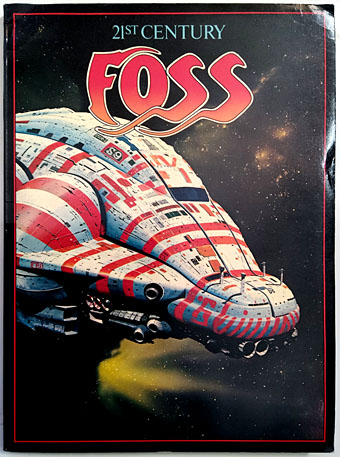

Discovered last week in a local charity shop (and for a fraction of the usual asking price), 21st Century Foss, the Dragon’s Dream collection of Chris Foss paintings from 1978. Foss’s book covers were impossible to avoid in the Britain of the 1970s, often to a ridiculous degree when publishers would stick a spacecraft by the artist or one of his imitators on a book containing no spaceships at all. His ubiquity made him the first cover artist who registered with me as exactly that, an identifiable name whose work suggested that this kind of artistic activity might be something worth pursuing.

I bought a few of the books published by Dragon’s Dream/Paper Tiger in the late 70s/early 80s but many of them weren’t interesting enough to warrant the exhausting of my meagre finances. Ian Miller, yes; Chris Foss, no. Architecture, whether real or invented, was generally more interesting than spaceships, even when the latter were unique designs like the typical Foss behemoth. (There is architecture in many of Foss’s paintings but I preferred Roger Dean’s aesthetics, the fluid and organic buildings, the vehicles modelled on birds, fish and insects.) Foss also suffered from that process of mental evolution whereby you reject an early enthusiasm when you find something that has a more obsessive hold. In musical terms, his paintings were like glam pop, the first music that made a deep impression but which was swiftly displaced by progressive rock and electronic music. Despite the repudiation I still get a weird charge when I see one of his paintings, an instant jolt back to an adolescent mental space. His cover for Midsummer Century by James Blish does this to an excessive degree, being one of a handful of Foss pictures that caused me to attempt some imitative drawings of my own circa 1975. Those drawings, which went astray years ago, caused a minor stir of appreciation among schoolfriends, a reaction that made me realise I was doing something right, however amateurish the attempt.

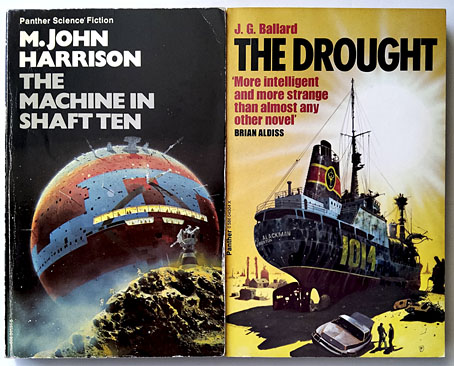

Ballard’s Low-Flying Aircraft collection is labelled on the rear as “Fiction”, and is spaceship-free, whatever the cover may suggest.

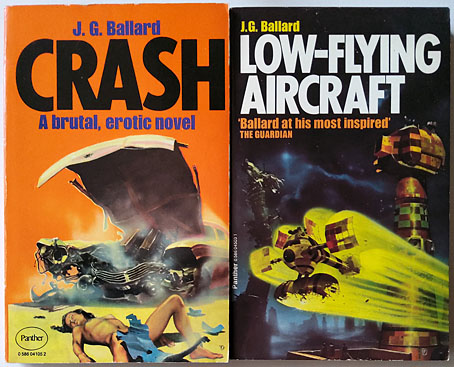

21st Century Foss belies its title by being more than a simple parade of spacecraft designs. There are Foss covers that you never see in internet galleries—pictures of submarines, ships and aircraft from the Second World War—together with a few pieces used on the covers of crank titles. Ballard aficionados may like to know that the cover for the Panther paperback of Crash is reproduced here on a full page. The latter is a good example of the thinking in paperback publishing at the time: “Ballard is science fiction so we need an SF artist for this one!” Foss had earlier illustrated two volumes of The Joy of Sex so must have seemed an ideal match. According to Rick Poynor, the artist hated the novel while the author disliked the cover.

