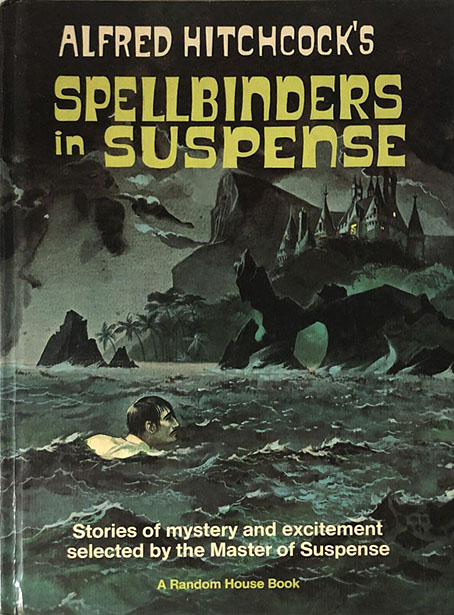

Cover art by Harold Isen, 1967.

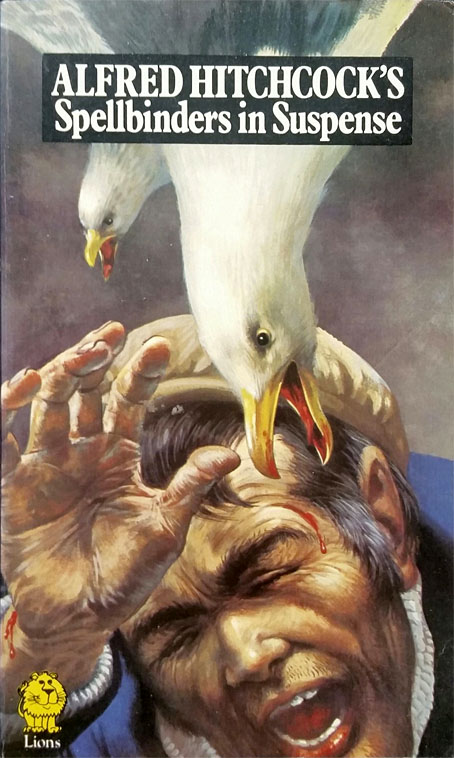

I watched Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds again recently, after which I went looking for the contents list of the collection where I first read Daphne du Maurier’s story. The book in question, Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbinders in Suspense, is one of the many anthologies that used the director’s name to lure potential purchasers, even though Hitchcock didn’t choose any of the stories and didn’t write any of the introductory notes or mini essays that these volumes usually contain. Spellbinders in Suspense was first published in 1967, and is one of the few such collections to feature a story that relates to one of Hitchcock’s films, so it’s odd that Random House chose to depict a scene from Richard Connell’s The Most Dangerous Game on the cover. The copy that I owned was a Fontana Lions paperback from 1974 which rectified this with a cover that certainly stimulated my interest; growing up in a seaside town I didn’t need much convincing about the viciousness of the common seagull. The book has two further Hitchcock connections via Roald Dahl’s The Man from the South, which had been dramatised in 1960 for the Alfred Hitchcock Presents TV series, and Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper, a story by Psycho author Robert Bloch that first appeared in Weird Tales and which turns up in many anthologies.

Cover artist unknown, 1974.

I don’t know when I first saw The Birds but it must have preceded my reading of the book since I remember being surprised at how different du Maurier’s story was to the film. Hitchcock and screenwriter Evan Hunter kept the basic idea of inexplicable bird attacks but moved the location from Cornwall to northern California, retaining a single incident in the scene where a dead seagull is found on a doorstep. The page for Spellbinders in Suspense at the Hitchcock Zone—an excellent information resource—has some of the illustrations by Harold Isen that appeared in the hardback edition, including a drawing of yet more marauding seagulls.

