new. After this the best film dreams are either parodies of the form—as in The Big Lebowski—or a part of the texture of the film itself, as in the work of David Lynch or any number of horror films.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Big Noir Book, or 300 films and counting…

• Art on film: Crack-Up

• Art on film: The Dark Corner

• A theme for maniacs

• Invasion revisited

• In the Shadow, a film by Fabrice Mathieu

• Film noir posters

Odd Man Out is an absolute dream of a film throughout, and a brilliant example of non-USA noir. Plus Robert Newton as the crazy artist! Have you seen Obsession (1949)? Newton again in a strange, sweaty, claustrophobic movie.

(And that still from The Blue Gardenia could well be the template for any pulp paperback/B-movie poster!)

I did not expect to get to the end of this one without seeing “Spellbound” listed! Possibly the most famed such sequence of all, by you-know-who. I assume you left it out on purpose, or maybe you just didn’t re-watch it specifically during the “BNW”?

In other news, nice to see Cornell Woolrich coming up so often. I have a book with a big collection of his stories. Interesting man; good writer.

And R.I.P. Robert Towne. Chinatown alone would be a grand legacy for any writer.

Jim: Yes, these were all the ones I happened to be watching. I’ve got Spellbound on blu-ray along with most of Hitchcock’s other films from 1940 on. I like its dream sequences and the score but I’ve always thought the film as a whole was rather glib and mechanical in its pop Freudianism, and not really noir compared to Shadow of a Doubt or The Wrong Man. But then we’re back to those slippery definitions again… Quite a few other Hitchcocks (eg: Saboteur) are borderline cases.

Martin: Yes, RIP. A shame he had to go in this week of all weeks…

An interesting factoid about Robert Towne. Early on he took an acting class taught by Jeff Corey during his blacklist years. His classmates included Roger Corman, Jack Nicholson, Irvin Kershner, and Sally Kellerman. To have been a fly on the wall…

I was also interested to find out he wrote one of the most unusual episodes of the Outer Limits series, “The Chameleon”, which starred a young Robert Duvall as a spy who undergoes genetic alteration to infiltrate the crew of a crashed flying saucer. What makes this episode rise above merely actors in rubber masks was the treatment of the characters of the aliens and the delightfully offbeat ending (which I won’t spoil). This in 1963 on American TV!

Yeah it’s a shame Hollywood didn’t tag Mitchum for Marlowe in the 40s or 50s. He was perfect.

Thanks John. At least three of this list I have not seen. One of the delights of being a noir fan is that there always seem to be ones to discover that got past you.

I didn’t know that about Towne but it connects with his later writing the screenplay for Corman’s Tomb of Ligeia.

I agree about Mitchum being perfect for Marlowe in the 1940s, or even the 50s. He had the ideal combination of physical presence and smart, sexy attitude that Marlowe has in the books.

Multiple sequences in COTTON CLUB could surely be included on this list. These montages were made by FFC’s heir apparent, Giancarlo Coppola and are his only surviving film work. He was decapitated in a drunken boating accident with Griifin O’Neal speeding in the no wake zone after the marina had closed. That’s about as Noir as they come,