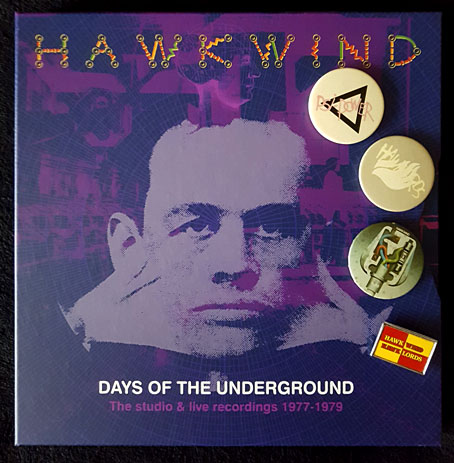

Antique badges not included.

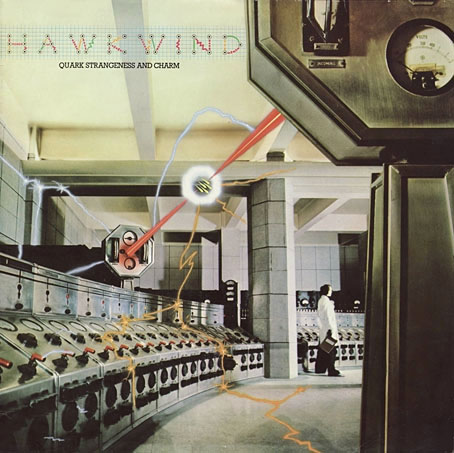

My weekend has been spent immersed in Days Of The Underground, the latest box of Hawkwind albums from Cherry Red Records. I’d avoided many of the earlier sets but this one was irresistible for being a 10-disc collection (8 CDs and 2 blu-rays), the core of which is three of the four albums recorded by the group for the Charisma label–Quark, Strangeness And Charm (1977), 25 Years On (credited to Hawklords, 1978), and PXR 5 (1979)–with all three albums being given the Steven Wilson remix treatment. The studio material is complemented by further Wilson mixes of live recordings and alternate takes, plus demo tracks (previously available but I didn’t have them). You also get three bonus video clips: Hawkwind (minus Dave Brock) playing the Quark single on Marc Bolan’s TV show in 1977, together with two promo films from the 1978 Hawklords concert at Brunel University. Absent from the set is the group’s first album for Charisma, Astounding Sounds, Amazing Music (1976), also the two singles that were released that year. I’ve not seen any explanation for these omissions but reasons may include the uneven quality of the music (recorded shortly before the group imploded), and Dave Brock’s lasting dislike of the album.

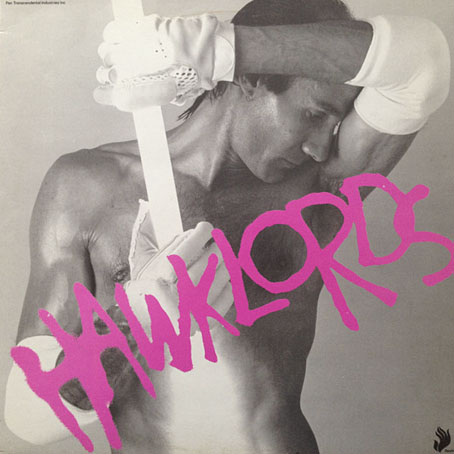

Cover design by Hipgnosis; photography by Peter Christopherson with graphics by Geoff Halpin. Aubrey Powell says that Robert Calvert commissioned this one after the pair met each other at a party. The photography made use of the interior of Battersea Power Station in the same year that Hipgnosis used the building for a rather more famous album cover.

