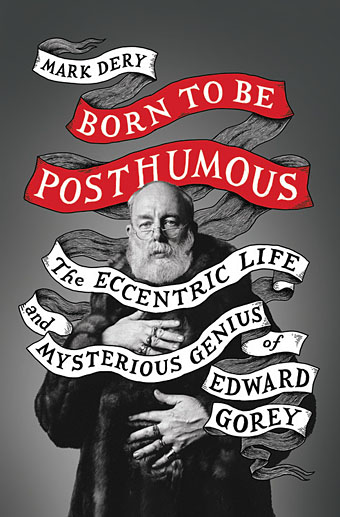

Cover design by Jim Tierney; photo by Richard Corman.

When so many current biographies are recounting the lives of those about whom we’ve already heard a great deal (see the new biography of Oscar Wilde by Matthew Sturgis), a book exploring the career of a previously undocumented yet worthwhile figure is especially welcome. Such is the case with Born to Be Posthumous, Mark Dery’s life of the elusive Edward Gorey: artist, writer, illustrator, book designer, book creator, bibliophile, theatre designer, cat lover and balletomane.

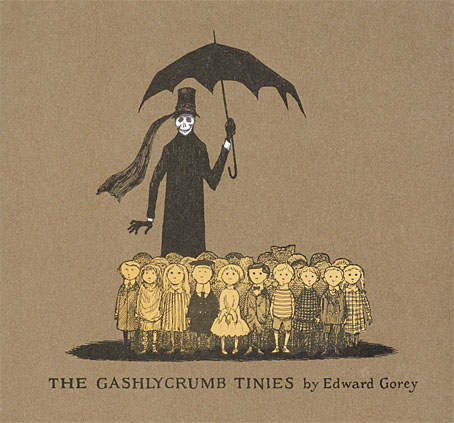

The Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963).

Gorey’s small books have long been one of the more curious fixtures of American culture: many of them look like children’s books but aren’t (unless the child is Wednesday Addams); others look like comic books but they aren’t comics either. The books are sometimes (but not always) Surrealist fables; or brief accounts of irreducible mystery; or sombre inexplicabilities; or camp ripostes to the pieties of Victorian morality; infrequently spiced with black humour and with lurches into outright horror. Gorey delivered his miniature tales in an idiosyncratic drawing style that combines a cartoon-like stylisation with the density of shading found in old wood engravings, a blend that would prove influential as his popularity grew. As Dery notes in his book’s introduction, without Edward Gorey’s work there would be no Lemony Snicket, while Tim Burton would be a skeletal shadow of his present self. (Given the latter’s current output, this might do him some good. But I digress.)

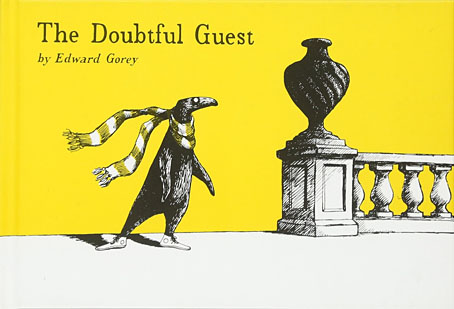

The Doubtful Guest (1957).

In Britain, however, Gorey remains a cult rather than cultural figure, still overshadowed by better-known contemporaries such as Maurice Sendak and Charles Addams. Until the publication of the Amphigorey story collections Gorey’s books were produced in small editions with such a limited availability you were more likely to encounter his art on the cover of another author’s book than within the pages of his own. I became aware of Gorey’s work by gradual osmosis. The first substantial piece I read about him was his entry in Philip Core’s Camp: The Lie that Tells the Truth (1984), in which Core’s mention of an art style “recollecting Victorian engravings” marked Gorey as an artist to be investigated. Two years later he received a longer entry in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural edited by Jack Sullivan. (Camp and horror: how many other artists sit so easily in both worlds?) But Gorey is absent from many books about 20th-century illustrators, and despite the sequential nature of his work you won’t find him in histories of comic art.

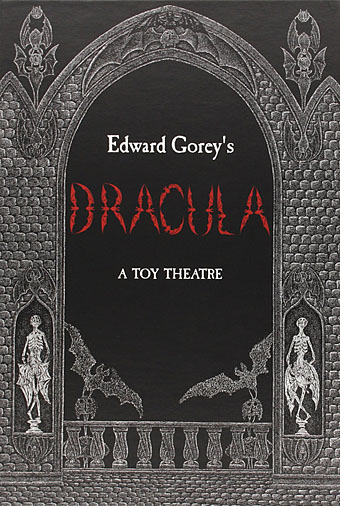

Edward Gorey’s Dracula: A Toy Theatre (1979).