Foss’s book opens with a section about his designs for three feature films: Jodorowsky’s Dune, Superman and Alien. None of his concepts ended up on the screen but it’s good to see the Dune designs in print. This section is also prefaced by two pages of hyperactive hyperbole for Foss and his art from Alejandro Jodorowsky. The same text may be found at Duneinfo but it bears repeating here as a further example of the manic director in full flight. Incidentally, the “English magazine” that’s referred to is most likely Science Fiction Monthly for February 1974, an issue which contained a collection of Foss paintings plus an interview with the artist.

* * *

Jodorowsky on Foss

Dune had to be made.

But what kind of spaceships to use? Certainly not the degenerate and cold offspring of present day American automobiles and submarines, the very antithesis of art, usually seen in science fiction films, including 2001. No! I wanted magical entities, vibrating vehicles, like fish that swim and have their being in the mythological deeps of the surrounding ocean. The ‘galactic’ ships of North American technocracy are a mouse-gray insult to the divine, therefore delirious, chaos of the universe. I wanted jewels, machine-animas soul-mechanisms. Sublime as snow crystals, myriad-faceted fly eyes, butterfly pinions. Not giant refrigerators, transistorised and riveted hulks; bloated with imperialism, pillage, arrogance and eunuchoid science.

I affirm that next to the soul the most beautiful object in the galaxy is a spaceship! We all dreamed of womb-ships, antechambers for rebirth into other dimensions; dreamed of whore-ships driven by the semen of our passionate ejaculations. The invincible and castrating rocket carrying our vengeance to the icy heart of a treacherous sun; humming-bird ornithopters which fly us to sip the ancient nectar of the dwarf stars giving us the juice of eternity. Yes! But far more than that: angelic splendour! We dreamed of caterpillar-tracked hotrods so vast that their tails would disappear behind the horizon. We saw ourselves enmeshed in these huge masses hurtling a dizzy train of planets from a dark world bound for a galaxy drowned in starry milk. We saw ourselves inside minute ether-dwelling sharks crossing seven thousand universes in one Terrene second, leaving a sound-wake freezing into a trail of hallucinatory pearls. Trains to carry away the whole of humanity; machines greater than suns wandering crazed and rusted, whimpering like dogs seeking a master. And great wings sucking the marrow of comets. And thinking wheels hidden behind meteorites, waiting, camouflaged as metallic rocks, for a drop of life to pass through those lost galactic fringes to slake thirsty tanks with psychic secretions. All this and more I wanted for Dune.

Then, suddenly, in a bookshop in the pages of an English magazine I found splashed in a thousand colours what I had believed impossible to depict. These spaceships that pleased and moved me were Chris Foss’. I covered the studio walls where I was preparing the film with his works. All masterpieces. I hired various sleuths to track him down. You see, in those heady days I had power! I had a multi-million dollar commitment behind me: a commitment that remained unfulfilled. I had it in my power to call upon the best brains of our generation to collaborate on a project that was to give a messiah to the world. Not a human being, but a film. A film that would be our master. Dune had made me its apostle; but I needed others, and one of these was Chris Foss.

What the hell would this mutant be like? Because he had to be a mutant to draw like that! These were not drawings. They were visions! Would he be some neurotic old man? A maniac drug addict? Would one be able to talk to him? Then Chris Foss turned up, completely English with his tap-dancer’s shoes, his tight suit as worn by Casanovas in sophisticated dives, with a tooth of quick-gold (I thought it was a diamond), with a yellow shirt of imperial silk, the blinding tie of an aesthetic hit-man, with a child’s smile so penetrating he could turn into a hyena. Yes: Chris Foss was a true angel, a being as real and as unreal as his spaceships. A mediaeval goldsmith of future eons; a being who carried his drawings with the same ultra-maternal care as the Kaitanese Kangarooboos carry the children born of their self-insemination.

Chris arrived very nervous and mistrustful. He was afraid that we would impose a style on him, that we would limit him. But when he realized that he had total freedom he fell into ecstasy. He bought himself a special glass drawing-board which made his paper transparent, so that the lines seemed to float in space. And he plunged into his work for hours, millennia. He would go for long walks in the small hours to a little plaza where lepidopterous creatures with human skin and prehistoric perfumes would entwine their pink tongues with long, transparent hairs around his British member. I also saw him slake his physicoemotointellectuometaphysical thirst with alcohols seeping like tears from eyes slashed open in the aggressive air of a hotel corridor.

