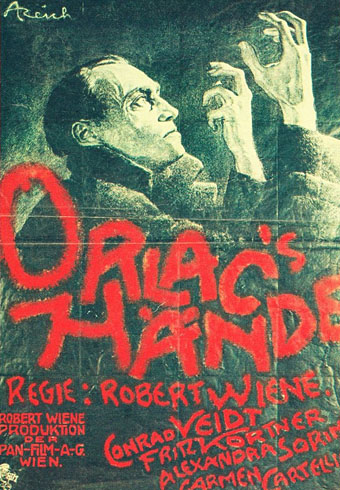

My weekend viewing included two films based on The Hands of Orlac (1920), a novel by Maurice Renard. This is one of those books that remains little read and seldom discussed even though its central idea—a concert pianist injured in a train wreck is given the hands of an executed murderer in a transplant operation—has prompted many film adaptations, almost enough to make the novel the origin of a sub-genre of hand-transplant horror. Robert Wiene’s The Hands of Orlac was the first screen adaptation made in 1924, and is another in the long list of silent films I’ve known about for decades but had to wait until now to see. The film is notable for reuniting the director of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari with Conrad Veidt, the actor who portrayed Caligari’s murderous somnambulist, Cesare, in a mute role that mostly required stalking around acutely-angled sets in a black body stocking.

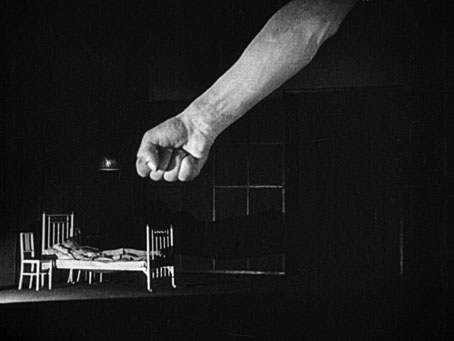

The Hands of Orlac: Paul Orlac (Conrad Veidt) is besieged by nightmares in his colossal hospital room.

Veidt has much more to do as the lead in The Hands of Orlac, giving a suitably tormented performance as the pianist convinced that his new hands retain the violent impulses of their former owner. The acting from Veidt and Alexandra Sorina as Orlac’s wife, Yvonne, is often wildly emotive, surprisingly so for a film made near the end of the silent era when the mannerisms of early silent pictures were being replaced by greater naturalism. Lotte Eisner in The Haunted Screen explains this in terms of the Expressionist influence which was still prevalent in German cinema, and which extends beyond lighting and set design. A scene in which Orlac is overwhelmed by his predicament is described by Eisner as “an Expressionist ballet”; when Orlac holds a dagger aloft this becomes an unmistakable mirroring of a climactic moment in Caligari.

The Wiene film is a new blu-ray release from Eureka which I was pleased to see at long last although the restoration by the Film Archive of Austria comes with a newly-commissioned score which I wasn’t pleased with at all. The general form when a new score has been written for a silent film is to give the viewer a choice between a fresh recording of the original music (if the score still exists) and the new score. The FAA print offers no such choice. The new music seems to be the work of composer Johannes Kalitzke although I’m having to guess this since—surprisingly—neither the film print or the disc packaging identifies the composer. Kalitzke’s score (if it is his work) is the kind of shrieking, clattering atonal fare that I wouldn’t mind listening to on its own but which operates here with little or no sympathy for the unfolding drama. I persevered with it for 15 minutes before muting the sound and using the score for I Am Here by Jóhann Jóhannsson & BJ Nilsen instead, something that worked remarkably well for a choice made in haste. On the plus side, the Orlac set design is impressively cavernous, with the severe angles and shadows of Caligari replaced by Art Deco lines and curves. The Eureka disc also offers a different print of the film in lesser quality (and with a different score), while the booklet notes include an essay by Tim Lucas which reclaims Maurice Renard as a pioneer author of body horror.

Mad Love was shown as The Hands of Orlac in Mexico, Spain, the UK and elsewhere.

Angles and shadows are omnipresent in the second adaptation of Renard’s novel, Mad Love (1935), which I had seen before but hadn’t watched for a very long time. This one deviates wildly from its source, and becomes increasingly preposterous as it goes on, but it’s still a lot of fun. The main attraction is Peter Lorre in his first Hollywood role as Dr Gogol, a transplant surgeon with a bald head and an escalating erotic mania, but I was watching it this time for traces of Guy Endore’s hand (or hands) in the script. Endore’s initial draft was rewritten, with the final credit going to John L. Balderston, but I’d guess that Endore is responsible for the many literary references, touches which are absent from Balderston’s other scripts. The very un-French name “Gogol” is the most obvious one but the dialogue also refers to Greek mythology, and quotes from the poetry of Oscar Wilde and Robert Browning. A brief medical discussion paraphrases psychoanalysis—one of Endore’s interests—while the Grand Guignol scenes that open the film are the kind of thing you’d expect from the author of The Werewolf of Paris and a biography of the Marquis de Sade.

If you cross Peter Lorre’s child killer from M with the bald-headed Dr Gogol you get Kurt Raab as Fritz Haarman in The Tenderness of Wolves (1973).

Karl Freund’s direction in Mad Love is less of an attraction than the performances or the script. Freund had been a major cinematographer for the German studios—he photographed Metropolis for Fritz Lang and The Last Laugh for Friedrich Murnau—but his work here is indistinguishable from any other journeyman director of the period. Mad Love was his last feature after which he returned to cinematography. Peter Lorre, meanwhile, had a date with an amputated hand a decade later in The Beast with Five Fingers, Robert Florey’s adaptation of the classic horror tale by William F. Harvey. Florey’s film is another one I’ve not seen for a very long time and which is now on the future viewing list.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Sympathy for the devil

• Satan’s Saint

• Psychotronic Video

• In Germany before the war

I love both of those; ‘The Simpsons’ did an amusing skit on it years ago (when it was still funny) in a ‘Treehouse Of Terror’ segment called ‘Hell Toupee’ in which Homer is compelled to commit crimes following a hair transplant made from the posessed quiff of an executed criminal.