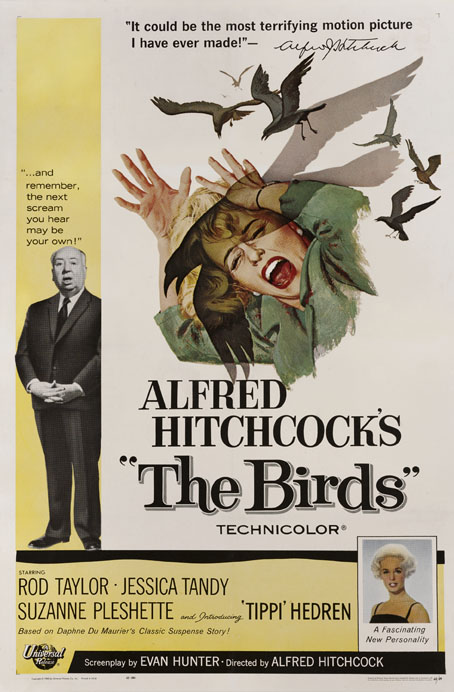

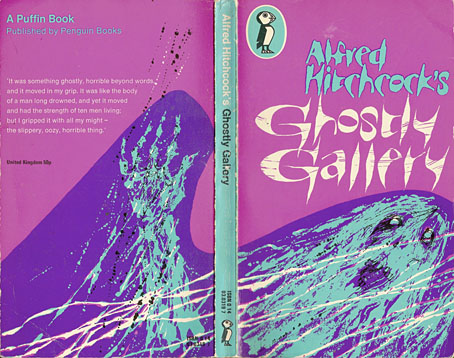

If you want an idea of Hitchcock’s personal popularity and the power of the Hitchcock brand, look no further than the US poster for The Birds in which the director’s name is almost as large as the title (and much more prominent than those of the actors), while the man himself is also there to offer further enticement. Hitchcock was the first film director I became aware of by name, although when I was 10 or 11 I doubt I could have told you what it was that a film director actually did. The ubiquity of the Hitchcock brand made his presence unavoidable in the 1950s, 60s and 70s in a manner more usually reserved for film stars and pop stars; in addition to books, radio shows and the TV series there was Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, which launched in 1956 and was still running 50 years later; also a long-playing record, Music To Be Murdered By, in which the director’s familiar drawl delivers snatches of black humour between each musical selection. In the book department, the Hitchcock Zone lists 127 Hitchcock-themed anthologies, many of which (like Spellbinders in Suspense) received multiple reprints. And those 127 volumes are just the collections. There’s also Robert Arthur’s mystery novels for younger readers, Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators (1964–87), a 43-volume series in which a trio of Californian boys undertake investigations—many of them with a spooky flavour—whose outcome they report to Mr Hitchcock at the end of each story. I read the first few books in the series, also another story collection compiled by Robert Arthur, Alfred Hitchcock’s Ghostly Gallery (1962), a book which in its Puffin reprint gave me my first encounter with The Upper Berth, F. Marion Crawford’s frequently anthologised tale of clammy nautical horror. Ghostly Gallery was another illustrated collection, with scratchy drawings by Barry Wilkinson.

Cover art by Barry Wilkinson. The Puffin edition dates from 1967 but this edition has a decimal price which places it circa 1971.

The extension of the Hitchcock brand into books aimed at children is a curious thing when none of his films are intended for a young audience. My edition of Spellbinders in Suspense was published by a juvenile imprint yet all the stories are ostensibly adult fare. Children in Hitchcock’s cinema are either treated as a nuisance (the small boy who has his balloon burst by Bruno in Strangers on a Train) or end up in serious peril, as they do in The Birds, The Man Who Knew Too Much (kidnapped and threatened with murder), Strangers on a Train (an out-of-control merry-go-around), and, notoriously, in Sabotage, where another small boy is made to unwittingly carry a time-bomb that blows him and a busload of passengers to pieces. Strangers on a Train also reinforces the Hitchcock brand by showing Farley Granger’s character with one of the earliest anthologies, Alfred Hitchcock’s Fireside Book of Suspense Stories, in the scenes on the train at the beginning of the film.

Product placement: Robert Walker and Farley Granger in Strangers on a Train (1951).

All of this retrospection has had me wondering whether Hitchcock might have been interested in adapting another Daphne du Maurier story, Don’t Look Now, since The Birds was his second adaptation after Rebecca. Supernatural stories turn up in the Hitchcock TV series, and there are several more anthologies like Ghostly Gallery yet the films mostly avoid the paranormal (although Vertigo toys with the idea for its first half hour or so). Nevertheless, the subject is given ambivalent treatment in du Maurier’s story which has other qualities that might have appealed. The story wasn’t published until late 1970, however, by which time Hitchcock was planning his return to London with Frenzy. And besides which, the film we have is more than adequate, as well as being a much more faithful adaptation than Melanie Daniels’ journey into avian nightmare.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Painted devils

• The poster art of Josef Vyletal

• The Magic Shop by HG Wells

Great roundup here. I had no idea there were that many Hitchcock spinoff books, though I knew there were a good number. In spite of the possible quality of the contents, I am forced to say that the cover for “Ghostly Gallery” just may be the least attractive book cover I’ve ever seen. In a related observation (and you will know exactly what I’m talking about), I wonder if there is a name for that scratchy, sketchy illustration style that was so popular from the late-50s to about the mid-60s (roughly). I think of it as “existential style”, as it seems to show up on everything from gritty novels to philosophy texts in that era.

A well-worn “Spellbinders in Suspense” hardcover was a gift from an aunt, and I all the “Three Investigators” books my local library had during one summer in the early 70s.

