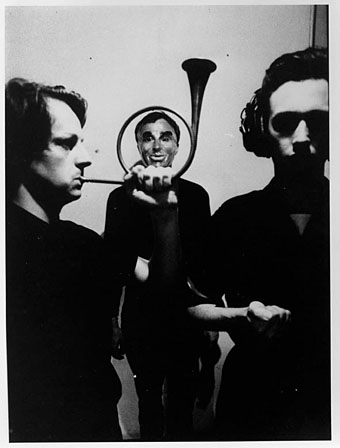

Cabaret Voltaire, circa 1981. Left to right: Richard H. Kirk, Chris Watson, Stephen Mallinder.

…A few brief facts. CV came about from a mutual interest in producing “sound” rather than “music”, a few years ago, making very rare live appearances from time to time. Now an interest has developed in the band, we are playing live more frequently instead of just recording. CV dislike the sick commercialism which pervades most “contemporary music”.

At the moment we are working on a basis which involves two types of performance. A “set” which consists of songs, and a set which is completely improvised, lasting from 20 minutes to “x” number of hours. CV also use films + slides as lighting in live performance. A CV concert is like a bad acid trip; CV want to create total sensory derangement. MIT UND OHNE POLITIK, UNVERNUNFTIGKEIT.

INFLUENCES — “anything which is unacceptable”.

The band’s line up is —

RICHARD – Guitar, Clarinet, Tapes, Vocals.

MAL – Bass, Electronic Percussion, Lead Vocals.

CHRIS – Electronics, Tape, Vocals.Early band correspondence with a German fanzine

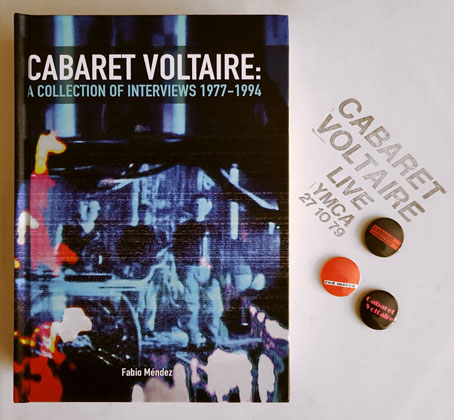

Another week, another book of music talk. Cabaret Voltaire: A Collection of Interviews 1977–1994 was published two years ago but I only just discovered it as a result of my recent cycling through the Cabs’ discography. I’ve never been a great reader of music books yet here I am with three of them devoted to this particular group. Fabio Méndez’s collection joins Cabaret Voltaire: The Art of the Sixth Sense, the first Cabs book from 1984, in which Mick Fish and D. Hallberry interrogate Kirk and Mallinder about their progress to date; and Industrial Evolution, a reprint of the Sixth Sense interviews plus newer ones appended to Fish’s memoir about life in the Cabs’ home town of Sheffield during the 1980s. The Méndez collection is the most substantial of the three, gathering articles from fanzines, magazines and newspapers, and translating into English many pieces from European publications.

Badges not included.

As with Coil, I’ve always liked hearing what Kirk, Mallinder and Watson had to say. There was a fair amount of historical intersection between the two groups, Cabaret Voltaire having been a part of the first wave of Industrial music along with Throbbing Gristle, 23 Skidoo (whose records were produced by TG & CV), Clock DVA and the rest; later on the Cabs were part of the Some Bizzare stable along with Soft Cell, Coil, Einstürzende Neubauten and others. One of the interviews in Méndez’s book is from Stabmental, a short-lived fanzine edited in the early 1980s by a pre-Coil Geoff Rushton/John Balance. The zine ended its run with a cassette compilation, The Men With The Deadly Dreams, which included two exclusive recordings by Chris Watson and Richard Kirk. Watson’s piece, which applies cut-up theory to a radio news broadcast, is a good example of Cabaret Voltaire’s engagements with William Burroughs’ speculations about electronic media. Further examples of cut-up theory may be found in the group’s lyrics and in the video material they created, initially for use as projections while playing live, then later for their music videos which were in the vanguard of the form in the early 1980s.

A lot of the things we do tend to get glossed over. We’ll talk to anyone. We do loads of interviews with fanzines.