Steven Wilson did a great job of remixing the Warrior On The Edge Of Time album so I had high hopes for this set, hopes that have been substantially fulfilled. Many of the adjustments are individually minor–boosted bass, more prominent keyboards, some extended intros–but taken together they offer a refreshed experience of three very familiar albums. The packaging has been well-designed by the estimable Phil Smee with a booklet that presents a snapshot of the graphics produced for the group during this period, not only album artwork but also posters, ads and pages from the tour programmes. As a bonus there’s a small reproduction of the 1977 tour poster, a welcome inclusion since I used to own an original one of these which I’ve either misplaced or lost altogether. The attention to detail extends to the animated graphics of the blu-ray interface; when the Quark album is playing you can watch sparks dancing around the control room. The Marc Bolan TV appearance was something I’d seen many times before (including its original broadcast) but the live Hawklords films are revelatory when there’s so little footage of the band from the 1970s with synched sound. The performances of PSI Power and 25 Years offer a frustratingly brief taste of Robert Calvert’s magnetic stage presence, and make me hope that a video of the entire concert may be released eventually.

Cover art by Philip Tonkyn.

Robert Calvert is the key figure here, to a degree that Hawkwind’s Charisma years are also known as the Calvert years, this being the period when the group’s part-time lyricist, occasional singer and conceptual contributor graduated to lead vocalist and songwriter. Calvert’s new role as front man changed Hawkwind from an ensemble of underground freaks into a more typical rock group, albeit one with a very theatrical singer prone to changing outfits to suit the songs, and with props that included a loudhailer, a machine-gun (fake) and a sabre (real). The songs became shorter and, in places, poppier, although none of the singles managed to repeat the chart success of the Calvert-penned Silver Machine. Nevertheless, Brock and Calvert were a great song-writing team, and the lyrics that Calvert wrote from 1976 to 1978 are better than anything else in the discography: witty, alliterative, and filled with clever rhymes that range widely in their subject matter, from the usual science-fiction fare to Calvert’s own obsessions, especially aircraft and flying. Calvert’s approach to science fiction was more sophisticated than the freaks-in-space approach of the group’s UA years. You get a sense of this from his contributions to the Space Ritual album (only Calvert would have known what an orgone accumulator was), but his Charisma songs go much further, condensing whole novels—Roger Zelazny’s Damnation Alley and Jack of Shadows, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451—while maintaining the spirit of the New Wave of SF, where the emphasis was as much on inner as outer space.

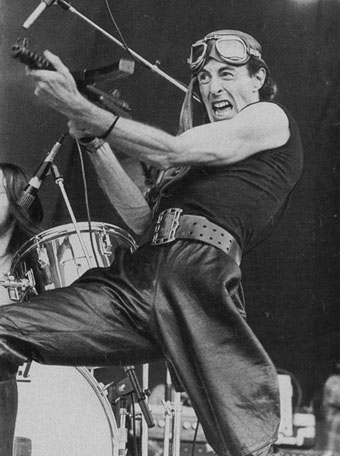

Robert Calvert in full flight at Cardiff Castle, 1976.

This latter aspect of Calvert’s time with Hawkwind remains underexamined, although Joe Banks explored many of the literary connections in his excellent study of the group’s first decade. Calvert had been contributing to Friends/Frendz magazine in the early 1970s when the staff there were sharing offices with Michael Moorcock’s pioneering SF magazine New Worlds. Two Calvert poems subsequently turned up in New Worlds Quarterly, while more were published in The Purple Hours (1974), a poetry zine edited by Lisa Conesa which included contributions from Brian Aldiss and John Brunner, as well as the original Moorcock text for Hawkwind’s Sonic Attack, a piece which Calvert had given its definitive reading the year before on Space Ritual. Two of Calvert’s Purple Hours poems, The Starfarer’s Despatch and The Clone’s Poem, were later combined to create the lyrics to the first number on the Quark album, Spirit Of The Age, a song that quickly became a staple of the group’s live repertoire.

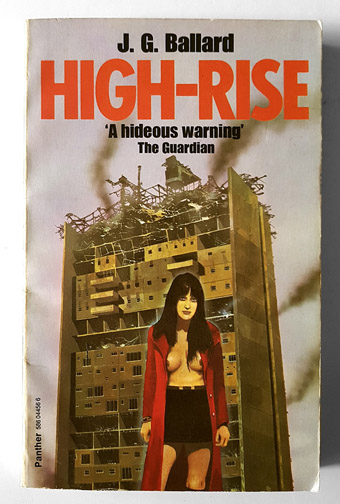

Panther paperback, 1977, with unusually poor art by Chris Foss.

