…one ought to be able to hold in one’s head simultaneously the two facts that Dalí is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being.

George Orwell

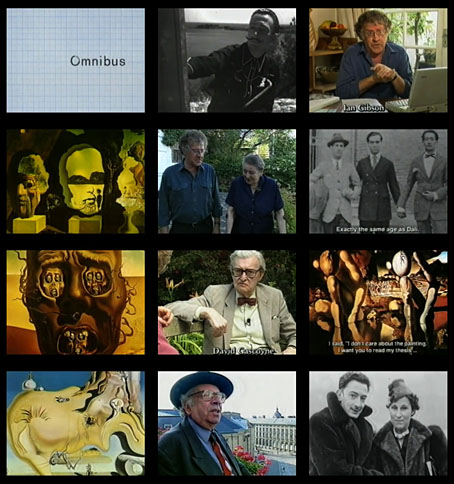

This two-part, two-hour TV documentary from 1997 has a title that makes it sound like more of an exercise in audience pandering than was typical for the BBC’s Omnibus arts strand, fame and shame being qualities that might be considered of greater interest for the general viewer than art history. But Michael Dibb’s film is more insightful than those made 20 years earlier when access to the Dalí circle, and to Dalí himself, required flattery and capitulation to the artist’s whims and attention-grabbing antics. In place of the impersonal approach taken by the BBC’s Arena documentary from 1986 we have writer Ian Gibson serving as a guide to Dalí’s life while conducting research into a major biography, La vida desaforada de Salvador Dalí (The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí), which was published a year later. “Shame” here refers more to Dalí’s numerous fears and phobias, especially those of the sexual variety, rather than to scandal and public opprobrium, while “Shameful Life” echoes the “Secret Life” title of the artist’s autobiography. Dalí’s sexual neuroses were always to the fore in his art but they remained concealed in his personal life, although the evasions—his frequent declarations of impotence, for example—don’t prevent Gibson from speculating. I saw this documentary when it was first broadcast but had forgotten the discussions of a possible homosexual relationship with Dalí’s adoring friend, Federico García Lorca, as well as the mention of the artist’s voyeurism, all of which was explored in more detail (and with some personal experience) by Brian Sewell a decade later in the TV documentary with the most prurient title of them all, Dirty Dalí: A Private View.

Gibson is a guide with the advantage of being a fluent Spanish speaker able to engage in conversation with those who knew or worked for the artist. Several of the interviewees are familiar faces in Dalí films: Amanda Lear, art collectors Reynolds and Ellen Morse, Dalí’s first secretary and business manager, Captain Peter Moore, and painter Antoni Pitxot. 1997 was about the last time it was possible to make a documentary about Dalí that might feature interviews with people who knew the artist in his younger days, although José “Pépin” Bello, born the same year as Dalí in 1904, lived on until 2008. Bello was the sole surviving member of a Madrid student group in the 1920s whose other members were Dalí, Luis Buñuel and Federico García Lorca. He also turns up in The Life and Times of Don Luis Buñuel (1984), another BBC film which really ought to be on YouTube, where he makes unsubstantiated claims about having contributed ideas to Un Chien Andalou. It’s easy to be sceptical about the assertions of an uncreative man whose youth had been spent in the company of three great talents but according to this obituary both Dalí and Buñuel confirmed the claims. (The image of a rotting donkey, however, had appeared in Dalí’s paintings before the film was made.)

Among the other people talking to Gibson are Surrealist poet David Gascoyne, and also George Melly, a man who for a long time was a ubiquitous presence whenever Surrealism was being discussed on British TV. The interviews are separated by clips from other films, two of which have featured in earlier posts: Hello Dalí! (which I keep hoping someone will upload to YouTube in better quality), and Jack Bond’s film of Dalí in New York in 1965. I watched both these again last year when I followed my viewing of the Svankmajer oeuvre with a number of Surrealist documentaries. Jack Bond’s film is especially good for its verité qualities, and for Jane Arden’s attempts to persuade Dalí to talk seriously for once about his art.

• The Fame and Shame of Salvador Dalí: Part One | Part Two

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Figures of Mortality: Lawrence versus Dalí

• Être Dieu: Dalí versus Wakhévitch

• Chance encounters on the dissecting table

• Salvador Dalí’s Maze

• Dalí in New York

• Dalí’s discography

• Soft Self-Portrait of Salvador Dalí

• Mongolian impressions

• Hello Dalí!

• Dirty Dalí

• Impressions de la Haute Mongolie revisited

For my entire life Dali has been a cultural icon and reproductions of his work in various media ubiquitous. So John a request for an artistic opinion from you if you please.

Is Dali really any good?

I’ve always believed he was very good indeed but, as with Picasso, his fame and notoriety tend to overwhelm appraisal of his painting. It’s odd that many of the things people used to criticise Dalí for (and still do on occasion)–being obsessed with money, endless self-promotion, and so on–don’t get levelled in the same way towards today’s crop of celebrities. So in that respect he was ahead of his time, something I think Andy Warhol acknowledged. The art world today is more obsessed with money than Dalí ever was.

Where painting is concerned, Dalí combined an exceptional technical mastery with the ability to find visual rhymes in the most unlikely and surprising places. My favourite example of this is The Metamorphosis of Narcissus which contains in a single image the male figure gazing at his reflection and a hand holding a egg from which a narcissus emerges. But the visual tricks are only a small part of his work. In his early paintings he may have borrowed some motifs from de Chirico (something I noted in a post last year) but he also defined a pictorial space that’s as immediately recognisable as the imagery of Magritte: the limitless plane, the obsessive repetition of certain figures and objects, the hard shadows of a Mediterranean sunset, etc. He also continued to keep moving his work forward, something that critics who dismiss everything he produced after he went to the USA seldom mention. He was the probably first painter to incorporate the imagery of nuclear physics and other scientific developments such as the discovery of DNA into his work, something he was doing in the 1950s when the main American trend was for abstraction, an idiom which can’t address these kinds of issues. JG Ballard wrote some good pieces about Dalí which don’t ignore his later paintings. They’re worth seeking out.