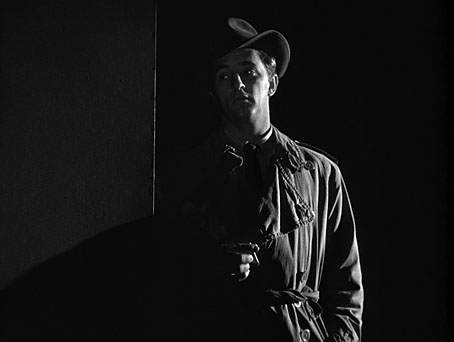

Robert Mitchum in Out of the Past (1947). Photography by Nicholas Musuraca.

“His voice was the elaborately casual voice of the tough guy in pictures. Pictures have made them all like that.” —Raymond Chandler, The Big Sleep

1: The Big Project

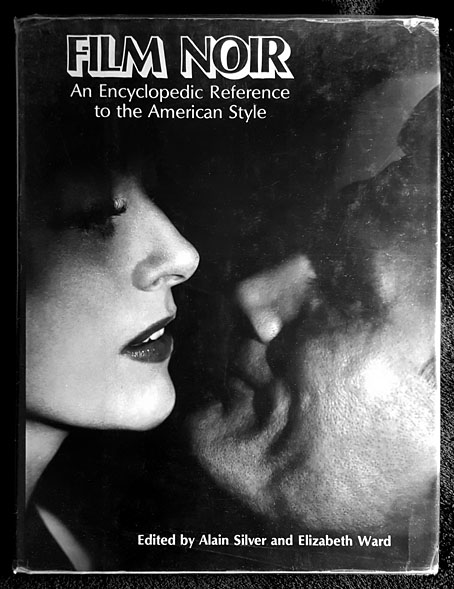

This is a big post about a big subject: the film noir of the 1940s and 1950s, also the “neo-noir” revival of the following decades. The project in question was my attempt to watch all the films listed in a comprehensive study of the form, Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style, which was published in 1979. There are many books about film noir but this one, which I often refer to as The Big Noir Book, is hard to beat, a heavyweight guide in which editors Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward construct a definition of the genre, chart its history, and compile indices for the key creators: actors, writers, directors and cinematographers. The core of the book is a detailed list of 300 films (see below), with production credits for each entry, a précis of each story and a short critical essay.

“Big” is an apposite term; many of these films involve big characters, big passions, big crimes and big predicaments, the latter invariably matters of life or death. The word “big” turns up in a number of noir titles, thanks no doubt to Raymond Chandler’s first Philip Marlowe novel, The Big Sleep. Howard Hawks’ adaptation of the Chandler book is one of the defining films of the genre, one that was very successful despite the plot being rendered incoherent by bowdlerisation and competing screenwriters. The studios spent the next few years offering picture-goers The Big Clock (1948), The Big Night (1951), The Big Heat (1953), The Big Combo (1955) and The Big Knife (1955). Also The Big Carnival (1951), an alternate “big” title for Ace in the Hole.

The big book. On the cover: Joan Crawford and Jack Palance in Sudden Fear (1952).

I can’t be the only person to have encountered Silver & Ward’s list then thought about trying to watch everything on it. But unless you’re an academic or a film reviewer this would have been difficult until very recently, if not impossible when many of the titles are obscure B-pictures that you wouldn’t usually find on TV. The idea first arose in the 1980s when a friend bought a copy of the noir book shortly after I’d been reading Robert P. Kolker’s Cinema of Loneliness, a substantial analysis of five American directors which, in its first edition, includes some discussion of the noir influence on the films of the 1970s. Three of the films that Kolker examines are examples of neo-noir that make the Silver & Ward list: The Long Goodbye, Taxi Driver and Night Moves. Kolker also acknowledges Stanley Kubrick’s grounding in the noir idiom. Kubrick’s Killer’s Kiss and The Killing are both on the list, while the film that followed these, Paths of Glory, features hardboiled dialogue by Jim Thompson, and a cast filled with noir actors. My growing interest in the genre happened to coincide with the arrival on British television of Channel 4, a TV station which spent its early years filling the afternoons and late evenings with re-runs of old films. Silver & Ward’s book had the effect of making me pay closer attention to films I might otherwise have ignored or only watched if there was nothing else on. The book also contextualised these films in a way that’s never required with other genres. This period was an introduction to noir as it really is, as opposed to the clichés which still surround the genre today.

Claire Trevor in Raw Deal (1948). Photography by John Alton.

2: The Big Definition

Everyone knows the noir clichés: private eyes, duplicitous dames, lethal hoods, nightclub singers, sardonic voiceovers, light slanting through venetian blinds, the American metropolis, rain-washed nocturnal streets, big cars, big hats, trench coats, guns, cops, more cops, etc, etc.