Those are the documented facts. More arguable are the connections to JG Ballard, an author who shared Calvert’s aviation obsessions. I’ve always regarded the influence here as very obvious but this may be a result of my over-familiarity with both Hawkwind’s music and Ballard’s fiction. For the record, I offer as evidence: the line from 10 Seconds Of Forever on Space Ritual that mentions “the vermilion deserts of Mars, the jewelled forests of Venus”, something I always take as oblique references (via Ray Bradbury) to Vermilion Sands and The Crystal World. Then there’s High Rise, a song which shares a title with Ballard’s novel although it’s not necessarily based on it. (Joe Banks notes that Calvert had lived in a typical example of high-rise Brutalism in Margate.) Ballard’s hyphenated High-Rise was published in 1975, with a paperback arriving in 1977, the same year the song appeared in Hawkwind’s set lists. Moorcock says there was no connection to the novel, while Ballard refused to believe that a bunch of freaks from Notting Hill Gate had been inspired by his books, and yet…when Calvert is detailing all the problems of skyscraper living he mentions “high-speed lifts and elevators”, a feature you won’t find in any of Britain’s decayed social housing but which is mentioned throughout the novel. He also refers to someone jumping from the 99th floor, a detail that brings to mind not only one of the deaths in the novel but also The Man on the 99th Floor, a Ballard story from 1962 that involves suicide by skyscraper. Calvert’s High Rise eventually appeared on the PXR 5 album, together with another song with Ballardian overtones, the punk-influenced thrash of Death Trap. This is a Calvert lyric that’s as much Ballard’s Crash set to music as the better-known Warm Leatherette by The Normal, and a song that was played in tandem with High Rise on the 1978 tour.

Design by Barney Bubbles. Photo by Chris Gabrin.

The lethal fetishism of Crash brings us to the strangest Hawkwind scenario of all, 25 Years On, the album where Hawkwind became Hawklords for a year. The album and the tour which promoted it were intended to showcase a dystopian science-fiction project created by Calvert and designer Barney Bubbles concerning the activities of Pan Transcendental Industries (slogan: “Reality you can rely on”), a corporation whose city-sized “Metaphactories” are in the business of the industrialisation of religion. The concept was detailed in a small booklet that accompanied early pressings of the album (also used as the tour programme), a fascinating if not very enlightening document which blends photography by Brian Griffin and Chris Gabrin with Zener Card graphics (a reference to the song PSI Power) and several pages of evocative text. Some of this reads like outtakes from Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition, especially the following:

Assembly Rooms

Staffed by car crash victims whose function is to generate new forms of social behaviour through the transformation of private into public fantasies. The institute is equipped to stimulate fantasies that once rehearsed cause a chain reaction by suggesting further elaborations.Computers

In a soft environment of hypnotic suggestions, various athletic facilities are provided to aid physical voluntary self experimentation. Here Nature, obliterated by the new psycho-technology, returns from its total eclipse as an unstable series of superimposed and simultaneous activities into egalitarian flight, scar tissue and immolation.

You can read the whole booklet here. Barney Bubbles complemented the text with designs that were closer to his innovative New Wave covers for Stiff and Radar Records than his earlier psychedelic art. 25 Years On stands apart from the Hawkwind discography with its homoerotic cover photo, the band name sprayed in the vivid pink common to punk graphics, and the de Chirico reference in the title of the abstract assemblage on the back cover (“Metaphysical view of Factory with album cover”). The Hawklords stage show had Calvert and other performers dressed in the same industrial outfits as the de Chirico-faced figure on the album’s inner sleeve, together with Bubbles’ film footage projected behind the band. These elaborate performances only lasted for a few concerts (see this lengthy post for a more detailed examination of the live PTI concept) which is why the existence of a filmed record of one of the gigs has been tantalising for such a long time.