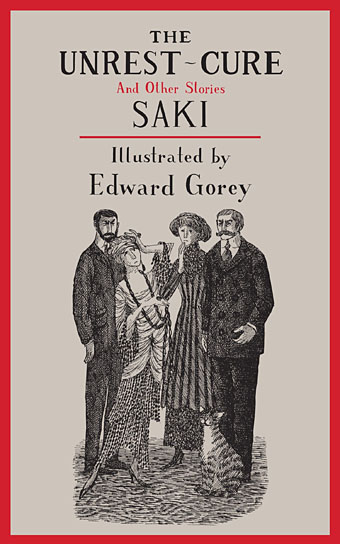

In a way it’s fitting that the work of a man who was adamant in his determination to avoid being pinned down should be so difficult to find. But it’s also a shame that the work of an ardent Anglophile should be hard to find in the country that fuelled his imagination. Among Gorey’s literary favourites Dery lists Jane Austen and Agatha Christie together with Ronald Firbank, Saki, and EF Benson’s Mapp and Lucia novels. (The latter trio are all present in Core’s book on camp, which no doubt makes Gorey camp to the core. Whether he would have approved of being labelled as such is another matter.) I wasn’t surprised by the mention of Saki when so many of Saki’s story titles (The Secret Sin of Septimus Brope) sound like Gorey books, while many of the stories themselves are like Gorey scenarios in prose. Not all Gorey’s work is camp or comic, however; the 32 drawings that comprise the wordless masterpiece of The West Wing (1963) are closer to David Lynch or the “strange stories” of Robert Aickman, the latter an author that Gorey illustrated on several occasions. Dery emphasises how Gorey’s love of silent cinema contributed to The West Wing and other pieces, especially the serials of the Surrealists’ favourite filmmaker, Louis Feuillade.

There’s so much in this life and work with which I fully identify that the experience of reading Dery’s book is to feel increasingly slighted and deprived that I wasn’t allowed access to all the available Goreys at a much younger age. To take the example of engraved illustrations: Gorey is the first person I’ve encountered who articulates the weirdness I’ve always found attractive about old engravings, a quality the creators never intended but which grows more pronounced with the passing of time. Max Ernst harnessed some of this in his engraving collages but Ernst’s works are less about the peculiarity of the uncollaged pictures than the potential they provide for attacking the values of his parents’ generation. Gorey’s drawings tease out the uneasy implications of a dead world revealed through stilted illustrations and advertising art, distilling and refashioning the weirdness with his pen and ink.

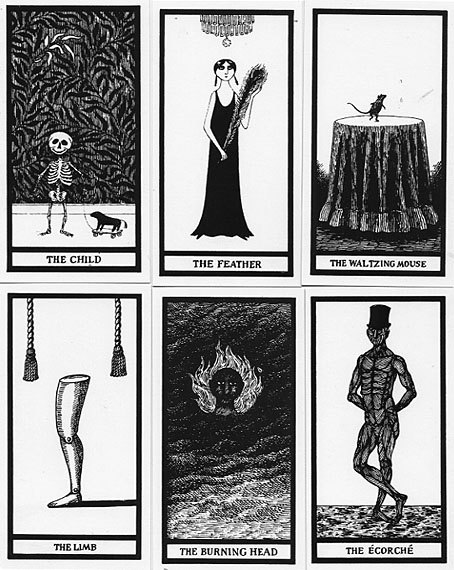

The Fantod Pack (1995): a Gorey take on the Tarot deck.

Born to Be Posthumous is a detailed and insightful book, charting Gorey’s progress from aimless student, to jobbing designer and illustrator, to enigmatic cult figure, to equally enigmatic institution. Gorey’s cheerful disregard for boundaries can been seen in his favourite streetwear—rings and fur coats combined with jeans and sneakers—and Dery is at ease whatever boundaries those sneaker-clad feet happen to traverse: literary, artistic, theatrical, or shuffling uncomfortably at the margins of popular culture and a burgeoning world of gay liberation. Not all the enigmas are resolved but when Gorey so much relished a lack of resolution in his work and his favourite art it’s no surprise if his life resists any simple quantification. I was a little surprised there wasn’t more artwork in the book but the drawings or covers under discussion can be found online easily enough.

Born to Be Posthumous is published by HarperCollins, and will be available in Britain from the 19th of this month. Mark Dery generously agreed to answer a few of my questions about Gorey’s life and work.

* * *

JC: Edward Gorey’s art style is unusual for a 20th-century artist, with cartoon-like figures placed in densely cross-hatched settings. Did he ever acknowledge any particular influence on his drawings?