Hollywood films of the 1940s do, of course, feature all of these things many times over, but the genre definition offered by Silver & Ward is as much about a pessimistic world-view as it is about the aesthetics of life in the American city. The “noir” quality that French critics of the 1950s identified in post-war American cinema was a visual attribute before it was anything else, a realisation that many of the recent Hollywood films were saturated with angled shadows and endless night. But the black (or, more properly, dark) character of these films is as much a set of circumstances as it is a visual style, one where the wheel of fate is often the most important element driving the story. The visual style can contribute a great deal to the storytelling and the overall mood but noir circumstance can exist, as it does in Leave Her to Heaven, in bright Technicolor sunlight miles away from any city. Fate may manifest as blind chance—mistaken identity, someone in the wrong place at the wrong time—or a deterministic inevitability that leads a protagonist to their destruction. A doom-laden finale was frequently imposed by Hollywood’s Production Code which insisted that crime can never be shown to pay, but the Code’s moral stricture is only obtrusive in the films about criminals. Many noir situations concern ordinary people whose attempts to live decent lives are thwarted by bad decisions or unfortunate circumstance. Despite Hollywood’s reputation for happy endings a negative resolution is a noir staple, as is an atmosphere of desperation, entrapment and paranoia; a Pyrrhic victory is often as good as it gets. Meanwhile, the shadow of war hangs over all the films of the 1940s. Many of the wartime pictures refer in passing to events in Europe, while the post-war films are often informed by the recent ordeals of returned veterans. There’s even a sub-class of noir involving veterans with damaged brains whose amnesias or violent mood swings lead them into trouble.

The noir stereotype of the private eye is well-founded when Silver & Ward mark the beginning of the genre with Humphrey Bogart’s appearance as Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon. Many films about private eyes followed Bogart but not all of them are truly noir, while the genre itself is flexible enough to depart from the detective formula. Film noir doesn’t have to involve cities at all: a number of the films on Silver & Ward’s list are entirely set in small towns or remote rural areas. The genre doesn’t have to be set in the USA either: there are London noirs, South American noirs, Caribbean noirs, European noirs and Far East noirs. The films aren’t always black-and-white or filled with shadows: several of the noirs from the 1950s are in colour, as are all the ones from the 1970s.

Richard Basehart in He Walked By Night (1949). Photography by John Alton.

3: The Big List

The idea of watching all of the films on the list returned a few years ago when I yielded to an urge and finally bought myself a copy of The Big Noir Book. Since 1979 Silver & Ward’s study has been reprinted several times in updated editions but I found a relatively cheap first edition on eBay which I was surprised to discover had been part of the personal library of the late Nick Roddick (the listing didn’t mention this), a film writer whose columns I used to read in Sight and Sound. I think “Mr Busy”, as he styled himself, might have been pleased that at least one of his books went to a good home. Shortly after this, and in quick succession, my local charity shop turned up blu-rays of The Maltese Falcon and The Killers. Watching these films again, then reading what Silver and co. had to say about each of them, impelled me to look for more titles.

What follows is the list of films that Silver, Ward and the book’s other contributors regard as best representing the genre in its many guises. The “noir cycle” as they call it, runs from The Maltese Falcon in 1941 to Touch of Evil in 1958, although the list overlaps these dates. The entries prior to 1941 are significant for being early examples of themes or stylistic qualities that would become more prominent in the years that followed. The genre had run out of steam by the early 1960s but it returned with a vengeance in 1967 with John Boorman’s extraordinary Point Blank, a film that revitalised the presentation of noir’s stock scenarios with techniques informed by European cinema.

How many of these films have you seen?

Abandoned (1949), The Accused (1949), Act of Violence (1949), Among the Living (1941), Angel Face (1953), Appointment with Danger (1951), Armored Car Robbery (1950), The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

Baby Face Nelson (1957), Beast of the City (1932), The Beat Generation (1959), Behind Locked Doors (1948), Berlin Express (1948), Between Midnight and Dawn (1950), Beware, My Lovely (1952), Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), Beyond the Forest (1949), The Big Carnival (aka Ace in the Hole) (1951), The Big Clock (1948), The Big Combo (1955), The Big Heat (1953), The Big Knife (1955), The Big Night (1951), The Big Sleep (1946), Black Angel (1946), Blast of Silence (1961), The Blue Dahlia (1946), The Blue Gardenia (1953), Body and Soul (1947), Border Incident (1949), Born to Kill (1947), Brainstorm (1965), The Brasher Doubloon (1947), The Breaking Point (1950), The Bribe (1949), The Brothers Rico (1957), Brute Force (1947), The Burglar (1957)