Eric: I read all the ones in the local library as well. I forget how many, and don’t even remember the particular books aside from The Mystery of the Talking Skull.

Jim: I quite like that cover! But then I’ve just finished work on an illustration that also uses a lot of magenta so I may be biased. The designers at Puffin weren’t immune from the prevailing trends in quasi-psychedelic lurid colour schemes.

As to the scratchy art style, I know what you mean, this happens a lot with illustrators, many of whom seem to emerge at around the same time with a similar art style. I think some of it can be put down to the influence of a single stylist, as in the case of Ronald Searle whose wiry lines were very influential for a while. In other cases I think it may be more to do with the way the publishing world encourages trends. One publisher has a success with a particular look then a rival publisher decides to follow suit. If they can’t get the artist responsible then they encourage someone else to imitate the style. This happened with Chris Foss in the 1970s, his brand of airbrushed spaceship art was so popular that other illustrators became imitators. I can’t say if this is the case with Barry Wilkinson, however, that may well be a style he evolved independently.

One of the leading artists of the scratchy/splattery style is Charles Keeping ( https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2015/09/22/charles-keepings-beowulf/ ), a very prolific illustrator. Leonard Baskin may have originated the style but that’s just a guess.

For some reason that continues to elude me I have never been sympathetic to Alfred Hitchcock’s work. I see what others see but some connection never gets made. I admire Notorious but only because of Ben Hecht’s script and the performance of Claude Rains. I still find it rather mysterious when Vertigo is named as one of the greatest films ever made. (While I’m confessing my sins I should point out I have the same issue with the work of Christopher Nolan.)

I don’t get it.

ps: I was attacked by a bird once. Near as I can figure the bird was nesting and I got too close. It didn’t try to peck out my eyes but bumped me until I hastened away. At a certain distance it ignored me. Not exactly an apocalypse. I think when the animal revolt actually begins it’ll more of a Phase IV kind of thing anyway.

If you ask Martin Scorsese he’ll tell you that Hitchcock represents “the height of technique”. That’s an Appeal to Authority but I think Marty’s opinion here counts for more than mine even though I’d say the same. You can see how much he cared about his technique in the Hitchcock/Truffaut book.

I think the problem he had, and still has to some degree, is that the success of his self-branding tended to make people overlook the artistic success of his films. I went through a period when I stopped paying much attention to them because they seemed so familiar. When I watch them now I realise I’d only been watching for the set-piece moments and missing a lot of the artistry elsewhere. I’ve been reminded of this recently when watching masses of film noir from the 1940s and 50s. Since Hitchcock made a few films that are included in this genre (Notorious among them) I’ve been watching these again. There are many excellent films from this period but many middling or mediocre ones as well. Hitchcock’s film noir entries immediately strike you as being of the highest quality, they seem assured and confident in a way that many of the lesser films of this period don’t at all. Incidentally, I think Ingrid Bergman is great in Notorious as well.

I think people also miss the degree to which Hitchcock continued to experiment with the medium; this was one area where his success did work in his favour since it gave him maximum control over his productions. There’s no other director of his generation that you can point to who was globally successful yet experimented so much with the medium while still crafting soldily commercial stories: Lifeboat restricting the set to the smallest possible space; Rear Window telling the story from the viewpoint of a wheelchair-bound character; Rope telling the story in a single set and with the minimum of edits. Then there’s The Birds which I think is the first non-SF feature film that has no music yet an all-electronic soundtrack.

As for Vertigo, I’ve always thought it wildly over-rated despite praise from Chris Marker et al. I like the atmosphere and Bernard Herrmann’s music but the story is preposterous and gets ludicrous towards the end. Hitchcock originally wanted to adapt Boileau-Narcejac’s Les Diaboliques but missed out on the rights so ended up adapting another of their stories as compensation. He would have been better doing something entirely different.

My younger brother read maybe a dozen of the Three Investigators books, more than a half-century ago; he would probably be stunned to know how many there ultimately were. I was given the Hitchcock/Arthur compilations ALFRED HITCHCOCK’S HAUNTED HOUSEFUL and AH’S GHOSTLY GALLERY in the early ’60s; the former was for younger readers, the latter more for a YA audience. In hardcover, they had eerie color covers and monochrome interior illustrations by the great and underappreciated Fred Banbery. I still have copies, and those artworks still evoke a lovely frisson of spookiness. Banbery also did wonderful covers for some of the adult Hitchcock compilations–e.g., STORIES FOR LATE AT NIGHT–that were used for both hardcovers and paperbacks.

Hi Michael. Thanks for the illustrator info. I’d seen the cover of Haunted Houseful before but didn’t know that one was illustrated as well.