MD: He did, although some of his responses to interviewers’ proddings on that point were more rightly interests, not all of whom left their fingerprints on his work. For example, he admired Balthus and Bacon enormously—he once claimed they were among his three favorite painters, the other one being Magritte, a definitive ruling we’ll have to take with a grain of salt since Gorey’s “three favorite” anything seemed to change with every interview. That said, he was unequivocally a Bacon devotee; in the book, I quote him “swooning at the sheer beauty of the painting” after seeing a Bacon exhibition, so much so that he can imagine “being able to live with the triptych where something horrid has taken place in the middle panel; all that gore and even the zipper on the bag are superbly painted.” Can we detect Bacon’s influence on his work? I can’t, nor that of Balthus, which makes a point that always bears repeating, namely, that interests aren’t necessarily influences.

Gorey’s avowed influences were Tenniel, or more properly Tenniel’s engravers, the Dalziel brothers, who gave his Alice illustrations their characteristic sharply incised, squared-off look; Ernest Shepard’s drawings for the Winnie-the-Pooh books and Wind in the Willows; Gustave Doré, of course, though he only mentioned him passingly; Japanese printmakers from the Ukiyo-e period such as Hokusai, whose stylized waves show up in several Gorey books and whose eloquent use of white space as a kind of visual silence influenced Gorey greatly; Magritte, as noted earlier, whose signature marriage of flatly reportorial technique with dreamlike imagery echoes through the pages of Gorey books like The West Wing; and of course any number of anonymous Victorian illustrators of Gothic novels, penny dreadfuls, and shilling shockers. Max Ernst’s collage novels were a profound influence; gun to head, I’d say his greatest, since Ernst’s necromantic ability to conjure forth the surrealist uncanniness inherent in late 19th-century engravings lies at the heart of Gorey’s aesthetic.

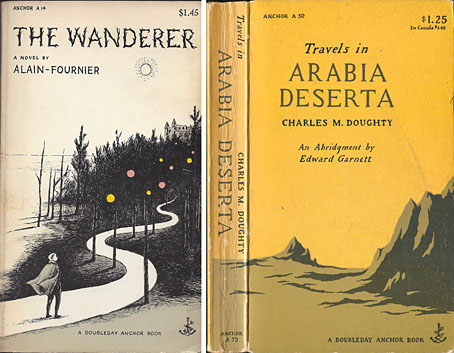

It should be noted, in any conversation about Gorey’s influences, that while he was first and foremost a draftsman (“Line drawing is where my talent lies,” he said in a 1978 interview) and is known largely for his black-and-white aesthetic, his color sense was pitch-perfect. It’s abundantly on display in his use of an odd, “off” palette and subtle watercolor washes in his cover art for Doubleday’s groundbreaking Anchor line of paperbacks, a landmark of innovative design in the first flush of the postwar paperback revolution. As it happens, his mastery of color owes much to the British jacket artists of the ‘40s and ‘50s whose work he loved, most obviously Edward Ardizzone and Edward Bawden.

Two of Gorey’s many covers for the Anchor imprint.

JC: The popularity of Gorey’s books has tended to overshadow his other career as a prolific cover designer and illustrator. He obviously cared a great deal for books in general—he had a huge personal library—so I wonder whether he regarded his work for Doubleday and other publishers as a worthwhile pursuit in itself, or simply a means of earning a living while he was creating books of his own.

MD: A perfect segue! He was yawningly dismissive of his work for Anchor, though one never knows if that was just part of his self-deprecating pose: Gorey, whose only formal training as an artist consisted of high-school art classes and a few courses in commercial art and cartooning at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, was secretly insecure about his talent and technique, as so many artists are. It’s a pity, since his Anchor covers, as I argue in the book, pushed the envelope of commercial design and played a seminal role in establishing the mass-market book cover as a canvas for trailblazing design and illustration. Yet despite Gorey’s pooh-poohing of his book-cover work, the design critic and historian Steven Heller managed, in his interview with Gorey (included in the interview collection Ascending Peculiarity), to draw him out on the subject with fascinating results.

JC: JG Ballard used to say that he learned everything about America by watching re-runs of The Rockford Files; his view was a mediated one, in other words. Gorey’s Anglophilia is evident from his first book, The Unstrung Harp, and his view of England is even more filtered than Ballard’s was, being a blend of his own imaginings with half-memories of scenes from old stories, films and so on. Gorey’s England is so fantastical I’m sure the reality would have disappointed him. Did he ever travel here?