Caged (1950), Calcutta (1947), Call Northside 777 (1948), Canon City (1948), Cape Fear (1962), The Captive City (1952), Caught (1949), Cause for Alarm! (1951), The Chase (1946), Chicago Deadline (1949), Chinatown (1974), Christmas Holiday (1944), City Streets (1931), City That Never Sleeps (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Conflict (1945), Convicted (1950), Cornered (1945), Crack-up (1946), Crime of Passion (1957), Crime Wave (1954), The Crimson Kimono (1959), Criss Cross (1949), The Crooked Way (1949), Crossfire (1947), Cry Danger (1951), Cry of the City (1948)

D.O.A. (1950), The Damned Don’t Cry (1950), Danger Signal (1945), Dark City (1950), The Dark Corner (1946), The Dark Mirror (1946), Dark Passage (1947), The Dark Past (1948), Dead Reckoning (1947), Deadline at Dawn (1946), Decoy (1946), Desperate (1947), Destination Murder (1950), Detective Story (1951), Detour (1945), Dirty Harry (1971), Double Indemnity (1944), A Double Life (1947), Drive a Crooked Road (1954)

Edge of Doom (1950), The Enforcer (1951), Experiment in Terror (1962)

Fall Guy (1947), Fallen Angel (1946), Farewell, My Lovely (1975), Fear (1946), Fear in the Night (1947), The File on Thelma Jordan (1950), Follow Me Quietly (1949), Force of Evil (1948), Framed (1947), The French Connection (1971), The French Connection II (1975), The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), Fury (1936)

The Gangster (1947), The Garment Jungle (1957), Gilda (1946), The Glass Key (1942), The Guilty (1947), Guilty Bystander (1950), Gun Crazy (1950)

The Harder They Fall (1956), He Ran All the Way (1951), He Walked by Night (1949), Hell’s Island (1955), Hickey & Boggs (1972), High Sierra (1941), High Wall (1947), His Kind of Woman (1951), The Hitch-Hiker (1953), Hollow Triumph (1948), House of Bamboo (1955), House of Strangers (1949), House on 92nd Street (1945), The House on Telegraph Hill (1951), Human Desire (1954), Hustle (1975)

I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), I Died a Thousand Times (1955), I, The Jury (1953), I Wake Up Screaming (1942), I Walk Alone (1948), I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951), I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes (1948), In a Lonely Place (1950)

Johnny Angel (1945), Johnny Eager (1942), Johnny O’Clock (1947), Journey into Fear (1943)

Kansas City Confidential (1952), Key Largo (1948), The Killer is Loose (1956), The Killer that Stalked New York (1951), The Killers (1946), Killer’s Kiss (1955), The Killing (1956), Kiss Me Deadly (1955), Kiss of Death (1947), Kiss the Blood off my Hands (1948), Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye (1950), Knock on Any Door (1949), The Kremlin Letter (1970)

The Lady from Shanghai (1948), Lady in the Lake (1947), Lady on a Train (1945), A Lady Without Passport (1950), Laura (1944), Leave Her to Heaven (1945), The Letter (1940), The Lineup (1958), Loan Shark (1952), The Locket (1947), The Long Goodbye (1973), The Long Wait (1954), Loophole (1954)

M (1951), Macao (1952), Madigan (1968), The Maltese Falcon (1941), The Man Who Cheated Himself (1951), The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Manhandled (1949), Marlowe (1969), The Mask of Dimitrios (1944), Mildred Pierce (1945), Ministry of Fear (1945), Mr Arkadin (1955), The Mob (1951), Moonrise (1949), Murder is My Beat (1955), Murder, My Sweet (1944), My Name is Julia Ross (1945), Mystery Street (1950)

The Naked City (1948), The Naked Kiss (1964), The Narrow Margin (1952), New York Confidential (1955), Niagara (1953), The Nickel Ride (1975), Night and the City (1950), Night Editor (1946), The Night has a Thousand Eyes (1948), The Night Holds Terror (1955), Night Moves (1975), Nightfall (1957), The Night Runner (1957), Nightmare (1956), Nightmare Alley (1947), 99 River Street (1953), Nobody Lives Forever (1946), Nocturne (1946), Nora Prentiss (1947), Notorious (1946)

Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), On Dangerous Ground (1952), The Other Woman (1954), Out of the Past (1947), The Outfit (1973)