And thus were born the mimetic spaceships, the leather and dagger-studded machines of the fascist Sardaukers; the pachydermatous geometry of Emperor Padishah’s golden planet; the delicate butterfly plane and so many other incredible machines, which I am sure will one day populate interstellar space. Chris Foss knows that today’s technical reality is tomorrow’s falsehood. Chris also knows that today’s pure art is tomorrow’s reality. Man will conquer space mounted on Foss’ spaceships, never in NASA’s concentration camps of the spirit. I was grateful for the existence of my friend. He brought the colours of the apocalypse to the sad machines of a future without imagination.

Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1977

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Crank book covers

• The artists of Future Life

• Science Fiction Monthly

• Roger Dean: artist and designer

• Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune

• The art of Ian Miller

There is a reworking of the Foss cover for Ballards Crash by the Chapmans on their “homage” to Ballard, Crash Bang Wallop by J & D Ballard (Jake & Dinos Chapman). It’s not that great, but maybe if minor interest.

Foss’s cover for alpha 1, edited by Robert Silverberg, depicting a gigantic vacuum cleaner-like structure rearing up from the surface of some alien planet, immediately jolts me back to my own adolescent mental space in the same period. I also remember Foss’s covers for the E. E. “Doc” Smith Lensman series, which my dad also had along with the Silverberg anthology, but unlike alpha 1, those books proved to be unreadable.

“…an instant jolt back to an adolescent mental space.”

I’m with you there, compounded for me with a vague memory of associated physical space, the default site for me being the SF book section of WH Smiths in Rochdale’s Arndale, a micro-gallery of Foss and his many imitators.

It’s never occurred to me before but, given the ties of Dragon’s Dream to the Deans, is the ‘FOSS’ on the cover Roger’s work?

Anthoney: Thanks, I seem to recall hearing about that but I’m generally underwhelmed by the Chapmans’ works so didn’t pay it much attention.

AIBlyth: I was the same with many of the books with Foss covers, few of them were of interest, the Lensman books (and James Blish) included. I have another Ballard Foss (The Drought), and a Harlan Ellison collection, and I think that’s all.

PaulK: It was Smiths in Blackpool for me, not a large shop but very important at the time.

I think Dean did most of the title designs for the Dragon’s Dream books, and some of the later Paper Tiger titles. I always think he’s underrated as a lettering designer despite his style being so recognisable.

Great essay! Love learning a bit about Foss, and you’re evolving feelings about his art weirdly mirror my evolving feelings about Jodorowsky’s tarot teachings.

“he’s underrated as a lettering designer”…

He’s suffered from being so recognizable and so tightly associated with “prog” and its perceived problematics/ponderousness. The best testament to his skill is to look at how far short any attempt to copy his style always seems to fall: Venom’s early logo, Boris (I think you wrote about that one), Tism…well, that and the pencil work reproduced in Views.

Yes, I made a post about the Dean-plunderings of Boris. I can testify to the difficulty of imitating the Dean lettering style since I tried that enough times myself in my youth. The anti-prog prejudice is definitely one reason why he gets ignored as a designer (something I explored in another post) but he doesn’t catch the attention of type designers either since the titles are usually unique designs, not whole typefaces.

I’ve always loved Foss’s cover for James Blish’s Midsummer Century:

https://raggedclawsnetwork.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/chris-foss_midsummer-century_london-arrow-1975.jpg

Yeah, I did link to that one in the post…

Re. the Chris Foss book cover for J.G. Ballard’s The Drought:

Paint is cracked and dry

The name is now illegible

And everything is lost upon the cracked and misted hull

Beneath a yellow sky

The lovers trip beside a ship

But all I hear when they embrace is just the kiss of skulls

From “Insanely Jealous”. The Soft Boys, Underwater Moonlight (1980). Presumably written by Robin Hitchcock

Thanks, John. The Burning World by Swans can be taken as alluding to The Drought but only if you know that The Burning World was the name of the novel in the US.