MD: He did, although with predictably Goreyan perversity he passed through England, the setting for nearly every one of his little books, without traveling in it, in the sense that you mean. Enraptured by the Powell and Pressburger gothic romance, I Know Where I’m Going (1945), set in the beautiful desolation of the Hebrides, Gorey—who barely traveled outside Manhattan, let alone outside the States—took a tour in the summer of ’75 of the islands off Scotland’s west coast—the Outer Hebrides, the Orkneys, the Shetlands, Fair Isle —then hopped on a train to London and flew straight back to New York. As far as he know, he never set foot in England, beyond the occasional railway platform and Heathrow’s departure lounge. In the book, I quote his good friend the feminist literary critic and fellow Anglophile Alison Lurie: “England before, let us say, 1930 or ’40—that was the period that he liked, and he didn’t want to see the England of supermarkets and shopping carts—the Americanized, commercialized England that developed after World War II.” As with all Anglophiles, Gorey’s England couldn’t be found on any map, and he wanted to keep it that way. His England—the England of the darker Dickens, of Agatha Christie, of Conan Doyle, of Tenniel and Lear and Carroll, of Ronald Firbank and Ivy Compton-Burnett, of Wilde and Waugh’s Bright Young Things—would’ve vaporized on contact with the gray, collapsing welfare state of England in 1975, where Thatcher and the Sex Pistols waited in the wings.

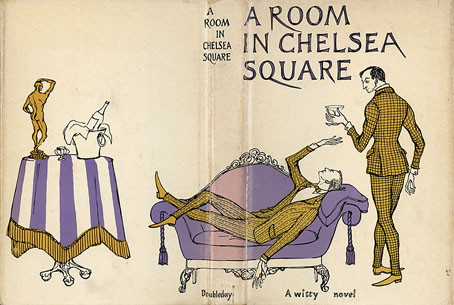

A Room in Chelsea Square (1959) by Michael Nelson. A gay novel with a Gorey cover whose early editions were published anonymously.

JC: One of the most popular features of this blog has been the gay artists archive which lists all the posts I’ve made about homoerotic art or gay artists from the ancient world to the present day. Gorey said he wasn’t sure he could categorise his sexuality so I wouldn’t want to try and pigeonhole him by placing him in such a list. (Some of his work can be read as camp but this isn’t always synonymous with being gay.) But biographies today seldom ignore a subject’s private life, especially if it was mysterious or unresolved. Did your researches yield any further information on the matter?

MD: I’m going to take the fifth on that one, on the grounds that anything I might say would constitute a spoiler. Readers interested in finding the smoking gun that solves the Curious Case of Edward Gorey’s Sexuality are advised to read the book.

JC: For a variety of reasons Gorey is still a cult figure in Britain. If I was recommending his work to new readers I’d suggest as a starting place one (or all) of the Amphigorey collections. Are there any of his books you’d suggest as good introductions for the curious? Or, if not, any favourites?

MD: The first of the four Amphigorey omnibus collections of his little books, Amphigorey, is typically the gateway drug to Goreyland but that format, with its low-res reproductions and altered layouts, really does do the silent-movie pacing and dizzy detail of his densely crosshatched works a disservice. Better to spring for one of Pomegranate press’s top-notch reprints of his books in order to experience them in all their “biscuit-y” deliciousness, as Gorey’s friend Alexander Theroux put it. I’d buy The Doubtful Guest as a kind of droll amuse-bouche, then dive into the “serious” works whose philosophical profundity, always lightly worn, and peerless illustrative technique reveal Gorey at the peak of his powers: The Object-Lesson, The Iron Tonic, The Willowdale Handcar, and The West Wing, a “silent” (textless) drift through a surrealist haunted house that manages to evoke Ernst’s collage novels, Magritte, and the mood of The Haunting of Hill House in a few pen-and-ink panels. Chase them with the perverse, and perversely funny, parody of Jazz Age pornography, The Curious Sofa; the queasy, deeply disturbing Loathsome Couple, based on the Moors Murders; and the absurdist nursery rhyme, The Nursery Frieze, and the painfully poignant valentine to one of Gorey’s hopeless, hapless romantic crushes, L’Heure Bleue, with its exquisite palette of black, white, and midnight blue. If you’re not hooked by that point, there’s no hope for you, I’m afraid. •

• Further reading: Goreyana: A blog celebrating the works of Edward Gorey

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Edward Gorey book covers

Thank you John for this post;

Thank you Mark for this book;

but esp.

Thank you Ogdred Weary for this

ETERNALLY…

TjZ, Food Preparer for THE INSECT GOD

. . . but no mention of the opening and closing credit sequences of PBSs Mystery, the images of which brought him into tens of millions of American households?

. . . but . . . I wonder if there was any UK exposure to such as that?

Hi Scott. I did link to the Gorey title sequence a couple of years ago:

http://www.johncoulthart.com/feuilleton/2016/02/28/weekend-links-298/

It was never shown here, however. The series repackaged many British TV productions for US audiences. Over here we got the individual episodes (Miss Marple and so on) in runs of the entire series. This is what I mean about Gorey’s visibility in the two countries: in the US he became very well-known whereas here he’s only known to aficionados since most of his outlets–book covers, magazine illos, etc–were limited to the US.

That’s sound like a delightful book. Gorey is a late discovery for me as well and I adore him.