Panic in the Streets (1950), Party Girl (1958), The People Against O’Hara (1951), Phantom Lady (1944), Pickup on South Street (1953), The Pitfall (1948), Plunder Road (1957), Point Blank (1967), Possessed (1947), The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), The Pretender (1947), Private Hell 36 (1954), The Prowler (1951), Pushover (1954)

The Racket (1928), The Racket (1951), Railroaded! (1947), Raw Deal (1948), The Reckless Moment (1949), Red Light (1950), Ride the Pink Horse (1947), Roadblock (1951), Road House (1948), Rogue Cop (1954)

Scandal Sheet (1952), Scarlet Street (1945), Scene of the Crime (1949), The Scoundrel (1935), The Second Woman (1951), The Set-Up (1949), 711 Ocean Drive (1950), Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Shakedown (1950), The Shanghai Gesture (1941), Shield For Murder (1954), Side Street (1950), Sleep, My Love (1949), The Sleeping City (1950), Slightly Scarlet (1956), The Sniper (1952), So Dark the Night (1946), Somewhere in the Night (1946), Sorry, Wrong Number (1949), Southside 1-1000 (1950), The Split (1968), Storm Fear (1956), Strange Illusion (1945), The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946), The Stranger (1946), Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), Strangers on a Train (1951), Street of Chance (1942), The Street With No Name (1948), The Strip (1951), Sudden Fear (1952), Suddenly (1954), Sunset Boulevard (1950), Suspense (1946), Sweet Smell of Success (1957)

T-Men (1948), Talk About a Stranger (1952), The Tattered Dress (1957), The Tattooed Stranger (1950), Taxi Driver (1975), Tension (1950), They Live By Night (1948), They Won’t Believe Me (1947), The Thief (1952), Thieves’ Highway (1949), The Thirteenth Letter (1951), This Gun For Hire (1942), Thunderbolt (1929), Too Late For Tears (1949), Touch of Evil (1958), Try and Get Me (aka The Sound of Fury) (1950), The Turning Point (1952)

Uncle Harry (aka The Strange World of Uncle Harry) (1945), The Undercover Man (1949), Undercurrent (1946), Underworld (1927), Underworld USA (1961), Union Station (1950), The Unknown Man (1951), The Unsuspected (1947), Vicki (1953)

When Strangers Marry) (aka Betrayed) (1944), Where Danger Lives (1950), Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950), While the City Sleeps (1956), White Heat (1949), The Window (1949), Witness to Murder (1954), The Woman in the Window (1945), Woman on the Run (1950), World for Ransom (1954), The Wrong Man (1956), You Only Live Once (1937)

It’s taken me almost two years to work through this list; I started in August 2022 and finished last week. I’ve dutifully watched everything with the exception of the three earliest films, Underworld (1927), The Racket (1928) and Thunderbolt (1929), all of which are listed for being notable precursors. (The Racket from 1951—which I did watch—is a remake of the earlier film.) Looking back over the list I’d have trouble saying what happens in some of the more obscure entries without reading descriptions. Those vague and unmemorable one-word titles can be shuffled around to chart the progress of a noir narrative: Tension, Suspense, Fear, Conflict, Desperate, Cornered, Caught, Convicted. While tracking down the more elusive pictures I was also re-watching a handful of films that aren’t on the list: Odd Man Out (1947), Split Second (1953), Rififi (1955), Klute (1971), The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976), The Driver (1978), Cutter’s Way (1981), Thief (1981), Hammett (1982), Blood Simple (1984), The Last Seduction (1994) and A Simple Plan (1998).

Many of the listed films are currently available on disc but most of the ones I watched were downloads of some sort. The Internet Archive now has a Film Noir section which was very useful, although quality there is often lacking, and some of the better prints are only available with burned-in Spanish subtitles. People who do this belong in the Big House. A few of the films are so neglected they’ve been difficult to find at all. A recurrent frustration was discovering that films which are now in the public domain aren’t always available as decent prints. Being free for everybody seems to dissuade anyone from doing a proper restoration job. I struggled through a handful of titles that were old dupe prints with poor sound and missing frames. Artistic quality, on the other hand, was surprisingly high considering the list is so long. I think there were only around ten or twelve films that I thought especially bad but I watched them all the same. Worst of the lot, and a film I’ll be happy to never see again, was The Other Woman, one of several melodramas written, directed, produced and starring Hugo Haas. If you ever decide to work your own way through Silver & Ward’s list then save Mr Haas and his other woman for last.

T-Men (1947). Photography by John Alton.