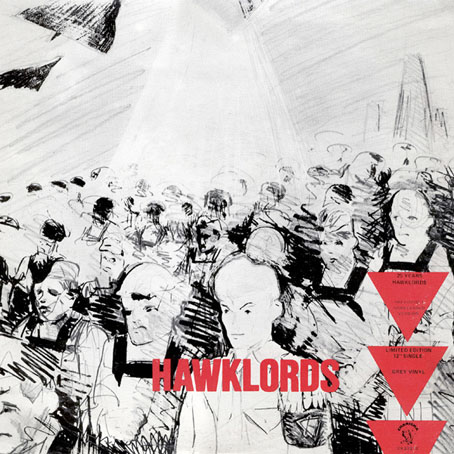

25 Years 12-inch single. Design by Rocking Russian.

So…New Wave science fiction, New Wave design, and even New Wave music on Death Trap and 25 Years (the song), where Calvert’s vocals aim for the delivery of the punk groups. This is especially evident on the live Hawklords recordings where the tempo is faster and Calvert is a lot less restrained than he was in the studio. (The 25 Years promo film ends with faces from British politics and the mass media being flashed on the screen, among them Siouxsie and Sid Vicious.) The 12-inch single continued the album’s dystopian theme with its grey vinyl and sketchy cover art showing some kind of future revolution. The PTI concept may not be very coherent–only four of the album’s eight songs seem to be related to it–but I’ve never been troubled by this, concept albums often work best when they suggest more than they explain. Calvert’s notes for the project are as elliptical as those he wrote for the In Search Of Space “Hawklog” in 1971, and could easily have been run as they were in an issue of New Worlds.

![]()

A Calvert play programme, 1981.

Listening to these albums again provokes my usual mixed feelings about a part of Hawkwind’s history that I just missed experiencing in person. I was 15 in 1977, and remember a boy at school showing off his ticket for the group’s forthcoming gig at Lancaster University. I certainly knew who Hawkwind were–if you were reading science fiction then the Moorcock connections made them impossible to miss–but at the time I hadn’t heard much of their music, so the prospect of seeing them in a distant town was less attractive than it was to become two years later. Robert Calvert left the group in late 1978 after his manic episodes proved too much for everyone while they were on tour. He sings on most of the PXR 5 album but this was essentially a compilation of studio and live recordings recorded before the Hawklords album but only released in mid-1979. I didn’t get to meet Dave Brock until late 1980, by which time the group’s line-up and musical style had changed completely. I did see Calvert a year later, however, in a tiny theatre in Covent Garden, London, where he staged one of his plays, The Kid from Silicon Gulch, a futuristic “electronic musical”. And I eventually got to meet him at another Hawkwind gig in October of that year, backstage at the Hammersmith Odeon. He was very tall, very well-dressed, and seemed very spaced-out compared to how he’d been in the theatre, possibly as a result of the medication he had to take to maintain his mental equilibrium. He later joined the group onstage for a rambling version of Sonic Attack. This was one of the last appearances he made with Hawkwind so it was a fortunate encounter, especially at such a historic venue. But I still wish I’d seen him in his flying gear on that tour in 1977, channelling the zeitgeist while aiming for the stratosphere.

See also:

• Robert Calvert – Hawkwind’s prescient space-rock poet by Joe Banks.

• Hawkwind: Do Not Panic, a BBC documentary from 2007.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Twinkle, twinkle little stars

• Motorway cities

• Reality you can rely on

• Silver machines

• Notes from the Underground

• Hawkwind: Days of the Underground

• The Chronicle of the Cursed Sleeve

• Rock shirts

• The Cosmic Grill

• Void City

• Hawk things

• The Sonic Assassins

• Barney Bubbles: artist and designer

To my non-audiophile ears, these remixes seem very fresh! It’s almost like listening for the first time… Maybe I just haven’t sat down and really analyzed these albums in some time? Either way, there’s a new richness and spatial depth that I’m appreciating now.

’Tis true. Before the big box arrived I spent some time listening to an earlier Cherry Red collection of the same albums. The new mixes definitely sound richer and more detailed. Not sure why that should be but I know from interviews that Dave Brock mixed all the Hawkwind albums up to and including Warrior… while he was dosed on acid. Some of the other Steven Wilson remixes I have in my record collection don’t sound very different at all, although in the case of Tangerine Dream I think the main difference is in the surround mixes for which I don’t have a suitable amplifier.