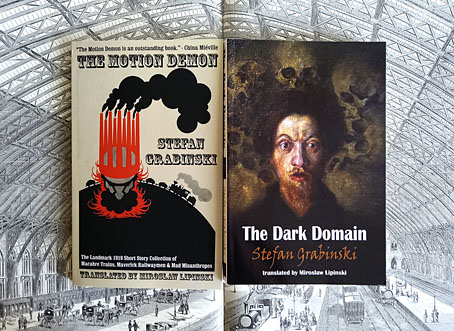

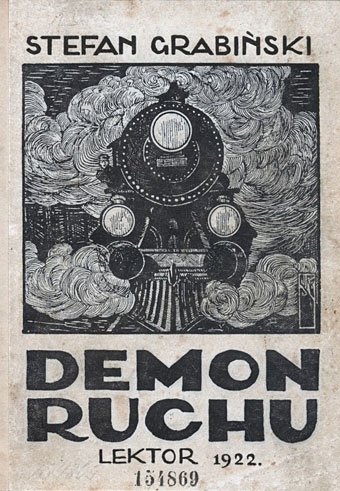

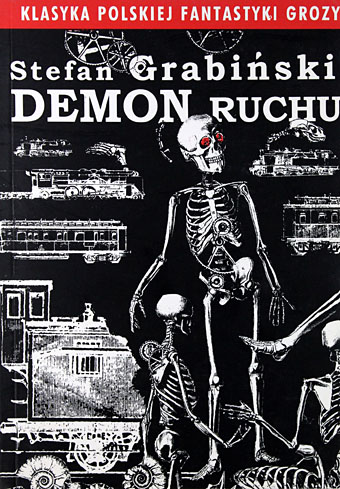

Thanks to the demons of distraction it’s taken me a long time to find my way to these books by Polish author Stefan Grabinski (1887–1936) but I’m very pleased to have done so at last. Grabinski was one of several writers first drawn to my attention by Franz Rottensteiner’s The Fantasy Book: The Ghostly, the Gothic, the Magical, the Unreal (1978), a lavishly illustrated popular study that charted the history of fantasy and horror fiction. The book is inevitably dominated by Anglophone authors but Rottensteiner was looking at the genres from a global perspective, to an extent that some of the writers in the sections devoted to Continental Europe were either difficult to find or, as with Grabinski, hadn’t yet been translated into English. Robert Hadji’s Grabinski entry in the Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (1986) further stoked my curiosity. Neither Rottensteiner nor Hadji mention how they came to read these obscure tales but I’d guess it was in the two collections published in Germany under the Bibliothek des Hauses Usher imprint, Das Abstellgleis (1971) and Dunst und andere unheimliche Geschichten (1974); several covers from the imprint appear in Rottensteiner’s book. Wherever it was that they read the stories, both writers praised Grabinski as an overlooked master of weird fiction. Rottensteiner notes that he was a contemporary of HP Lovecraft, and with a similar biography—briefly married and suffering artistic neglect during his lifetime—but neither Rottensteiner nor Hadji use the common shorthand descriptions of Grabinski as “the Polish Poe” or “the Polish Lovecraft”. These labels are intriguing but misapplied.

Bearing in mind that these stories are translated works, one of the surprises of finally reading them is how fresh they seem compared to so many British ghost stories from the same period. Grabinski was writing during the birth of Modernism but the stories of his Anglophone contemporaries can often read like the products of an earlier epoch. His economical prose lacks the ornamentation of Poe and Lovecraft, just as it lacks Poe’s morbid Romanticism and has nothing of Lovecraft’s cosmic scale. But there are recurrent themes, particularly that of possession, whether by the spirits of the dead, by inhuman elementals, or by idée fixe. The latter provides the subject of The Glance, a story that also demonstrates Grabinski’s knack of finding horror in the most mundane situations: a man whose wife died prematurely is troubled by the sight of an open door, the same door through which she walked out of his life, and subsequently, out of her own. The man’s obsession with the door grows into a fear of closed doors and the implicit tragedies they may conceal, an obsession that soon extends itself to anything that hides too much of the world: curtains, rugs, the sharp corners of city streets… Edgar Allan Poe was fond of cataloguing madness in this manner but Grabinski’s stories go beyond glib formulations of insanity. “Metaphysical” is a word often used in discussion of the Grabinski oeuvre; the fixations of his protagonists reveal truths about the world to which others are blind.