As for the best films, there are too many to mention. One of the great pleasures of this endeavour was being surprised on a regular basis by films I might never have seen without having had my viewing programmed in this manner. I carefully avoided reading any of the critical pieces in the noir book before watching each film, mainly to avoid spoilers, but I also enjoyed knowing next to nothing about each film before it began. I’ve been impressed by directors and actors that I’ve paid little attention to in the past. Richard Conte was among the latter. After watching him for years as the sinister Don Barzini in The Godfather it was good to finally see him at the peak of his popularity, and in roles which anticipate his Godfather appearance.

I’ve not seen any of Silver & Ward’s updated lists but I believe they may have added more of the neo-noir titles from the 70s and 80s. This is a tricky area since neo-noir is the place where the genre becomes even more self-conscious than it was already. The best noir films of the 1970s are those that develop the genre or comment upon it in some way rather than simply adopting its surface characteristics. The Long Goodbye, for example, is a much more interesting adaptation of a Philip Marlowe novel than the period retread of Farewell, My Lovely. Neo-noir at its best pursues the themes of fatalism and entrapment without wheeling out the stylistic cliches. The 1970s was a decade especially suited to this sensibility, as Robert P. Kolker noted in 1980: “Feelings of powerlessness in our daily lives have become realised in our recent film with images and themes of paranoia and isolation stronger than forties film noir could have managed.”

Brian Donlevy, Richard Conte and Cornel Wilde in The Big Combo (1955). Photography by John Alton.

4: The Big Lesson

Things I learned in the two years I’ve spent watching these films:

• Any noir starring the following is worth watching: Dana Andrews, Humphrey Bogart, Lee J. Cobb, William Conrad, Richard Conte, Joan Crawford, Kirk Douglas, Dan Durea, Glenn Ford, John Garfield, Gloria Graham, Farley Granger, Sterling Hayden, Van Heflin, William Holden, Alan Ladd, Burt Lancaster, Ida Lupino, Robert Mitchum, Edmond O’Brien, Jack Palance, Edward G. Robinson, Robert Ryan, George Sanders, Lizabeth Scott, Barbara Stanwyck, Gene Tierney, Claire Trevor, Richard Widmark, Shelley Winters. If the film stars two or more of these actors then you’re onto a winner.

• Raymond Burr played a lot of heavies.

• Ellen Corby played a lot of maids and cleaning ladies.

• George Raft was as wooden as his surname.

• A few actors make very early appearances in these films then turn up later as major players. Edmond O’Brien is in so many of the listed films that he runs the gamut of noir characters: good cop, crooked cop, insurance detective, crime boss, crime victim, state prosecutor, doomed man, etc.

• Noir was flexible enough to allow actors known for other types of films to try something new. One of the oddest entries on the list is Christmas Holiday, a film whose title and cast (Gene Kelly and Deanna Durbin) suggests a musical comedy. Far from it: Kelly plays a mentally unbalanced man who ends up in jail for murder, leaving his estranged wife (Durbin in her first adult role) earning a living as a hostess and singer in a seedy New Orleans bar.

• Any film that’s photographed by John Alton is worth watching, regardless of the cast.

• The Hitch-Hiker is justly celebrated for being a tough picture by one of Hollywood’s few women directors (also a noir star), Ida Lupino. But many of the other films on the list are written by women, if not the screenplays then the stories those screenplays were based on.

• Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain are often regarded as the godfathers of noir but Cornell Woolrich beats them all where this list is concerned. Eleven of the films are based on Woolrich novels or stories.

• Noir films are generally regarded as formulaic, and many of them are, but generic restraints often lead to formal invention. Gun Crazy features a scene in which a bank robbery is filmed on location from start to finish in one long take with the camera in the back of a car; The Lady in the Lake is filmed entirely from the point-of-view of Robert Montgomery as Philip Marlowe; The Set-Up takes place in real time, beginning and ending with views of a ticking clock; The Thief is a film without any dialog at all.

• Crime is a common noir subject which means that money is a predominant concern. But what was it worth in the 1940s and 50s? If someone mentions a figure I usually add a mental zero to the number for contemporary scale.

• Gangland terms such as “contract killing” and “hit” were introduced to American cinema by The Enforcer in 1951. Other films of the early 1950s present the first discussion of nationwide crime syndicates. By the end of the decade all of this is taken for granted and doesn’t require explaining to an audience.

• Several of the films feature urban car chases years before Robbery and Bullitt.

• New York and Los Angeles are the primary noir cities but San Francisco is also a common location.

• The Art Deco tower of Los Angeles City Hall gets to be a very familiar sight in these films. So familiar it may be the building that appears more than any other in the noir cycle.

• Other recurrent LA locations are Union Station (one of the films on the list is even set there), the Angel’s Flight funicular railway, and the steep streets and wooden buildings of the old Bunker Hill district. Raymond Chandler in The High Window describes Bunker Hill as “old town, lost town, shabby town, crook town.” The dilapidated buildings were demolished years ago but many of these films give you a view of the area as it was in the 1940s.