Unidentified group member, 1980

582 pages of interviews with a group that never had any kind of popular success is more information than most people would ever want or need. But as with Nick Soulsby’s Coil book, Méndez is doing future historians a service by resurrecting material from scarce and ephemeral sources. The post-punk period from 1978 to 1982 was a uniquely fertile musical moment, especially in Britain. For a few years absolutely anything seemed possible, with much of the wilder activity being logged and discussed in fanzines like Stabmental which usually had a limited circulation (often distributed by mail order) and a print run of a few hundred copies at most. The British music press also covered this scene, of course, but only up to a point, especially when the music was pushing the boundaries of the possible or the commercially acceptable. Méndez’s book emphasises the differences between the music-press approach—where the article is often as much about the writer as the group itself—and the fanzine interview which tends to be a list of questions with a small amount of contextual commentary. Fanzines were a circumscribed medium but they had advantages over the music papers; sincerity, for a start, allied with genuine enthusiasm and fewer of the tics that made reading the music press each week such a chore. The small publications weren’t always free of the bad habits of the weeklies but there was less of the journalistic posturing, the ignorant dismissal of whole areas of music, and the relentless snark and sarcasm which you’ll find thriving today on social media. The drawbacks of the fanzines were mostly about quality; fact-checking was often non-existent. Méndez’s book is littered with footnotes that log the errors present in the transcripts.

Which bands are influential on your music?

Chris: “Can, Neu!, Kraftwerk, Captain Beefheart…especially Can have influenced us.”Spex magazine interview, 1980

Questions about influence are a common feature of any interview with creative people. Chris Watson’s reply is the first example I’ve seen of the Cabs mentioning so many German groups, as well as Captain Beefheart. A recurrent theme of these interviews concerns the group’s unusual trajectory, a career which evolved through a series of changes in direction that weren’t always predictable. The trio had started out in 1974 as resolute non-musicians and sound-collage provocateurs with Dadaist intentions; the music-making took time to develop. By the late 1970s the group that now called itself Cabaret Voltaire had become a more disturbed and disturbing counterpart to Sheffield’s other electronic music ensemble, The Human League. When Chris Watson departed in 1981 Kirk and Mallinder joined the Some Bizzare roster and followed the League to Virgin Records where a substantial advance helped the pair upgrade their equipment, launch their own independent music and video label, Doublevision, and record some of their best work.

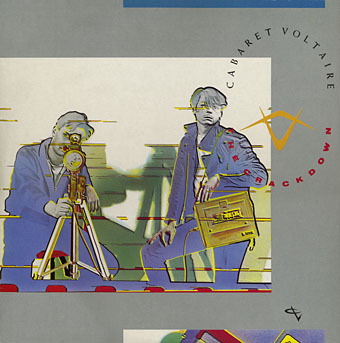

The Crackdown (1983).

For groups with an ever-growing audience, the post-punk era saw a continual fretting over the issue of selling out, the question being whether it was possible to move from the independent world to a bigger label while retaining all the spiky and unpredictable originality that set independent musicians apart from their more commercial contemporaries. Neville Brody’s sleeve art for The Last Testament (1982), a Fetish Records compilation, foregrounds these anxieties, with the hand of big business grasping for the independent fish. Cabaret Voltaire worried over this themselves but their deal with Virgin was brokered by Some Bizzare and pitched in their favour. All the talk from this period is of a perpetually subversive operation, infiltrating the mainstream with aggressive rhythms freighted with the underground concerns of Industrial music. Their first album on Virgin was named after that policy beloved of authoritarians everywhere, The Crackdown, with music that included a rhythm borrowed from a Haitian voodoo ceremony, dialogue sampled from a TV documentary about torture in the British army, and a track bearing the title Why Kill Time (When You Can Kill Yourself). This last is an example of the Cabs’ sly sense of humour, a phrase uttered by Nanette Newman’s Existentialist character in Tony Hancock’s The Rebel (always listed as a favourite CV film), but separated from its source it’s not the kind of sentiment you’d expect to find in the pop charts.

