“This City” (I thought) “is so horrible that its mere existence and perdurance, though in the midst of a secret desert, contaminates the past and the future and in some way even jeopardizes the stars.”

This is the kind of thing I love to find: a BBC adaptation of a story by Jorge Luis Borges which I didn’t even know existed until this week. The Immortal was written in 1947 and published in the fourth collection of the writer’s fiction, El Aleph, in 1949. Anglophone readers will be more familiar with the story from Labyrinths, the most popular Borges collection, and the book I always recommend to those curious about his work. (And with the usual nagging proviso: avoid the Andrew Hurley translations if you can.)

Borges’ immortal is a Roman soldier during the reign of Diocletian whose life is recounted via a manuscript discovered in 1929 inside a volume of poetry. (The volume is Pope’s translation of The Iliad; Homer is never far away in Borges-land, especially in this story.) Disappointed by his military career, the soldier leaves his legion to go in search of the legendary City of the Immortals which is reputed to lie somewhere in the African desert; he finds the city, of course, and also (inevitably) receives more than he bargained for. Borges’ other fictions are seldom as traditionally fantastic as this, although the story’s philosophical musings are enough to set it apart from similar tales, as is the author’s habit of owning up to his recondite literary borrowings, like a magician revealing the secret of a trick at the end of a performance. Even so, The Immortal was generic enough to turn up in an American paperback collection in 1967, New Worlds of Fantasy edited by Terry Carr, along with stories by Roger Zelazny, John Brunner, JG Ballard and others. The Ballard story, The Lost Leonardo, is an uncharacteristic piece about another immortal character, Ahasuerus, the Wandering Jew, cursed to roam the world until the Second Coming of Christ. Ahasuerus was a popular character in the 19th century, whose legend and predicament was enough to sustain Eugène Sue for 1400 pages in a ten-volume historical saga, Le Juif Errant. Borges alludes to Ahasuerus via the name “Joseph Cartaphilus” although this is one obscure reference that he doesn’t explain for the reader. By contrast with the logorrhoeic Monsieur Sue, Borges requires a mere 15 pages to deal with 2000 years of history.

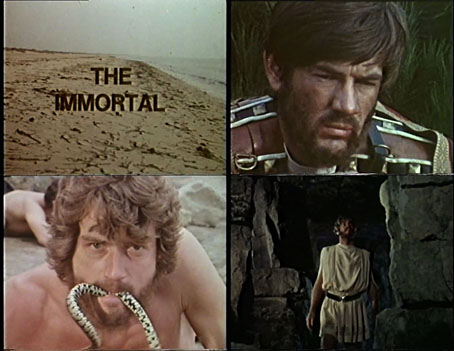

Given the challenges of staging a complex historical drama on a TV budget Carlos Pasini’s film is little more than a 22-minute sketch of its source material, but Borges adaptations are scarce enough that there’s a thrill in seeing the material presented at all, as with the brief dramatisations in the Arena documentary, Borges and I. The Immortal was given a single broadcast on 20th November, 1970, as part of a now-forgotten BBC 2 arts programme, Review, where it was intended as an introduction to the author’s writing following the UK publication of The Book of Imaginary Beings. Mark Edwards plays the Roman soldier whose narration is taken verbatim from the story. Borges’ international reputation had reached a plateau of popularity at this time, after growing steadily during the 1960s. 1970 was also the year that Donald Cammell & Nicolas Roeg’s Performance was released, a film that quotes verbally and visually Borges’ Personal Anthology while also featuring a photo of the man himself. A year later, Michael Moorcock’s first Jerry Cornelius collection, The Nature of the Catastrophe, included the dedication “For Borges”; Jerry Cornelius is another immortal (or timeless) character, one of whose progenitors may be “Joseph Cartaphilus”. Pasini’s adaptation can’t compete with these heavyweights but as a taster of Borgesian prose and ideas it serves its purpose. The director has made it available for viewing here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Borges on Ulysses

• Borges in the firing line

• La Bibliothèque de Babel

• Borges and the cats

• Invasion, a film by Hugo Santiago

• Spiderweb, a film by Paul Miller

• The Library of Babel by Érik Desmazières

• Books Borges never wrote

• Borges and I

• Borges documentary

• Borges in Performance

Borges is one of those authors who seem to be adapted more in spirit to film and television than straightforwardly – the other prime example being Pynchon: I can think of loads of things that are openly Pynchonian, from Repo Man to Lodge 49, but the only actual adaptation I can think of is Inherent Vice. Lem is another – there’s Solaris and the German version of the Ijon Tichy stories, but sly Lemism abounds. Similarly, apart from Alex Cox’s Death and the Compass, I couldn’t think of a single Borges film, despite his running through the popular culture of the last fifty or so years like the name of a seaside town through a stick of rock.

(Less verbosely, thanks for this! I’m sure there are other Borges films, and I’m just ignorant.)

There are a few adaptations but they tend to be rather obscure, as with this example, or made for Spanish speakers which means they aren’t always available in translated form. The most famous one (and very good with it) is Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Stratagem which sets The Theme of the Traitor and the Hero in the Parma region of Italy. There was also a Spanish (or Latin American) TV series, Tales from Borges, made in 1992 which presented several stories: Emma Zunz, The South, Rosendro’s Tale and The Intruder. I saw all of these subtitled on TV but so far the copies that have turned up on YouTube have been without subtitles.

On the subject of Pynchon, I made some suggestion for Pynchonian cinema here: http://www.johncoulthart.com/feuilleton/2021/07/12/pynchonian-cinema/

My understanding is that in the mid-50s during a lull in his literary career Borges himself wrote screenplays. I know no details.

John I’m interested in your comment about the translations of Andrew Hurley. My objection is to the shabby way the Borges estate treated Norman Thomas di Giovanni by rescinding the copyright and suppressing translations that Borges himself collaborated on with Giovanni! Borges has been quoted as preferring some of these translations to the original Spanish versions. Yet they remain out of print. Hurley must share some blame because in the collection authorized by the Borges estate there is no mention of di Giovanni in Hurley’s discussion of previous translations.

Yes, I wrote about one of those films a while ago: http://www.johncoulthart.com/feuilleton/2014/06/11/invasion-a-film-by-hugo-santiago/ I’ve still not watched it since the copies that were available then didn’t have subtitles. Time for another search, I think.

I’ve also linked in the past to a story about the suppression of the Norman Thomas di Giovanni stories. Most of these have been circulating recently as illicit PDFs so the suppression isn’t as thorough as it might have been pre-internet. This seems to be the work of the Borges estate who were reluctant to share copyright with di Giovanni; Hurley was merely doing the job he was paid for in translating the texts. Not as well as previous translators but he wouldn’t have the authority to keep stories out of circulation. There’s a little more on this subject in the post that follows this one!