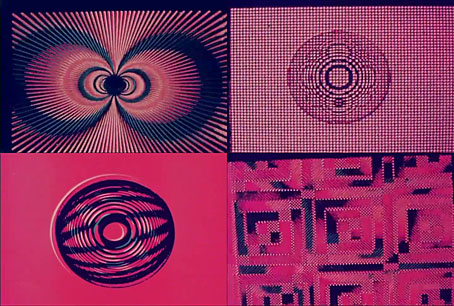

Further proof that if you wait long enough (almost) everything turns up eventually. In 2011 I mentioned a fruitless search for Moirage (1970), a short film by Stan VanDerBeek, and here it is, in a rather scratched print at the Internet Archive. The film proves to be as I expected, an abstract work that animates the kinds of patterns that would have been deemed Op Art in the few years before LSD use became widespread, but which were unavoidably psychedelic by the time VanDerBeek came to make his film.

The patterns were provided by Gerald Oster, a biophysicist who used his discoveries in photochemical research to create works of art. My Studio Vista guide to Op Art lists two Oster studies in its bibliography: a book, The Science of Moiré Patterns (1959), which included sheets of overlays for the reader to play with; and an article co-written with Yasunori Nishijima, Moiré Patterns, for Scientific American (May, 1963). (The magazine also had a moiré pattern as its cover illustration.) I was playing with moiré interference myself a few weeks ago so this discovery is a timely one. My experiments involved vector graphics, a much more versatile medium for creating these effects than the printed sheets that Oster and his colleagues had to create. I’d been thinking of using the patterns as part of a book design but haven’t decided yet whether they’re suitable.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The abstract cinema archive

John perhaps this is the appropriate time to ask a question I’ve had for years. Do you know how Jorden Belson achieved the effects he did in his later pieces? I’m thinking of the flowing water and cloudlike effects in his videos. Were these pre-existing films that were treated in some way or effects achieved by some technical process?

Articles about his work hardly delve into this aspect.

Thanks

Hi Stephen. That’s a good question, and it turns out that Gene Youngblood has a partial answer in Expanded Cinema which contains a whole chapter about Belson’s films:

“Belson’s work might be described as kinetic painting were it not for the incredible fact that the images exist in front of his camera, often in real time, and thus are not animations. Live photography of actual material is accomplished on a special optical bench in Belson’s studio in San Francisco’s North Beach. It is essentially a plywood frame around an old X-ray stand with rotating tables, variable speed motors, and variable intensity lights. In comparison to Trumbull’s slitscan machine or the Whitneys’ mechanical analogue computer it’s an amazingly simple device. Belson does not divulge his methods, not out of some jealous concern for trade secrets—the techniques are known to many specialists in optics—but more as a magician maintaining the illusion of his magic. He has destroyed hundreds of feet of otherwise good film because he felt the technique was too evident. It is Belson’s ultrasensitive interpretation of this technology that creates the art.”

You can download a PDF of the book here:

http://www.ubu.com/historical/youngblood/index.html

It’s been circulating in this form for many years so copyright doesn’t seem to be an issue. Essential reading on the subject of abstract/non-narrative cinema.

Terrific, thanks!

I’ve been a fan of Belson’s work since I saw the original Visual Music installation that included EPILOGUE at the Smithsonian Hirshhorn Museum here in Washington DC back in 2005. I’ve always imagined Belson doing the visual effects for some imaginary version of SOLARIS.

It’s surprising he wasn’t asked to do more work in feature films. Offhand I can think of brief sequences in The Right Stuff, and the same in Demon Seed. Something cosmic and philosophical like Solaris would have been ideal.