The group’s next move was the one that disappointed me when they signed to Parlophone in the mid-1980s where the A&R people evidently wanted a more commercial, chart-oriented act. Kirk and Mallinder didn’t seem troubled by the dilution of their sound but I felt something substantial had been lost at a time when younger groups—Depeche Mode, the second-wave Industrial outfits—were borrowing liberally from the Virgin recordings. At Virgin the Cabs’ attitude had been summarised by a slogan printed one of the singles: “Conform to Deform”. The phrase was the work of Some Bizzare boss Stevo, and a statement that Kirk and Mallinder said they disagreed with—they didn’t want to conform to the expectations of a record label—but it was still an oppositional stance. Some of the non-conformism was carried over to the first Parlophone album, Code (1987), but the follow-up, the house-influenced Groovy, Laidback And Nasty (1990), is an album I’ve never liked, a release blighted by a bad title, bad cover art and attempts at proper singing in place of the growls and menacing whispers of the earlier albums. Stephen Mallinder has many talents but singing like other artists isn’t one of them. I’m curious to see how they justify this period in the later interviews; my feeling at the time was that there was too much conforming and not enough deforming. Flicking through the end of Méndez’s book I spotted a dismissal of complaints like these by Richard Kirk, with the suggestion that those complaining didn’t really get the changes in direction. My problem with the Parlophone albums, and with some of the subsequent recordings, was that the direction they were now following was all too easy to get, and evidence of a group who weren’t succeeding on their own terms. When Coil released their own response to rave culture, Love’s Secret Domain, the contrast with Groovy, Laidback And Nasty was stark. Cabaret Voltaire’s music had lost all its distinguishing features while the Coil album couldn’t have been made by anyone else.

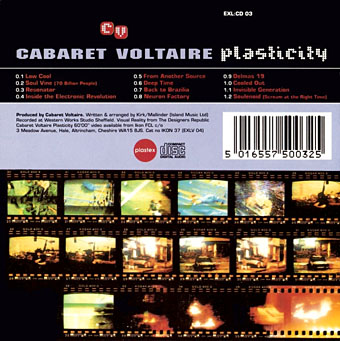

Plasticity (1992).

It’s a perennial problem, how to develop your art without losing your audience; and how to be part of an audience without insisting that your favourite artists never change or evolve. In the case of the Cabs the later changes of direction weren’t all negative. I like the Plasticity album where familiar themes—William Burroughs, voodoo, the CV obsession with The Outer Limits—were combined with contemporary electronic rhythms. And the packaging from this period was looking good again thanks to the Designers Republic. But Stephen Mallinder was lost in the shadows by this time, leaving all the later releases sounding like yet more Kirk solo projects.

It’s pointless to speculate about the alternative paths that Cabaret Voltaire might have taken but I do it anyway. I wonder how they could have developed in the late 1980s if they’d signed to Mute instead of Parlophone, and created a dub apocalypse with Adrian Sherwood to rival Mark Stewart’s terminally-paranoid, Burroughs-inflected masterpiece As The Veneer Of Democracy Starts To Fade. (Sherwood did produce most of the Cabs’ Code album but you wouldn’t know it.) Or a collaboration with Bill Laswell and friends, something that Mallinder said he had in mind in 1986. Both Laswell and the Cabs had various degrees of involvement with William Burroughs, especially Laswell who recorded his Burroughs-themed Seven Souls album in 1989. I reel when considering these possibilities (if only…if only…) but it’s all just history now, frozen on disc and in the pages of this book.

Cabaret Voltaire: A Collection of Interviews 1977–1994 is available via mail order.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Richard H. Kirk, 1956–2021

• Recoil and Cabaret Voltaire

• Pow-Wow by Stephen Mallinder

• TV Wipeout revisited

• Doublevision Presents Cabaret Voltaire

• Just the ticket: Cabaret Voltaire

• European Rendezvous by CTI

• TV Wipeout

• Seven Songs by 23 Skidoo

• Elemental 7 by CTI

• The Crackdown by Cabaret Voltaire

• Neville Brody and Fetish Records

I liked _Code_, and still do, but I clearly remember buying _Groovy, Laidback, and Nasty_, being utterly appalled, and returning it to the store. Happily, they got better again after that.

I’ve still got my Groovy… CD but it doesn’t get played very often. I tried listening to it again while writing this piece but couldn’t get through it all.