• I don’t like films set in prison very much but I was impressed by Caged—about the corrupting nature of a women’s prison—and the shockingly bleak and nihilistic Brute Force.

• And I don’t like boxing pictures very much but I was happy to re-watch Body and Soul—the archetypal rags-to-riches-to-corrupted-loser boxing picture—and The Set-Up, the directorial debut of Robert Wise.

So after all this effort am I done with the genre? I don’t think so, in fact I’m looking forward to watching many of the new discoveries again. There were a few occasions when I felt distinctly noir’d out, and didn’t want to spend another evening watching ill-fated men and women walking the mean streets of post-war America. But the pleasure of discovery was a real thrill which kept me going and makes me want to see more. Long as it is, the Silver & Ward list contains a good percentage of the films which can be called noir, but a more complete list might run to 400 films or more. The peak of the genre coincided with a period of over-production in Hollywood, which is why you can find 24 films on the list released in 1946 alone. And the genre boundaries are so fluid that it’s a matter of taste (or definition) as to what gets classed as truly noir. Silver & Ward address this question at the end of their book, with a discussion of marginal cases and generic hybrids such as noir westerns (Blood on the Moon), noir horror (Cat People), period films (The Spiral Staircase) and comedies (Unfaithfully Yours). No mention is made of science fiction but there are a few examples to be found. Robert Wise was a significant noir director, and the genre was still thriving in 1951 when he made The Day the Earth Stood Still, a film replete with shadow-filled visuals, fear and suspicion, an apocalyptic storyline, a Bernard Herrmann score and a cast of noir actors. Five years later another noir director, Don Siegel, was making Invasion of the Body Snatchers, a film that puts an SF twist on the typical noir concerns of paranoia, entrapment and desperate flight. By the 1980s the neo-noir trend of the previous decade had leaked into Blade Runner and The Terminator, while cyberpunk literature was energising the SF genre with a hardboiled prose style that harked back to the days of Dashiell Hammett and Black Mask magazine. Film noir deals with elementary passions and predicaments that have no sell-by date, whatever the world may look like outside the window. The future has been, and will continue to be, a dark one.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Art on film: Crack-Up

• Art on film: The Dark Corner

• Invasion revisited

• In the Shadow, a film by Fabrice Mathieu

• Film noir posters

Wot, no Shock Corridor?

I’ll say this once since any time you make a cultural list of any kind someone immediately pops up to say “You missed X…”:

It’s not my list. There are many things on it that I’d happily replace with better films that they didn’t mention. All complaints about missing favourites should be addressed to the editors of the book.

As for Sam Fuller, he’s well-represented with Pickup on South Street, House of Bamboo, The Crimson Kimono, Underworld U.S.A. and The Naked Kiss.

Once again there must be higher forces at work since since one my absolute favorites, Act of Violence was just this week released on Region A NTSC Blu-Ray here in the states. Up to now it had only been available as part of a twofer on a DVD with a mediocre print. Van Heflin, Robert Ryan, an impossibly young Janet Leigh, Mary Astor as the whore with the heart of gold, dark secrets, revenge, obsession, what more do you want!

John if you’re still up for a prison type noir watch Crashout from 1955. It stars William Bendix, Arthur Kennedy, and William Talman (doing one of his classic 50s psychos) as part of a band of escaped convicts journeying to retrieve the loot, one step ahead of the cops (led by good old Morris Ankrum). What makes the picture though are all the supporting characters they encounter on their “quest”. The movie opens with an astounding – and brutal – breakout sequence. And never looks back. The classic one way trip. It’s on YouTube.

I think you’re on the right track as far as defining the genre. True unadulterated noir does not take place in a Christian universe. Redemption is impossible. We’re almost back to the classical Greeks. What horrified them about the story of Oedipus was watching the fates grind him down.

Many, many thanks for penning this enthusiastic and fascinating article, John, which arrives at the moment I’ve just finished reading The Fade Out by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips (which in turn reminded me somewhat of Robin Robertson’s The Long Take). A monumental task! Congratulations! I shall never view all of the films mentioned but, for now, I remember the precision mechanics of The Set-Up, the astounding sight of a someone running down a tunnel with a flashlight (The Big Combo? The T-Men?) and the technicolour nastiness of Leave Her To Heaven (which I watched after John Waters mentioned it as a favourite). And then there’s Detour, Kiss Me Deadly, Nightmare Alley… ah, there’s always one more dark street around the bend. And you could probably write an entire book on the Bradbury Building. Keep up the great work!

