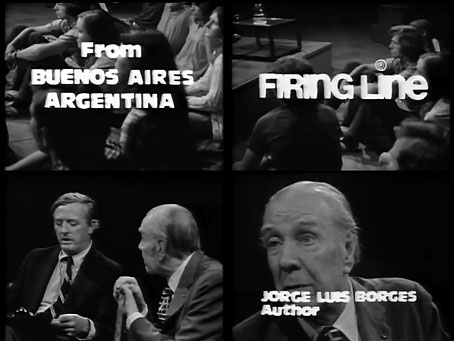

Jorge Luis Borges was interviewed on TV a number of times in later life but most of the available appearances are in un-subtitled Spanish. His 1977 meeting with William F Buckley on Buckley’s long-running debate and discussion show, Firing Line, is an exception, and a welcome one for being almost a whole hour of serious discussion. Buckley’s reputation has been reappraised in recent years. Gore Vidal famously accused him on live TV of being a “crypto-Nazi”, a barb that prompted Buckley to momentarily lose his usual composure. With American politics currently beset by actual Nazis, crypto- or otherwise, as well as people who wouldn’t crack open the spine of a book even if you offered them another tax break, Buckley now looks like an impossible figure: an American conservative who was also a genuine intellectual with a passion for literature.

The discussion on this occasion is less about Borges’ works than about language and literature. If you’ve read any Borges interviews then this is familiar territory, but Borges elaborates here on subjects that were only touched on elsewhere, especially the strengths of English over Spanish as a literary language, and the pros and cons of translation. This latter subject is a sore point for Borges readers such as myself who believe that the current translations (made after Borges’ death) are inferior to the earlier ones, many of which were prepared with the approval of the author. It’s painful to hear him say he thought his stories worked better in English, and it makes me wonder again what he might make of the present state of affairs.

Elsewhere, Buckley tries to lead Borges into a discussion of politics, a subject that he generally avoided because it didn’t interest him, and whenever he did mention the subject he’d usually get into trouble by saying something that would annoy one side of the political spectrum or the other. I was pleased to note a fleeting reference to Arthur Machen, mentioned in relation to the Julio Cortázar short story, Casa Tomada (House Taken Over), which Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares and Silvina Ocampo reprinted in their Antología de la Literatura Fantástica (1977).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• La Bibliothèque de Babel

• Borges and the cats

• Invasion, a film by Hugo Santiago

• Spiderweb, a film by Paul Miller

• The Library of Babel by Érik Desmazières

• Books Borges never wrote

• Borges and I

• Borges documentary

• Borges in Performance

I like a post that name checks Borges, Ocampo, Cortázar AND

Buckley AND Machen

Speaking of languages, translation and being in the firing line: when Manchester’s very own Anthony Burgess met Borges at a party in Argentina, they recited alternate lines of Anglo-Saxon poetry to each other, thereby baffling the secret policemen who were hovering to listen for subversion.

This was under the fascist regime in Argentina, of course. I didn’t think when I first read the story in Burgess’s autobiography that there would be fascist regimes much closer at hand than Argentina. Incipient ones, at least.

“…the strengths of English over Spanish as a literary language…”

Which raises the question of which is exactly the best literary language. Perhaps Joyce answered that by refusing to be limited to any language in particular. But even Joyce didn’t use much Japanese and Chinese, whose writing systems give them qualities and subtleties unknown to readers of merely alphabetic scripts like Spanish and English.

I remember Burgess relating that anecdote on a talk show. He also said they chatted about the related origins of their surnames.

I think Japanese might well be a good candidate for best language given the antiquity of The Tale of Genji.

“I remember Burgess relating that anecdote on a talk show. He also said they chatted about the related origins of their surnames.”

Yes — also related to bourgeois. One of my favourite things about AB is his logomania.

“I think Japanese might well be a good candidate for best language given the antiquity of The Tale of Genji.”

Agreed, but it’s nowt compared to the antiquity of the Epic of Gilgamesh! What may also make Japanese best is that it has the most complex script of all, because (inter alia) it mixes Chinese logograms with a quasi-alphabetic system. So it’s a kind of Chinese-with-knobs-on. And calligraphy in Chinese and Japanese is a much more serious art than it is in languages like English or even Arabic. You aren’t so much writing as painting or conjuring logo-demons.

If Joyce had been Japanese, he would have been a literary mega-nova, man.