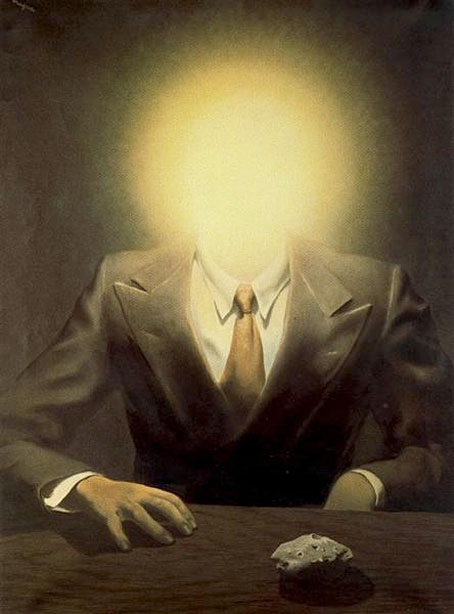

The Pleasure Principle (Portrait of Edward James) (1937) by René Magritte.

I was reading a book about Surrealism recently that I won’t shame by naming even though it was a bad piece of work: rambling, repetitive and with one section padded out by unfounded speculation. I managed to get a third of the way through before losing my patience when the author began to refer repeatedly to the wealthy British art patron “Edward Jones”. Edward James, as he’s more usually known, is a name guaranteed to turn up eventually in histories of 20th-century Surrealist art; despite not considering himself a collector James managed to amass the largest personal accumulation of Surrealist art in the world. For several years he was a patron of many artists including Dalí, Magritte and Leonora Carrington, becoming a life-long friend of the latter when they both moved to Mexico. He was also the model for some of Magritte’s paintings, including the very influential Reproduction Forbidden. The book that misnamed him was from a major British publisher, one who I usually regard as reliable which makes an error such as this especially annoying.

Anyway…much of the history of Edward James’s involvement with the Surrealists is recounted in this hour-long documentary made in 1995 by Avery Danziger and Sarah Stein, a run through James’s charmed life, from gilded youth as an aristocrat and inheritor of vast wealth, to his old age as “Uncle Edward”, a benevolent eccentric living in the Mexican jungle at Xilitla where he spent many years constructing his own work of art, the concrete fantasia known as Las Pozas. Substantial portions of the documentary are lifted from Patrick Boyle’s The Secret Life of Edward James, a TV profile made in 1978 that caught the man at a time when Surrealism in Britain was briefly trendy again thanks to a large retrospective exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London. Danziger and Stein’s film is a kind of supplement to Boyle’s, showing us a more complete Las Pozas while fleshing out the impressions of James via new interviews with his friends and colleagues. Not everyone who gets thanked at the end made the final cut, so there’s no Leonor Fini unfortunately, but Leonora Carrington is present via shots from the Boyle film and extracts from a taped interview.

One aspect of Las Pozas that seldom gets mentioned (although I think George Melly might have made the connection) is the degree to which the place fits into the tradition of folly-building by wealthy British aristocrats. Follies are a familiar architectural feature of Britain’s stately homes, and being architectural caprices they come in all shapes and sizes. Most tend to be small one-off constructions, often taking the form of towers or fake ruins. The only folly comparable in scale to Las Pozas is Portmeirion, the pastiche Mediterranean town built by Clough Williams-Ellis on the coast of north Wales. Williams-Ellis, like James, spent decades tinkering with his pet project, and both locations have ended up supporting themselves by offering hotel facilities to tourists. Portmeirion, however, lacks the strangeness of the cement anomalies at Las Pozas; the only thing that’s strange about the place is its departure from vernacular Welsh architecture. Imitation and trompe-l’oeil are common elements among British follies. The closest that Portmeirion came to Surrealism was in the 1960s when it was used as a location for The Prisoner TV series. I imagine James would have found Williams-Ellis’s architectural taste rather too neat and refined. Las Pozas is a wild place that must require continual attention to prevent it from being consumed by the surrounding jungle. One of the houses there is named after Max Ernst (Danziger and Stein interview the owner), and it’s the fantasy jungles in the paintings of Ernst and Henri Rousseau that Las Pozas takes as its model.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Eco del Universo

• The Secret Life of Edward James

• Palais Idéal panoramas

• Las Pozas panoramas

• Return to Las Pozas

• Las Pozas and Edward James

“The book that misnamed him was from a major British publisher, one who I usually regard as reliable…”

Shouldn’t be surprising in a time when knowledge is kept for an elite while the (pardon the expressions) aren’t meant to be educated.

So in this case, expending monies that could go to increased profits is withheld from hiring actually qualified fact checkers.

Catching errors isn’t worth the even tiny increased expense.

Ever since Thatcher and Reagan, things usually change for the worse.

Sorry for the cynicism, but that’s what happens when sees the same behavior too many times. (Tangential illustration: that panel popping off a 737 while climbing from takeoff. I’m it was worth the pennies saved by Boeing and its supplier.)

Most publishers hire proof-checkers–or have them on their staff–but they mainly check spelling and other typographic errors. I think books only get checked for facts if they’re going to receive a lot of press attention, or when the authors do it themselves; you often see friends and colleagues being thanked in the acknowledgements for reading an MS. In the case of the book I was reading, I wouldn’t expect a publisher to know who Edward James was but the writer certainly should, especially when he’s the subject of two very famous Magritte paintings, one of which even names him.

On the subject of follies, I’m reminded of a comment by J G Ballard in his autobiography;

….the vast Hardoon estate in the centre of the International Settlement, created by an Iraqi property tycoon who was told by a fortune teller that if he ever stopped building he would die, and who then went on constructing elaborate pavillions all over Shanghai, many of them structures with no doors or windows (Miracles of Life p9)

Silas Aaron Hardoon was indeed from Iraq, but I have never found any mention of these buidings in any account of his life, which further increases the mystery of this bizarre story of follies – if you will -not as a celebration of life but in a way similar to the more haunting architecture of the surrealists, De Chirico in particular.

One of the unfortunate features of British follies is that most of them are in parks or remote gardens or other non-urban areas. I’d love to see more of them in towns or cities. Fleetwood, the town where I was born, is notable for having a lighthouse standing in the middle of one of its streets, something I always found delightfully bizarre. I have a guide to British follies that includes the fake houses in Leinster Gardens, London, which hide a portion of the Underground system:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leinster_Gardens

Hardoon’s example sounds a little like the woman who never stopped building the Winchester Mystery House in the hope that all the ghosts of people killed by Winchester rifles would lose themselves in the useless rooms and stairways. Hardoon turned up later as a character in The Wind from Nowhere, the first of Ballard’s megalomaniac villians, and fittingly a mad architect.