In the summer weather, if the sun is shining, I develop a passion for ”neon-noir”, with films such as DRIVE, COLLATERAL, UNDER THE SILVER LAKE, and GOOD TIME occupying my mental chambers, alongside listening to Miles Davis and synthwave music. My tastes tend to be rather seasonal, and I know that I am not alone in this regard

Great post, thank you. I can’t resist a film list and this is particularly irresistible. At first glance, I’ve seen 37 of these, which is pitiful. I MUST have seen more than that! I’ve definitely seen Christmas Holiday, though, which is really quite remarkable – Gene Kelly should have played more of those types of role. Anyway, I’ve got some catching up to do!

Nice article! I don’t know how many of these films I’ve watched. I’ve been a fan of vintage Noir since the early 1980s, catching them when and where I am able. I’ll safely guess I’ve seen over a hundred of them; probably closer to two hundred. But that’s over a forty+ year viewing period. I’m afraid they would all run together in my mind if I watched them on the two-year schedule that you did.

I did have to smile when I saw that your least admired film was a Hugo Haas film that I quite enjoyed; de gustibus, though, eh? But then I have a fascination with Cleo Moore’s “acting”. There are actually a few Hugo Haas cultists running around in relative freedom. I confess to a mini quest to see all his oeuvre.

I have always been a bit ambivalent about “neo-noir(s)”. Sometimes it works; sometimes it doesn’t. It’s hard to recapture the earnestness of the originals. The “neo” variety can feel forced or too freighted with irony.

What was the “best” noir? I’d love to pick something with Bogart in it, but I might be forced to say “Double Indemnity”. What a film! In spite of the uncontroversial nature of picking that as one of, if not the top films, I will also offer that I particularly enjoy finding lesser-known little gems. I have a book called “Death on the Cheap: The Lost B Movies of Film Noir” that helped me find a couple of things I hadn’t already seen.

Thank you for this very interesting post John, a great read.

I’ve also been on a bit of an intermittent noir marathon over the past few years, so can relate to / agree with most of your observations.

Trying to define where ‘noir’ begins or ends is always a nightmare, I think everyone on earth has their own take on it… personally I like to think of it less as a genre, and more like an aesthetic virus or fungi, which infects films (or other media) to a greater or lesser extent, sometimes consuming them completely, other times just lurking in the background, or taking over a few scenes or elements here and there. (‘Mildred Pierce’ is a good example – the opening 20 minutes or so is absolute peak noir, but it then heads off in a very different direction for much of the remaining run-time…)

Paradoxically though, I also enjoy trying to disengage noir from the critical / high brow discussion which often surrounds it, and trying to treat the films just as entertaining, production line genre product, much in the same way one would approach lower budget SF or horror films from the same era. That way, you can have a lot of fun just hanging out with one of them of an evening… and then expereince the occasional thrill when it hits way above expectations and slams you sideways.

Sadly I’ve not had the benefit of Silver & Ward’s book (it sounds great), but thank you for sharing their list of titles… out of curiosity/obsessiveness, I just took the liberty of pasting it into a spreadsheet, and have discovered that, to date, I’ve only seen a mere 112 of ‘em… so clearly I still have a lot of catching up to do before I can start struttin’ like a proper noir expert.

Stephen: Act of Violence was one of the ones I hadn’t seen before which I might not have seen otherwise. Robert Ryan is a seriously chilling character in so many of these films, especially Beware, My Lovely (another first-time viewing) where he plays an unpredictable psycho who gets inside Ida Lupino’s home then won’t leave.

I’ve no problem if the characters break out of the prison, just don’t like the films where they’re stuck there for the duration. I’ll look out for Crashout, thanks for the tip!

Martin: Leave Her to Heaven is a Scorsese favourite as well. Kiss Me Deadly and Nightmare Alley are two great favourites of mine. And the Bradbury Building is in more of these films than I realised, it makes me even more pleased I that got to visit the place. We also drove past the City Hall on the way there.

Liam: Collateral is another good slice of noir from Mann but Thief has it beat with its self-destructive ending. As for Refn, one of the films on the list was a Refn restoration (I forget which one). His early Danish films are all very noir-toned, filled with petty criminals and gangsters.

Jim: I can see why Hugo Haas might have some Ed Wood-like cult value but all I could think was “What the hell is this tripe?”

I was very tempted to try and compile a list of ten favourites but I’m never happy doing this, especially when my favourites in any medium often change from one year to the next. I also think it’s impossible to pick a single representative film, the field is too diverse. Some of the best ones confound any attempt to define the genre with a list of essential ingredients: Night and the City is a good example, a great film yet it’s set entirely in London. Double Indemnity would be a great pick, however.

