“But it is a curve each of them feels, unmistakably. It is the parabola. They must have guessed, once or twice—guessed and refused to believe—that everything, always, collectively, had been moving toward that purified shape latent in the sky, that shape of no surprise, no second chances, no return. Yet they do move forever under it, reserved for its own black-and-white bad news certainly as if it were the Rainbow, and they its children….”

Reader, I read it. It isn’t an admission of great achievement to announce that you’ve reached the last page of a novel after a handful of stalled attempts, but when it’s taken me 36 years to reach this point it feels worthy of note; and besides which, Gravity’s Rainbow isn’t an ordinary novel. Umberto Eco is partly responsible for my return to Pynchon. I’d just finished The Name of the Rose, a book I’d avoided for years even while reading (and enjoying) a couple of Eco’s other novels, and was wondering what to read next. Maybe it was time to try the Rocket book again? The thick white spine of the Picador edition—760 pages in 10pt type—would accuse me every time I spotted it on the shelf: “Still haven’t made it to page 100, have you?” For many people this happens with novels because a book is “difficult” (which I didn’t think it was), or boring (which it isn’t at all), or simply too long (page count doesn’t put me off). Back in 1985 I was looking for more heavyweight fare after reading Ulysses, something I’ve now done several times, so I wasn’t going to be intimidated by a novel which is misleadingly compared to Ulysses on its back cover. If anything the comparison was an enticing one. Pynchon at the time exerted a gravitational pull (so to speak) for being very mysterious, although this was a decade when most living authors, especially foreign ones, were mysterious to a greater degree than they are today, when so many have their own websites and social media profiles. Pynchon’s works were also referred to in interesting places, unlike his less mysterious contemporaries. I may be misremembering but I seem to recall a mention of the W.A.S.T.E. enigma from The Crying of Lot 49 in Robert Shea & Robert Anton Wilson’s Illuminatus!; if it is there then it’s no surprise that a writer so preoccupied with conspiracy and paranoia would find favour with the authors of the ultimate conspiracy novel. (And that’s not all. I’m surprised now by the amount of coincidental correspondence between Illuminatus! and Gravity’s Rainbow. Both novels were being written at the same time, the late 1960s, yet both refer to the Illuminati, the eye in the pyramid on the dollar bill, Nazi occultism, and the death of John Dillinger. Both novels also acknowledge the precedent of Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo, another remarkable conflation of conspiracy, secret history, and wild invention.)

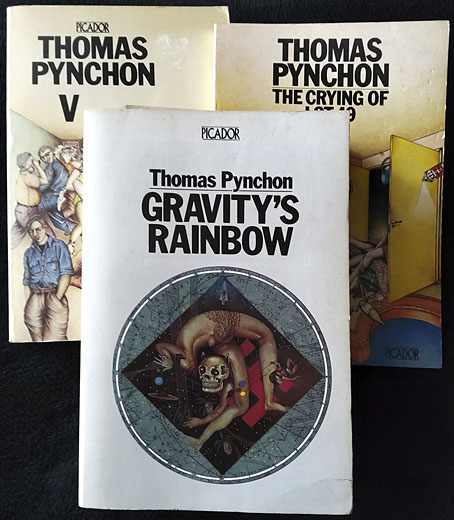

Pynchon had other connections to the kind of fiction I was already interested in. One of his early short stories, Entropy, had been published in New Worlds magazine in 1969, although editor Michael Moorcock later claimed to have avoided reading any of the novels until much later. And, Pynchon, like Shea & Wilson (and Moorcock…), made pop-culture waves. I think it was Laurie Anderson who put Gravity’s Rainbow in the centre of my radar when she released Mister Heartbreak, an album whose third song, Gravity’s Angel, refers to the novel and is dedicated to its author. As for the novel itself, in the mid-1980s this was still Pynchon’s major work, the one that fully established his reputation. Nothing new had appeared since its publication in 1973; Vineland, and the subsequent acceleration of the authorial production line, was six years away. The final lure was the refusal of the Picador edition to communicate very much of its contents: what was this thick volume actually about? The back cover is filled with praise but doesn’t tell you anything about the novel at all, while the cover illustration by Anita Kunz suggests a scenario connected with the Second World War but little else. (“This was one of the most complicated books I ever read,” says the artist, “and really hard to get the germ of the idea. Pynchon kept going off in tangents. I mixed up the art the same way the writer did and made an image that can be read in all directions.”) It’s only when you start reading the book that you find the connection between the novel’s dominant concerns—the development of the V-2 rockets used by the Nazis to bomb London, and the erotic compulsions of Tyrone Slothrop, an American lieutenant at large in war-ravaged Europe—subtly reflected in the illustration, much more subtly than the cover art on the edition that preceded this one.

