Another week, another obscure black-and-white science fiction film. I hadn’t heard of this one at all until it was announced in 2012 that co-director Tom Huckabee would be attending a rare screening in New York. The film is an oddity with a complicated history that I’m too lazy to try and condense so here’s the borrowed detail:

IMDB: In a dystopian future, Europe is unified under a totalitarian patriarchy, where each town is assigned a single economic purpose. In Brendovery, Wales the occupation is prostitution. Arriving by train from London is Billy Hampton, a young American expatriate and draft evader (Bill Paxton in his first lead role), ostensibly there to enjoy a sex-filled holiday. Unknown to him he is a time bomb assassin, programmed by a feminist terrorist cell to assassinate the local minister of prostitution.

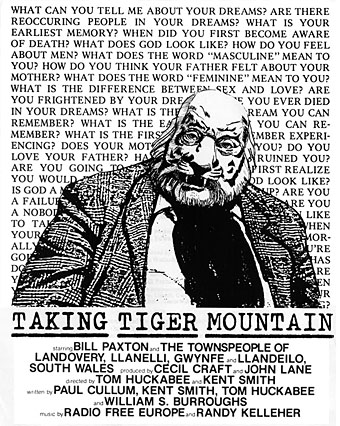

Wikipedia: Taking Tiger Mountain is a 1983 American science fiction film directed by Tom Huckabee and Kent Smith, and starring Bill Paxton in one of his earliest on-screen acting roles. Originally conceived as an experimental art film inspired by a novel by Albert Camus’s 1942 novel The Stranger and a poem by Smith, the film was initially directed by Smith and shot in Wales. Aside from Paxton, the film’s cast is made up of townspeople from the areas in which shooting took place. It was filmed without sound, with the intention of adding dialogue in post-production. During post-production, Huckabee took over as the film’s director, abandoning Smith’s original concept and instead loosely basing the film on the 1979 novella Blade Runner (a movie) by William S. Burroughs. The film premiered on March 24, 1983. Over three decades later, Huckabee re-edited the film and released it as an alternate cut titled Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited.

Tom Huckabee: The story went through four distinct periods of creation:

1. Kent Smith’s original script, entitled Taking Tiger Mountain, written in 1974, based loosely on the John Paul Getty III’s kidnapping of 1973 and Albert Camus’ The Stranger. It was set in the casbah of Tangier, Morocco.

2. After Bill and Kent got ejected from Morocco before shooting even a foot of film, they drove to Wales, adapting the script significantly to the new location and the people and opportunities that presented themselves; but they ran out of film and money after shooting about half of their script.

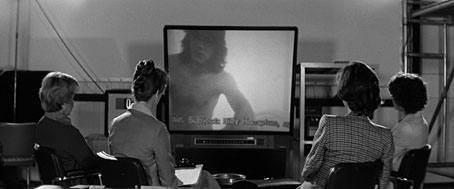

3. After I acquired the footage in 1979, I knew I couldn’t go back to Wales, so after editing their footage to about 55 minutes, I wrote a new story with a lot of help from collaborators, like Paul Cullum, Lorrie O’Shatz, and Ray Layton. I incorporated the Burroughs material and dropped the 55 minutes from Kent and Bill’s script into it. We wrote the ten-minute introductory section with the women and shot it on a sound stage in Austin, incorporating footage from another unfinished film by Kent and Bill called D’Artangan. I also built ten minutes of scenes from outtakes. In 1980, Paxton came to Austin for a few days to “loop” all of his dialogue, as no sound had been recorded in Wales. He improvised a lot of his voice-over narration, while under hypnosis. This film, called Taking Tiger Mountain, was released on 35mm in 1983 and toured the Landmark Theater chain of art cinemas.

4. In 2016 I got a small advance from Etiquette Pictures for digital distribution and decided to do a major upgrade. I cut out ten minutes and added five, including the new ending, which comes after the end credits, significantly changing the message of the film. I reworked the narrative, making it easier to follow.

