Art by René Ferracci.

Continuing an occasional series about artworks in feature films. Most people know HR Giger’s work via his production designs for the Alien films; a much smaller number of people also know about his designs for Jodorowsky’s unmade film of Dune, but hardly anyone knows that his art first appeared in a major film two years before Alien was released. This isn’t too surprising when the film in question, Providence, directed by Alain Resnais, has been increasingly difficult to see since 1977; the film isn’t mentioned in any of Giger’s books either, a curious omission for an artist who spent his career logging every public appearance of his work.

Providence began life as a collaboration between Resnais and British playwright David Mercer, with the resulting script leading to a Swiss/French co-production that was filmed in English. The film has an exceptional cast—Dirk Bogarde, Ellen Burstyn, John Gielgud, Elaine Stritch, David Warner—marvellous photography by Ricardo Aronovitch, and a sumptuous score by Miklós Rózsa. If you’re the kind of person who regards awards as designators of quality then it’s worth noting that Providence won 7 Cesar Awards in 1978, including the one for best picture. Yet despite all this, and despite being regularly described as a peak of its director’s career there’s only been a single DVD release which is now deleted. I’d been intending to write about the film for some time but first I had to acquire a decent copy to watch again; this wasn’t an easy task but I managed to “source” a version that was better than the VHS tape I used to own.

For most of its running time Providence is a film about artistic invention, more specifically about the process of writing. Clive Langham (John Gielgud) is an ailing author spending a sleepless night alone in his huge house, “Providence”, wracked by unspecified bowel problems, painful memories and fears of impending death. To distract himself from his troubles he drinks large quantities of wine while mentally sketching a scenario for a novel in which the people closest to him are the main characters. In this story-within-the-story Langham’s son, Claude (Dirk Bogarde), is a priggish barrister whose primary conflicts are with his absent father, his bored wife, Sonia (Ellen Burstyn), and a listless stranger, Kevin (David Warner), who Sonia has befriended and seems attracted to even though Kevin won’t reciprocate. While Claude cajoles and insults the pair he also conducts an affair of his own with Helen (Elaine Stritch), an older woman who resembles his dead mother. The scenario is elevated from being another mundane saga about middle-class infidelities by its persistently dream-like setting, and by the interventions and confusions of its cantankerous author. If you only know John Gielgud from his later cameos playing upper-class gentlemen then he’s a revelation here, boozing and cursing like the proprietor of Black Books. Between spasms of illness and self-pity Langham shuffles his playthings around like chess pieces, revising scenes while trying to keep minor characters from interfering; “Providence” isn’t only the house where Langham lives but also the watchful eye of its God-like author. Meanwhile, his characters bicker and chastise each other, paying little attention to the disturbing events taking place in the streets outside: terrorist bombings, outbreaks of lycanthropy, and elderly citizens being rounded up for extermination.

Resnais plays his own games with the linear structure of the work-in-progress although the scenes aren’t as fragmented as in some of his earlier films. He also plays games with our view of events, continuing a practice begun in Last Year at Marienbad: rooms change their shape, gaining or losing staircases; some of the sets have very artificial backdrops, while the city where all of this takes place is an amalgam of European locations—Brussels, Antwerp—and parts of Providence, Rhode Island. Having been to Providence a few years ago I finally recognised the city when we see HP Lovecraft’s beloved College Hill in a few brief shots. The film was originally going to be made entirely in the US but budgetary restrictions limited the production to Europe.

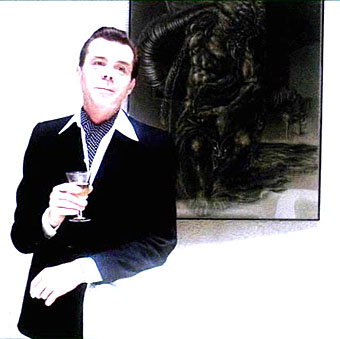

It’s these last details, especially the surprising Lovecraft connection, that lead us to HR Giger…or so I assume since we’re given no explanation for the appearance of his paintings inside Claude and Sonia’s home. The house is as cheerless as their marriage, a labyrinth of dimly-lit marble chambers with all the ambience of a mausoleum; the place is also much larger on the inside than it would appear from the outside, which adds again to the dream-like quality.

The first painting we see isn’t a Giger, however, but a reproduction of a lesser-known work by John Martin, the Romantic painter of Biblical cataclysms. I mistook this one at first for Manfred on the Jungfrau but it’s actually The Bard, a depiction of a scene from the poem of the same name by Thomas Gray which echoes the predicament of the beleaguered Langham: the last Welsh bard is about to fling himself to his death after cursing Edward I and his invading army in the valley below.