So given all of this, why couldn’t I get through the damned thing? Bad timing and lack of patience for the most part. Every time I gave it another try I quickly grew tired of the digressions which start early on and continue throughout the first 170 pages. As Anita Kunz says, the novel digresses continually, especially in part one, like a dream that keeps changing focus, wandering into the past or following a loose end prompted by the memory of a minor character. This is often very entertaining—eg: a page-long speculation that the balls in pinball machines are alien lifeforms exiled from their silver planet, doomed to be knocked around gaming tables for the duration of their lives—but I kept finding the whole thing exasperating. In 1985 I’d just started reading through the works of Jorge Luis Borges, an author who preferred to condense his ideas into short stories and essays. Gravity’s Rainbow on the first attempt lost out to my eagerness to return to Jorge. The irony is that Borges is mentioned twice in the novel but I never read far enough to be surprised by the encounter.

Pynchon’s narrative voice was the other stumbling block, although here again, it’s more welcoming for a contemporary reader than that of James Joyce. I never seemed to be in the mood for the erratically humorous tone which is a feature of a book that isn’t really a comic novel as such, despite many overtly comic episodes. The character names in the first part of the novel—Teddy Bloat, Edwin Treacle, Blodgett Waxwing—are of a type you’d expect in a Spike Milligan script, even when the events the characters are experiencing aren’t amusing at all. Eccentric nomenclature is an old literary device, of course, but you can usually sense a rationale at work. (And yet…sometimes there is a rationale at work. This is a novel that makes its own rules.) The wackiness extends to the picaresque storyline, at least in the Slothrop episodes; the deeper you get into the novel the more it veers from the comic to the serious, a dynamic that’s also a feature of Pynchon’s debut novel, V. One of the many things we learn in the author’s first novel is that he’s a jazz aficionado; one of the few things we know for certain about the author is that he likes the pistol-wielding Spike Jones enough to have written the booklet notes for a compilation of the City Slickers’ noisy deconstructions of popular tunes. (Check out some of the band members’ own wacky names: Sir Frederick Gas and Dr Horatio Q. Birdbath.) In the absence of other detail this tells us something about Pynchon’s own character: he stands in relation to all that literature stuff the way that Spike Jones and co. do to all that jazz. Part of the time, anyway…. (Ending paragraphs with an ellipsis is another Pynchon tic.)

Robert Crumb, 1970.

A more pertinent comparison occurred to me while writing the above: underground comics. Gravity’s Rainbow is set in the late 1940s but the drug consumption in the novel reads like something from 20 years later. The drug references extend to character names: a German dealer is named “Bummer”, while a contraband smuggler is “Frau Gnahb”. “Bhang”…geddit? Pynchon even manages to work in a mention of a new substance being made at the Sandoz laboratories in Switzerland, something that the chemists have called “LSD”. And he likes comics enough to have Slothrop reading an issue of Plastic Man, fittingly one of the wackier comic-book characters of the time. Later on, the AWOL lieutenant is running around the ruins of Berlin in the guise of the self-styled “Rocketman”, complete with cape and helmet, on a mission to retrieve a large quantity of buried hashish. All of this caused Gravity’s Rainbow to come immediately to mind when I happened to be flipping through some of the early undergrounds: there inside Hydrogen Bomb and Biological Warfare Funnies (1970) is Robert Crumb as “Mr Sketchum” saying the words “Oboy oboy”, a very common Crumbism, and an expression that Slothrop uses throughout the first half of the novel. In the same issue, Gilbert Shelton’s superhero parody, Wonder Warthog, appears in a long story, The Pigs from Uranus; Slothrop’s Rocketman has a lot more in common with the Hog of Steel than with any of the costumed bores you’ll find in more prominent titles. Elsewhere, the first story in Crumb’s Your Hytone Comics (1971) has a depressed plumber flushing himself down a toilet which leads to a journey through a sewer rather like the one taken by Slothrop during an extended hallucination. Pynchon is as gleefully scatalogical as the underground artists can be, something that apparently upset the delicate sensibilities of the Pulitzer Prize committee in 1974. I’m not suggesting that Pynchon has been influenced by underground comics, or that he’s even seen any of these obscure titles. But Gravity’s Rainbow would have made more immediate sense to me in 1985 if I’d had the sense myself to read it as literature filtered through the same irreverent and absurd sensibility that you find in the undergrounds, that combination of sex, drugs, taste-free humour, flights of fantasy, general weirdness and unrestrained physical detail. Also useful would have been Pynchon’s introduction to his story collection, Slow Learner, in which he acknowledges Surrealism as an influence on his early writing, together with a surprising fondness for the novels of John Buchan. The Buchan enthusiasm is evident in the roller-coaster nature of Slothrop’s adventures, as well as Pynchon’s grasp of English character traits. Spike Jones, underground comics, Surrealism, John Buchan…and a relentless parading of technicalities that you might expect from someone if they’d swallowed the entire Encyclopaedia Britannica: Propaedia, Micropaedia and Macropaedia.