In addition to the complications of the production it’s necessary to note that the title has nothing to do with either Brian Eno’s Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), or the Chinese opera the Eno album is named after, although we do get to hear about a tiger mountain. This reflects the equally tangled history of the “Blade Runner” title, which Taking Tiger Mountain does have some connection with via William Burroughs’ Blade Runner: A Movie. This was Burroughs’ cinematic reworking of a science fiction novel by Alan E. Nourse, The Bladerunner (1974), a piece of futurism about the very American dystopia of a nightmare healthcare system. Blade Runner: A Movie followed Burroughs’ earlier screenplay/novella, The Last Words of Dutch Schultz, although the Nourse adaptation was a much more ambitious scenario with little chance of ever being filmed. No studio in the 1970s (or today, for that matter…) would have put up the money for something that’s like a wilder version of Escape from New York with added gay sex and time travel, however attractive this may sound. As is well known by now, the treatment’s title was later purloined by another film that has little else in common with anything discussed here.

All of which means that Taking Tiger Mountain is exactly the kind of thing guaranteed to stoke my curiosity: a Burroughs-derived science-fiction film made on the cheap by Americans in south Wales, of all places. Why Wales? Because Bill Paxton had been there as a foreign exchange student. I’m not sure I would have been as interested without the disjunctive frisson of gloomy, rain-swept Wales in the mid-1970s colliding with William Burroughs. That said, the blu-ray release from Vinegar Syndrome has two things immediately in its favour: for a micro-budget production the film has excellent photography (the black-and-white stock was provided by leftovers from Bob Fosse’s Lenny); and there’s a surprising amount of unsimulated sex, something that isn’t such a big deal today but certainly was in 1974. The youthful Bill Paxton is gorgeous and exceptionally photogenic, so the film is a pleasure to watch even when little of substance is happening.

The narrative of Taking Tiger Mountain is as vague as can be, unsurprisingly given the circumstances of the production, so it’s best to abandon expectations of being told a coherent story and regard the whole thing as a curious mood piece. Huckabee establishes the science fiction frame with a prologue sequence showing the feminist scientists discussing the brainwashing of Billy Hampton (Paxton), a process that involves, among other things, forcing him to question his heterosexual nature. Once Billy has been programmed with his assassin’s mission we see him on a train to the rural town of Brendovery where the SF scenario is maintained by continual public radio broadcasts describing the power struggles raging across the world. One of the few plot threads is delivered via the radio, the progress and eventual death of another assassin who passed through the brainwashing programme before Billy. Burroughs’ presence is felt most in these broadcasts especially the satirical touches, such as the description of Mormons and the Mafia joining forces in a USA at war with itself to defend Utah against the depredations of rival states. Equally Burroughsian is Billy’s encounters with two of the town’s teenage boys, one of them a thuggish type who enjoys playing with a knife, the other a gay boy who Billy possibly has sex with. Billy’s programming has left him confused and dissociated so we aren’t always sure that what we see on the screen is a real event, a memory or an hallucination. This quality and the frequently elliptical editing helps compensate for the film’s shortcomings, the most significant of which are the erratic post-production dialogue. Re-recording dialogue is a common procedure in film-making—all Italian films used to be shot without any on-set sound recording—but there’s usually the time and money available to make the post-production sound match the visuals. In Taking Tiger Mountain the minimal dialogue and visuals aren’t always well-matched or properly synchronised although this too can be regarded as a parallel to Burroughs’ theorising about the malleability of recordings. In The Electronic Revolution and in some of his novels Burroughs suggests a number of ways that sounds and visual images might be weaponised by scrambling and repurposing. Taking Tiger Mountain is a fascinating demonstration of the way in which pre-existing visuals can change their meaning by simple recontextualisation.

Where the science fiction is concerned, the Burroughsian atmosphere of Taking Tiger Mountain, together with its fragmented editing and mundane British setting places it closer to the New Wave of Science Fiction than most Hollywood fare, especially the work produced by the writers published in Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds magazine. New Wave SF cinema, if it exists at all, has always been very small category; offhand I can think of the two films that JG Ballard always championed: La Jetée and Alphaville; he also liked Godard’s Weekend and Last Year at Marienbad. After these you’d have to look to two films derived from New Worlds-published fiction, The Final Programme and A Boy and His Dog, both of which were low-budget adaptations that deviated from their source material. Taking Tiger Mountain feels closer to the spirit of New Worlds than this pair, especially its presentation of sex. The sexual content of New Worlds caused continual upset, as did the sexual nature of the New Wave in general compared to the often chaste and prudish space operas that preceded it.