The Bard (1817) by John Martin.

It’s this that fascinates me about the use of paintings as references in films: much can be coded into the reference yet it requires recognition from the viewer to make it successful. Books are much easier, and arguably lazier as a result. Even if you don’t know a book title you can look it up later; with a painting you either recognise it or you don’t. As it happens there are a few significant books in this film (it’s a French production, after all): when Sonia sits down in her bedroom we see behind her copies of The Denial of Death and Awakenings by Oliver Sacks. Much later on, Langham is given a copy of a novel by a rival author whose face on the back of the book is that of the film’s own writer, David Mercer.

Li I (1974) by HR Giger.

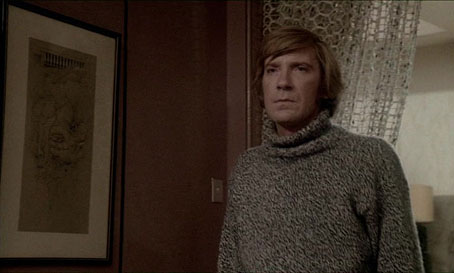

Deeper inside the house we find three Giger prints although they’re never easy to make out in the gloom. Watching the film on TV years ago I could just make out the portrait of Giger’s partner, Li Tobler, which appears in a couple of shots but only clearly in one of them. For a long time I thought this was merely intended as an unusual example of middle-class chic, if not the director’s own taste. I only discovered the Lovecraft/Providence connection very recently; Resnais gave Ricardo Aronovitch copies of Lovecraft’s stories to read as preparation for the film, so we can take the other examples of grotesque art as reinforcing this. By coincidence, Giger’s first major book collection, HR Giger’s Necronomicon, was published the same year the film was released.

Landscape XVIII (1973) by HR Giger.

The other works are Landscape XVIII (1973), one of several pictures Giger produced showing diseased and/or dead babies, and a more typical biomechanical painting, Landscape XXVII (1974), which is only just visible in the shot below.

Landscape XXVII (1974) by HR Giger.

One of the benefits of watching a better copy this time round was being able to make out another picture I’d missed when Kevin wanders past a print by everyone’s favourite Surrealist pornographer, Hans Bellmer. Many of Bellmer’s drawings and paintings are precursors of Giger’s early extrusions of the human figure, especially pieces such as this one.

Untitled print (1965) by Hans Bellmer.

And here’s the biggest surprise of all: two paintings by Sibylle Ruppert, an artist whose work I only became familiar with a few years ago. These are persistently difficult to make out due to the low lighting and reflections on the glass but they’re definitely her work; both Ruppert and Giger are thanked at the end of the film. Ruppert also mentioned her connection with the film in one of her exhibition catalogues.

Le Doute (no date) by Sibylle Ruppert. (The only copies I have of these pictures are b&w scans from a catalogue.)

There’s a further Resnais connection via the screenwriter of Last Year at Marienbad, Alain Robbe-Grillet, whose enthusiasm for Ruppert’s snarling sado-masochistic visions led him to write an appraisal of the artist’s work for one of her exhibitions.

Petite Morte (no date) by Sibylle Ruppert.

Sorry, Dirk, but the picture wouldn’t have been visible otherwise…

I said there’s no reason given for the presence of these paintings but if The Bard is emblematic of Langham’s character—the writer cursing the world in a final gesture of defiance—then the more grotesque pictures might be emblems of his own fears seeping into his creation (the titles of the Ruppert pictures translate as Doubt and Little Death). Deep inside “Providence”, the home, we find a Providence of nightmares.

There’s more I could say about Providence the film but the story changes gear dramatically about 20 minutes from the end so I’m reluctant to spoil things for the curious…that’s if you can find a copy to watch. If ever a film was overdue a blu-ray release it’s this one. And if you ever suspected that reality was the product of an author who wasn’t paying proper attention to his work then take this neglect of a great film as further evidence of the dereliction. I demand a cosmic rewrite.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Art on film: The Beast

• Scarabus, a film by Gérald Frydman

• The Man Who Paints Monsters In The Night

• Les Statues Meurent Aussi, a film by Chris Marker and Alain Resnais

• Toute la mémoire du monde, a film by Alain Resnais

• Marienbad hauntings

• Sibylle Ruppert revisited

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M60Fk_3deCA