“MAGIC REALISM • Like the video technique of “keying in” where any background may be electronically inserted or deleted independently of foreground, the ability to bring the actual sound of musics of various epochs and geographical origins all together in the same compositional frame marks a unique point in history. • A trumpet, branched into a chorus of trumpets by computer, traces the motifs of the Indian raga DARBARI over Senegalese drumming recorded in Paris and a background mosaic of frozen moments from an exotic Hollywood orchestration of the 1950’s [a sonic texture like a “Mona Lisa” which, in close up, reveals itself to be made up of tiny reproductions of the Taj Mahal], while the ancient call of an AKA pygmy voice in the Central African Rainforest—transposed to move in sequences of chords unheard of until the 20th century—rises and falls among gamelan-like cascades, multiplications of a single “digital snapshot” of a traditional instrument played on the Indonesian island of JAVA, on the other side of the world.” — Jon Hassell

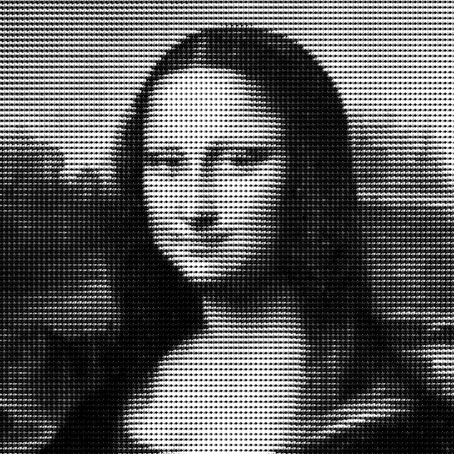

Jon Hassell’s text is part of the sleeve note for his Aka—Darbari—Java (Magic Realism) album which was released on Editions EG in 1983. The description of a picture of the Mona Lisa made from tiny reproductions of the Taj Mahal always intrigued me even though it’s only a shorthand metaphor for the sampling process, as well as being an encapsulation in miniature of one aspect of Hassell”s “Fourth World” concept: the blending of East and West, the sacred and the profane. Nevertheless, 20 years ago—17th May, 2001, according to the date on the file—after realising that Photoshop allowed the creation of just this kind of mosaic imagery, I decided to try and bring Hassell’s metaphor to digital life.

The end result in its full-size version looks at a distance like an ordinary halftone rendering of the painting but it really is made of tiny images of the Taj Mahal, albeit very rough ones since the process always resulted in a bitmap image. So much time has elapsed I’ve forgotten the procedural details although I do recall the involvement of one of those legacy features of Photoshop that most people ignore, possibly the Apply Image function. And I only did this at all because I’d found a tutorial somewhere that described how to create a mosaic image in this manner. The resulting picture wasn’t particularly satisfying but as a proof of concept it did at least work.

Plenty of tools exist today for making photo mosaics although the results are unsatisfying in other ways. The picture below is the result of images from Wikimedia Commons having been run through one of the many online photo mosaic creators. The online tool doesn’t modulate either of the images very much but seems to map the smaller image across the larger then adjust the brightness and transparency to match the equivalent values of the larger picture. The ideal version of this image—if such a thing had to exist at all—would be one created by a more sophisticated computer process, or a painting, something very large done in the hyper-real manner of Salvador Dalí or Hassell’s friend, Mati Klarwein, whose Soundscape painting occupies the front cover of Aka—Darbari—Java. Or maybe an animated zoom out of the Mona Lisa‘s face would be better, like the one in The Public Voice by Lejf Marcussen.

The Aka—Darbari—Java album is the most strikingly original entry in Hassell’s discography. In 1983 it sounded very avant-garde, and continued to sound that way until well into the 1990s when electronic musicians were beginning to catch up with Hassell’s innovations. It wasn’t the first album to use Fairlight samples as a compositional tool but most of the people using the Fairlight in the early 1980s were still working in a rock/pop idiom, and many of them were using the instrument merely as another big and very expensive keyboard. The reputation of Hassell’s album would be greater today if it hadn’t been unavailable since 1991, one of the last albums to remain marooned by the collapse of the EG label and the ensuing tangle of company purchases. Copies of the album command increasingly high prices on Discogs so it’s worth noting that Burning Shed still have remaindered vinyl copies available for a lot less than the secondhand discs that dealers are selling.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Sounds off the Beaten Track

• Jon Hassell, 1937–2021

• Jon Hassell, live 1989

• Power Spot by Michael Scroggins

just a question, wasn’t this methodology used for good results by H. zukay already in the ’70?

Hassell and Czukay’s recordings have superficial similarities–and they both appeared together on the Music And Rhythm compilation as well as on David Sylvian’s early recordings–but the process, intent and outcome is very different. (I’ve got most of Czukay’s albums, and put together a mix of some favourite tracks a while ago.)

Hassell had a serious conceptual/philosophical stance while also always working towards music that was texturally rich and un-cerebral, able to embrace improvisation. Czukay, by contrast, was often simply playing around in the studio, and almost all of his work has some kind of rock rhythm, something that Hassell tended to avoid, especially on his early albums. The Canaxis album that Czukay made with Rolf Dammers combines orchestral tape-loops with a recording of Vietnamese singers but it’s a relatively simple juxtaposition, like the African Sanctus album that David Fanshawe recorded a few years later. Czukay’s Movies album is a huge favourite of mine but the Persian Love track is a fairly standard rock composition overlaid with singers recorded from the radio. It’s brilliantly done, as is everything else on that album, but the two elements of the recording remain separate things. Hassell on Aka–Darbari–Java was attempting an integration of all the separate elements to create what he calls elsewhere in that sleeve note a “coffee-coloured classical music of the future”. I think the closest Czukay gets to this is on Mirage from his Good Morning Story album, a rhythmless soundscape made from layered samples.