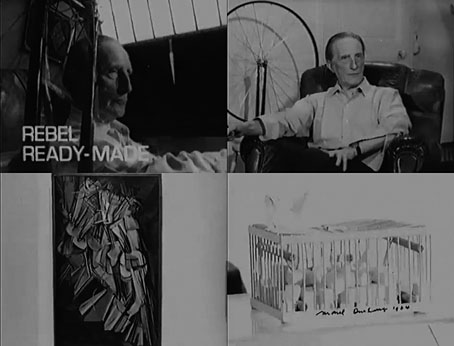

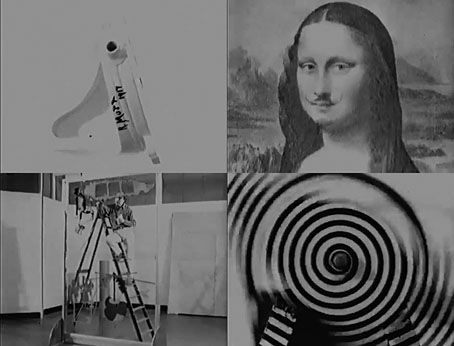

I think I spotted across this one while searching for more Robert Hughes, in which case I offer grudging thanks to the algorithms of the Great Panopticon. If you’ve ever seen Marcel Duchamp talking about his work in an arts documentary then it’s probable that the clip will have been taken from this film. (The Shock of the New is no exception.) Rebel Ready-Made was directed by Tristram Powell for a short-lived BBC arts series, New Release, and broadcast in June 1966 to coincide with a major Duchamp retrospective at the Tate Gallery, London. It’s fascinating for number of reasons, mostly the way that Duchamp is happy to talk about his sporadic art career, an occupation that in its mature phase consisted of spasms of invention followed by increasing boredom and a wandering off to do something else. The ease with which he did all this—the inventions which in other hands would have fuelled entire careers, and then the eventual abandonment of the whole art game—always made a sly mockery of the self-importance that sustained the art world in the 20th century.

Elsewhere in the film you get praise for Duchamp from Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage, plus the artist’s friend Richard Hamilton, seen briefly painting the replica of The Large Glass that appeared in the Tate exhibition as a substitute for the fragile original. This has been my favourite of Duchamp’s works since I saw the replica in the Tate a decade later. Having a duplicate stand in for the original isn’t such an unusual thing for Duchamp when most of his ready-made sculptures are also copies, the “originals” having been lost or destroyed shortly after their first exhibitions. From the 1930s on, Duchamp had also been making multiple copies of all his works in miniature for the various iterations of the Boîte-en-valise, or portable museum.

Tristram Powell was lucky to capture the artist being so talkative at such a late date. Two years after this Duchamp was dead, although there was one last surprise in store. Jasper Johns referred to Étant donné as “the strangest work of art in any museum”. Duchamp never acknowledged the existence of this life-size peepshow while he was alive, preferring it to be announced to the public only after his death, which is what happened in 1969. There are no replicas of this one; if you want to see it (or the parts of it the artist allows you to see) you have to go to Philadelphia and peer through the holes in the door.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Televisual art

• Chance encounters on the dissecting table

• The Witch’s Cradle by Maya Deren

• Audio Arts

• 8 x 8: A Chess Sonata in 8 Movements

• Anémic Cinéma

• Dreams That Money Can Buy

• Entr’acte by René Clair

• View: The Modern Magazine

Thanks for turning me (back) on to the “Shock of the New.” I especially liked Dumas’ frothing-at-the-mouth attack on Gustave Courbet and then Hughes’ deadpan “they don’t write art criticism like that anymore.” It was interesting to re-watch something that I must have originally watched when I was 17, and to realize how pessimistic (not exactly the right word, perhaps despairing?) it was. That whole segment on Brasilia has been rattling around in my head like a piece of angry candy for 42 years.

Here’s an interesting link on the Public Domain Review on Russolo, music technology, Marinetti, fascism. It’s obliquely connected to a previous post on this website about Kraftwerk, musique concrete, and Pierre Schaeffer. https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/luigi-russolos-cacophonous-futures

Thanks, Lionel. I did see that Futurism piece when it was posted, and might have linked to it in one of the weekend posts but I think I avoided it since there were too many links to music stories that week.

The book of The Shock of the New is more negative than the series in some ways since it contains an extra chapter that addresses the rise of the art market in the 1980s; Hughes was always at his most negative when it came to seeing art treated as a mere commodity. But even at his most critical he was always looking out for the contrary examples, people who weren’t simply in it for the money or some short-lived personal glory. You can see that in the American Visions series and The New Shock of the New, the latter being a one-off film he made in 2004 to see how much things had changed since 1979.