The other great Grabinski theme is trains and railways, a subject he returned to often enough to fill an entire volume with haunted locomotives and doomed rail employees. I respond on a visceral level to the suggestion that trains are engines of menace, I’ve always found them to be fearsome things despite their familiarity. Their size, their weight, the terrible momentum of a speeding train; the diesel trains that replaced steam engines in the 1960s could be as loud and filthy and mephitically noxious as their coal-powered ancestors. The train had increasingly dominated European life in the 19th century but few writers looked to railways or the industrial world for sources of horror. (HG Wells is a notable exception.) Trains for MR James are merely a conveyance for delivering his antiquarians to the next guest house or ecclesiastical ruin; in Grabinski the trains themselves are often the locus of horror. In this he pre-empts Fritz Leiber who found in modern cities a source of new spectres for a new century. Leiber’s Smoke Ghost is Grabinski avant la lettre, while Leiber’s recurrent theme of malefic inhuman forces is prefigured by Grabinski in stories such as The Sloven—a train conductor is convinced that rail disasters are prefigured by the appearance in the train of a shambling, spectral figure—and Vengeance of the Elementals, in which a city’s fire chief finds himself in conflict with the animated spirits of fire itself. In The White Wyrak, the soot that grows in chimneys is a breeding ground for something monstrous:

“Soot is dangerous, particularly when it accumulates in narrow, dark spaces unreachable by the rays of the sun. And not just because it can easily catch fire. No, not just because of that. Consider this, we chimney sweeps battle our entire lives with soot, we prevent its excessive accumulation, and so prevent an explosion. But soot is treacherous, my boy, soot lays dormant inside dark smoke chambers and stuffy furnances, and it lies in wait–for an opportunity. Something vindictive resides in soot, something evil lurks there. You never know what will emerge from it, or when.”

Lastly, there’s an overt eroticism in several of these stories which again is surprising when compared to their Anglophone contemporaries. Eros isn’t entirely absent from supernatural tales of this period but the allusions that outraged a 19th-century readership—the suggestions in Arthur Machen’s The Great God Pan, for example—are often so vague to 21st-century eyes as to be almost invisible. Grabinski isn’t vague, and he also isn’t unique in his lack of ambiguity, his stories merely demonstrate the gulf between European attitudes towards sex and the Anglophone prudery that would dilute or remove altogether the erotic content of translated fiction. Another of the train stories, In the Compartment, has the rail system itself as a generator of erotic frenzy, when a timid man is transformed by his obsession with the speed and energy of trains into a lustful extrovert.

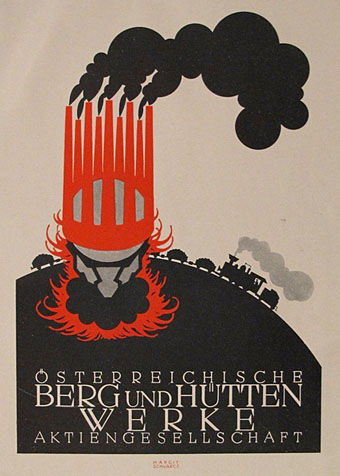

Berg und Hüttenwerke (1923), a poster by Margit Schwarcz. Only connected to Grabinski by its appearance on the Motion Demon cover but it’s a great design.

All the stories in these books have been translated by Miroslaw Lipinski who also maintains the Stefan Grabinski website. Even though Grabinski’s profile has risen in recent years there are still many of his stories awaiting translation into English. If Penguin were looking for another writer of weird fiction to follow their collections of Lovecraft, Machen and Clark Ashton Smith then Grabinski would be an ideal choice. His stories are sufficiently cerebral and finessed to satisfy readers demanding literary quality but they also satisfy those in search of an uncanny embrace. These trains shouldn’t be missed.

Further reading:

• Stefan Grabinski at Culture.pl.

• 7 Master Short Stories by Stefan Grabinski chosen by Mikolaj Glinski.

• Timothy Jarvis profiles Grabinski for Weird Fiction Review where he also finds a precursor to Fritz Leiber.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Bibliothek des Hauses Usher