Ben: The big book is a critical study but I was much more concerned with being entertained before anything else when watching these films. Its great fun to pick a film at random without knowing anything about it then be bowled over by its quality. It was only after watching each film that I’d look again to see what S&W had to say about it. The interesting part about this was finding that I disagreed with many of their choices or opinions. This also exposed a few errors in the writing where they’d evidently misremembered plot details.

Genre definitions are always the subject of debate if they’re not tied to a historical period; I’ve read many discussions about what constitutes fantasy, science fiction or horror. I also enjoy hybrid things so I don’t worry too much about permeable boundaries. I recall one time when Ramsey Campbell put Taxi Driver on a list of his favourite horror films. Meanwhile Kiss Me Deadly often gets classed as science fiction because of the way it slips into nuclear weirdness at the end.

Murder by Contract is my favourite on Indicator’s Columbia Noir box sets. A remarkably bleak and stylish film which is one of Martin Scorsese’s favourites.

Another rather oddball little noir that I always recommend is Three Strangersfrom 1946 starring Peter Lorre, Sydney Greenstreet, and Geraldine Fitzgerald. Directed by Jean Negulesco. Photographed by Arthur Edeson. Script by John Huston and Howard Koch! Given the provenance of this one it’s rather mysterious why this movie has been so overlooked. Perhaps it’s simply its oddness.

Fitzgerald gives a classic cinematic portrait of pure evil as a spurned spouse who makes a pact with two strangers, Lorre, the small-time drunken thief, and Greenstreet, the corrupt solicitor. According to legend, if three strangers gather before the fabled idol of Kwan Yin and make a common wish on New Year’s Eve, the wish must be granted. Everybody has a plan – including Kwan Yin. Sometimes the worse thing that can happen is that the universe gives us exactly what we want.

You’ll have to look for this one. There is a NTSC print-on-demand DVD. Well worth it.

Robin, Stephen: Thanks, more films added to the future viewing list!

Negulesco also directed Lorre and Greenstreet in The Mask of Dimitrios. It’s a minor work but one I enjoyed. Also another noir set outside the USA.

In Australia, the ABC used to show RKO films in the early hours of the morning, many of which were either noir (e.g. Armored Car Robery and The Set-up (1949)), or noir-adjacent (e.g. The Cat People (1942) and The Seventh Victim (1943)). It was a great education in mid-century American cinema.

The Phenix City Story (1955) is an overlooked gem.

Point Blank (1967) is based on the Parker series written by Donald E. Westlake (as Richard Stark). The best book of the series is Butcher’s Moon, which remains one of my favourite crime novels.

Note: Donald E. Westlake wrote the script for The Grifters, based on the Jim Thompson novel. The novel and the film are both excellent.

Here are a few less-well-known noir novels I recommend:

Black Wings Has My Angel – Elliott Chaze

The Fire Trap – Owen Cameron

.44 – H. A. DeRosso (a noir western that’s more nihilistic than any crime book I’ve read)

All three novels are available at the Internet Archive.

Thanks, Andrew. I’ve definitely seen The Phenix City Story but remember little about it. The Outfit on the list above is another Westlake/Stark story that’s pretty similar to Point Blank but without the non-linear editing, and with two guys causing trouble for a crime syndicate instead of one. Also a cast of older noir actors: Robert Ryan (in one of his last roles), Jane Greer, Jim Carey and Elisha Cook.

And thanks for the reminder about The Grifters. I’ve actually got that one on blu-ray but it hadn’t occurred to me to watch it again while going through all these films.

Hollywood seems inexorably drawn to the character: Lee Marvin (Point Blank), Jim Brown (The Split), Robert Duvall (The Outfit), Peter Coyote (Slayground), Mel Gibson (Payback), Jason Statham (Parker), Mark Wahlberg (Play Dirty).

As I started reading the series years after seeing Point Blank, I always picture Parker as Lee Marvin. I’m reluctant to risk replacing him by watching any of the other films.

PS The absence of Pepe Le Moko (1937) and Les Diaboliques (1955) suggests that foreign noirs weren’t considered by the editors. Film noir without any French films? Sacre bleu!

You’d think by now someone would have attempted a Parker TV series. Maybe they have and I’ve never heard of it? I get that all the time with film actors invading your head when you’re reading a book. Sometimes it’s fine, other times it’s annoying.

I think S&W were determined to stick to US films although they did include Night and the City which is almost wholly British. If they had included non-US films the book might easily be twice the size: UK, France, Germany and Japan would occupy a lot of space just for a start. I watched Rififi again because I’d been enjoying Dassin’s films but it’s not in the book.