The Vinegar Syndrome release contains the original 1983 print of the film together with Tom Huckabee’s Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited, a further recontextualisation that adds digital effects to many of the shots, often with little purpose. I’d advise staying with the original. Vinegar Syndrome has distinguished itself recently with blu-ray releases of two other works of offbeat science fiction from the 1980s: Slava Tsukerman’s Liquid Sky, and Klaus Maeck’s Decoder. The latter is heavily indebted to William Burroughs’ The Electronic Revolution, and features a brief appearance by the man himself. If you’re as bored as I am by Hollywood’s bloated CGI-fests then the reissue labels are there to stimulate your interest and intellect.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The William Burroughs archive

Thanks John for reminding me of the film. I remember when the Vinegar Syndrome edition hit the review circuit, I was intrigued first and foremost by the title (the Eno album if nothing else), but my attention went elsewhere and I forgot to investigate further. I must delve in more with a view to picking up a copy – these grungy, low budget oddities are quite tantalizing, post-synced dialogue and all. A few years ago I was randomly leafing thru the Time Out Film Guide and stumbled upon a review of a no-budget b/w US film from 1983 called King Blank which the TO reviewer summed up by saying “Think instead of Glen or Glenda, Throbbing Gristle and Eraserhead” which sounds to me like manna from Heaven. Unfortunately, all attempts to unearth copy, even thru the usual underground channels have drawn…a blank.

The mention of Wales reminded me that Michael Mann shot, unlikely as it seems, the central location of The Keep in a quarry in Wales, although a more profound reflection of that type of forlorn landscape might be found in the early recordings of Lustmord. I remember reading an interview with Brian Williams in which he spoke about living near a big industrial installation in Northern Wales and the influence it had on his music – certainly his very early work which retained some percussive Industrial color conjures up a Zone-style landscape, and of course he later went on to record his own Stalker- inspired album…

I used to have a mental list of obscure titles I’d spotted in reviews, films I’d hope one day to discover. Jodorowsky’s films were discovered this way, along with a number of others that I’ve written about in the past. One of the great pleasures of the present moment is seeing these obscurities being carefully restored and made available to a wider audience.

The Keep is flawed but its been a cult film of mine for many years. One of my current hopes is that Michael Mann may deliver the director’s cut he promised years ago. A recent edition of The Wire magazine had a feature about Tangerine Dream that mentioned a forthcoming documentary about the making of the film. If it materialises then it may prompt a renewal of interest.

Yes, I think we’re talking about – A World War II Fairytale: The Making of Michael Mann’s The Keep. It seems like this has been in production for far too many years but after a period of dormancy, it looks like the film is in its final stages of production. I really enjoyed the Dune documentary so let’s hope this one will be as good. I’m not entirely sure The Keep is deserving of such lavish attention although I’ve enjoyed the film more and more in recent times. There’s an Australian DVD out now that seems the current best version of the film, much better than the laserdisc copy that’s been doing the rounds on Film4. The Tangerine Dream soundtrack is the strongest aspect of the film I think, and I do love that moment, 20-odd minutes into Logos when The Keep music kicks in. How strange is it that the score incorporates a radical re-haul of Mea Culpa from My Life In the Bush of Ghosts and the theme from The Snowman, but then again most aspects of The Keep are quite strange. The writer of that Wire piece was wise to catch those two outliers on the soundtrack but I had to question his line about William Friedkin making extensive use of TD’s music in Sorcerer – it’s been a while since I saw the film, but I seem to remember quite a spare use of TD’s music in the film. As for the TD’s soundtrack work, I’ve been listening to my Near Dark CD lately, and while this is very late-in-the-day Tangerine Dream for me, I’ve been enjoying it nonetheless, and Kathryn Bigelow makes good use of it in the film.

Yeah, I don’t think I really need to see anything about the making of The Keep, I’d rather have a blu disc of the film itself.

That Wire piece was rather poorly written compared to their usual fare. I’m very familiar with Sorcerer on screen and album, and it’s true that there’s very little TD music in the film. Regarding Near Dark, watching Bill Paxton in the above reminded me that I’ve not seen the Bigelow film for years. I always regard it as one third of Eric Red’s “killers on the road” trilogy, together with The Hitcher and Cohen and Tate. All three films concern young males being taken on nightmare road trips by maniacs.