All of this is self-evident in retrospect, something that wouldn’t have been the case several weeks ago. So this time, rather than leap in unprepared I decided to first try reading the author’s earlier novels, V and The Crying of Lot 49, the latter being the only Pynchon I’d read before. This proved to be a good idea, and it’s a procedure I’d recommend to anyone else with an urge to follow Slothrop’s progress. Reading the three novels in sequence not only attunes you to the idiosyncrasies of the Pynchon style but also alerts you to the connections between the novels. Two characters from V turn up in Gravity’s Rainbow, while the chapter in V that concerns the (real) genocidal activities undertaken by German colonialists in South-West Africa in the early 1900s leads to the (fictional) Schwarzkommandos of Gravity’s Rainbow, a group of transplanted Herero Africans working for the Nazis on the V-2 project while secretly planning to take the rocket technology back to Africa. V even mentions the V-2, as does The Crying of Lot 49, a minor work that Pynchon later dismissed but which has its own merits. The travails of Oedipa Maas are like a dry run for Slothrop’s adventures, albeit on a much smaller scale, with a similar combination of technocratic conspiracy and escalating paranoia.

Did I enjoy Gravity’s Rainbow? Yes, I did, very much. I get it now, Mr Ruch and all you Pynchon-heads, “I’m hep,” as Seaman Bodine would say. Would I recommend it? Yes, I would, if any of the above has piqued your interest. I ought to emphasise that none of my complaints should be taken as a demand for authors to do anything other than write what they want in the manner they prefer. If a reader doesn’t like the results there are plenty of other novels out there that won’t lead you down rabbit holes (or sewers) filled with giant adenoids, pinball aliens and sentient lightbulbs.

“Curiously enough, one cannot read a book; one can only reread it. A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader.” —Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature.

Nabokov was delivering his literature lectures at Cornell University while Pynchon was a student there. He’s right about rereading but it isn’t so easy when you’re also eager to dive into something new. Gravity’s Rainbow is complex and detailed enough to warrant another immersion but for now I’m continuing the binge with Vineland. And after that, two more heavyweight volumes await: Mason & Dixon and Against the Day. And then there’s Inherent Vice which I really ought to have read before I watched the film. This may take some time….

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Pynchon and Varo

• Thomas Pynchon – A Journey into the Mind of [P.]

Great insight linking Pynchon with the late sixties underground comics. Same sensibility that came up through that post-Beat/Sick humor/Dr. Strangelove/Terry Southern sensibility.

Side note: I’ve always wanted somebody to put out an album of all of Pynchon’s songs (which are even more numerous than Tolkien’s), especially The Paranoids’s tracks in Lot 49.

https://thomaspynchon.com/thomas-pynchon-inspired-music/3/

As erudite a view of G.R. as I’ve read anywhere. The contemporary links embed it squarely in an almost mythical America…

If you are up for another rewarding challenge – Fuentes Terra Nostra took me a decade. Nine years spent repeatedly attacking the first chapter and then an exhilarating month gorging on the rest.

Also Hallucinations by Reinaldo Arenas, less width more breadth ….

Hecubot: Heh, yeah. I’d forgotten all about The Paranoids until I read the novel again. There haven’t been any songs in Vineland so far. There are a couple of bands in the story but one is a surf group (so mostly instrumental) and the metal band in the novel’s present hasn’t yet had their lyrics revealed.

I didn’t want to labour the speculations about the writing of Gravity’s Rainbow but Pynchon was living in Southern California at the time–in the 2002 documentary about him they track down his house–so he would have had easy access to all the comix coming out of San Francisco. I thought it worth mentioning since other analyses of the novel will be much more oriented towards the literary. I’d be very surprised if he didn’t like Crumb’s strips.

Hi Paul! I’ve still not read any Fuentes but thanks for the tip. And I’d not heard of the Arenas until you referred to it in the title of one of your tracks. One Hundred Years of Solitude is another unread Picador paperback radiating its accusation on the shelf. And I still haven’t got through Cortázar’s Hopscotch although I’ve read some of his short stories. It’s the read/reread issue again: I’m often rereading Borges when I might be reading something new.

GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (curiously enough, my copy is also a Picador, albeit a later printing) sits on my shelf patiently awaiting the day that it will be read. Occasionally I reread Borges, too, but the guilty sensation that I should be reading something new always creeps upon me. Discounting short stories, the last book that I re-read was Sarban’s THE DOLL MAKER last May, although I had not read it for five years, then. I promised myself, nearly five years ago, that I would read Alan Moore’s JERUSALEM and Roberto Bolano’s 2666, but other, shorter books have taken precedence. The other longer novels on my shelves include ULYSSES, FINNEGAN’S WAKE, A GLASTONBURY ROMANCE, and HOPSCOTCH (I am currently reading Cortazar’s short stories, which I am almost done with), none of which I have read, yet, but, time-wise, short stories are usually always easier, hence a certain reluctance, coupled with excitement, that I may feel when I plunge into these works.

I do not read a lot of comic books, myself, but I have great respect for artists who utilise the medium. Cortazar, I think, wrote one such strip, as did Dino Buzzati, the next author on my infinite to-read pile.

I don’t mind length if a book is interesting, I’ve breezed through Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet (880 pages) and Avignon Quintet (1360 pages). I’ll definitely read the Quartet again. A friend keeps insisting that I read 2666 but I’ve yet to read any Bolaño.

From one minor reader to anyone else – I’ve found that when approaching a Big Book it’s best to buy or order 2 copies, save the one in better condition for the shelf (to impress others and one’s memory) and cut the other copy up into easily readable sections (even better if you can find a used copy to dissect) – easier to hold, easier to digest – somewhat like the old days of the three volume novel, or Dickens coming out in installments – it’s amazing how quickly you can go through and with what attention you can give the nicely divided sections – like paring an apple or taking an orange apart – it also removes any tension one might have about breaking the spine, making notes or drawing on the pages as you go along … and may in the end eliminate any unnecessary rereading …

“I’m often rereading Borges when I might be reading something new.”

Not a bad epitaph.

Look, life is fleeting. Everything is not for everybody and it’s not necessary to have read everything any more than it’s necessary to have heard every piece of music. And it’s probably better to read one work deeply than skate along the surface of the new.

I don’t reread the classics so much as browse them. I’ll take out Homer, or the Anatomy of Melancholy, or the KJV and read a bit regularly. For street cred I will say I’ve actually read Melmoth the Wanderer and Don Quixote.

The contemporary authors I’ve discovered in the last ten years that I’ve enjoyed the most are Thomas Ligotti and the Icelandic Sigurjón Birgir Sigurðsson who writes as Sjón. (The Whispering Muses is amazing.)

Bravo John on finally reading Gravity’s Rainbow, something I never accomplished. My copy of the book is the 1974 Bantam Edition, pictured here on my Eye Candy for Bibliophiles blog.

http://eye-candy-for-bibliophiles.blogspot.com/2010/02/general-fiction-vladimir-nabokov.html

John: Ah, but then you miss the thrill of seeing a bookmark protruding from the three-quarter point of a fat volume.

Stephen: I’ve never felt concerned about missing various literary classics. I read some Dickens at school, for example, but don’t feel a great urge to read him now even though I’ve read a fair amount of Victorian fiction. I’m always urging people to read Robert Louis Stevenson, however. And hats off to Mr Ligotti. I was going to write “thumbs up” but “thumbs down” might be more appropriate given his general philosophical outlook.

Anne: That Bantam edition is one of the best designs among the paperbacks. Designers and publishers are curiously lazy with Gravity’s Rainbow, lots of outlines or diagrams of V-2 rockets but little else. Would-be readers could be forgiven for thinking it was a very serious historical drama. I think you might enjoy Vineland; shorter, lighter, very funny, and with none of the eccentricities of the Rocket book. All about people who were young in California in the late 1960s trying to cope with life in the 1980s.

read gaddis the recognitions and your pynchon balloon of him as some creative genius will immediately deflate,

read some reviews of the recognitions ( a number of years before pynchhitting was published) and maybe you’ll get what was going on.

Have mercy, but I love the book. Took seven weeks while unemployed to knock it off and being a young, ignorant whelp, I’m sure I missed a lot, that a lot flew right over my head.

But my favorite part or aspect of it was the underlying history which, you know, doesn’t quite comport the official US history of WWII — a/k/a The Big One — which, you know, is predominantly a fiction, more so when it comes to the European theater. Mind blowing AF, it was. Being on the spectrum (maybe even further along than I realize), I have to be in autodidact mode 24/7/365 so, you know, I learn from as much as possible as frequently as possible. And Gravity’s Rainbow was like an ur-history text for me, teaching that the official story may not be the correct story.

And to circle back to official histories and stuff, the amount of whitewashing and fantasizing that goes into at least the American version of the war in Europe is mind-blowing and still essentially hidden. Of course, grunts, on return from war, did what people are hardwired to do: Not discuss it and try to forget as much of it as possible. And the establishment, as it were, and ruling class were cool with that.

And then, as I said, I read Gravity’s Rainbow…

Damn straight it should be highly recommended.