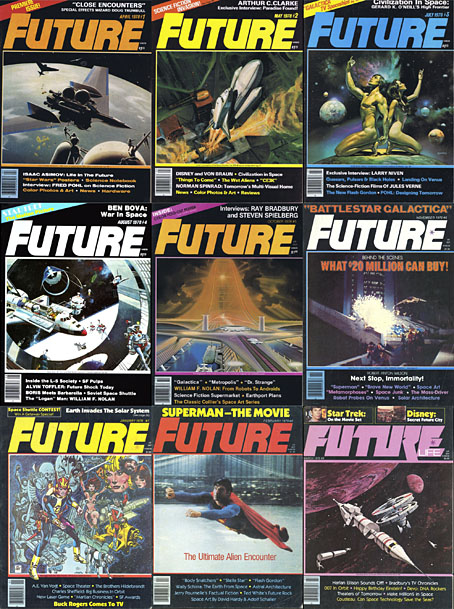

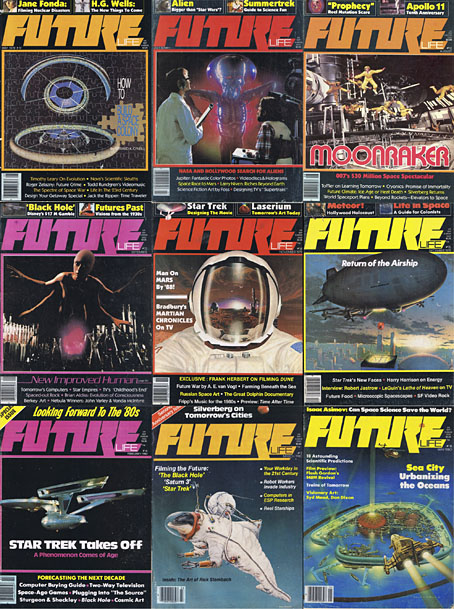

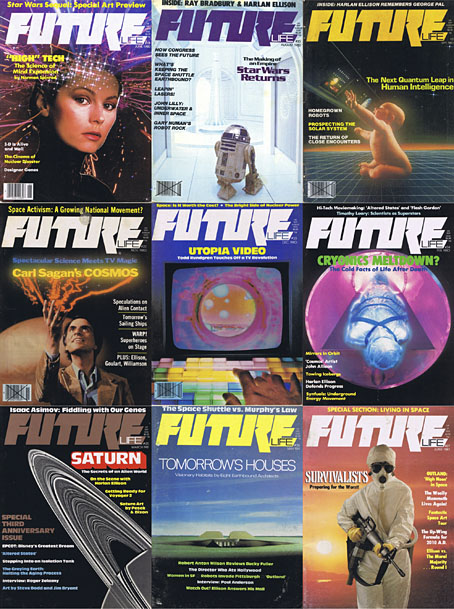

One thing I never expected about the future was that so many of my youthful enthusiasms would keep rising from the past, but here’s another, stumbling into the room reeking of cemetery earth and old newsprint. Future Life was a spinoff from Starlog magazine, and where the parent title concerned itself with science fiction and fantasy in film and television, the focus of Future Life was technology, popular science, scientific speculation, and written science fiction (all from an American perspective, of course); film and TV productions were there to attract general readers but never dominated the proceedings. Future Life ran for 31 issues from 1978 to 1981, and in many ways the magazine was a kind of OMNI-lite: not as lavish as its rival but not as expensive either. For a while this was a magazine I always looked out for (together with Heavy Metal, with whom it shared a music writer, Lou Stathis) but I missed the first nine issues, and many of the later ones before it vanished altogether, so it’s gratifying to find the complete run available as a job lot at the Internet Archive.

It’s become commonplace today to regard Generation X as the first generation with no optimistic future to look forward to, but Future Life shows how much optimism there was at the beginning of the 1980s. The mood darkened just as the magazine expired, with genuine fears of a nuclear war persisting through much of the decade, and the Challenger disaster reminding everyone that leaving the planet was still a hazardous business. Future Life wasn’t blind to the problems posed by technology—there were features about the dangers posed by nuclear power and climate change—but it remained upbeat about the potentials, especially where space colonies were concerned. Most issues carried an art feature although these were generally about realistic space artists or spaceship painters, with none of the eye-popping weirdness favoured by OMNI. But this magazine was my first introduction to the work of Syd Mead, a few years before Blade Runner made him deservedly famous. On the writing side, many of the articles were by popular science fiction writers—Roger Zelazny on computer crime, Norman Spinrad on a pet theme, the future of drug-taking—which you can now read with the full benefit of hindsight. In later issues there was Harlan Ellison filing a succession of lengthy and inimitable film essays; several pieces by Robert Anton Wilson; and some good music articles with features on Larry Fast (issue 12) and Robert Fripp (issue 14), while Lou Stathis profiled and interviewed Bernie Krause (issue 18), The Residents (issue 19), Patrick Gleeson (issue 22), Jon Hassell (issue 24), Captain Beefheart (issue 25), and everyone’s favourite robots, Kraftwerk (issue 31).

The Internet Archive currently has all the files stuck on a single page so most people will either have to download everything at once (I’d advise using the torrent file) or sample issues at random. Fortunately there’s a very thorough breakdown of the entire run of magazines here for those who prefer to pick through the detail. In the universe next door we’re reading these back issues while floating above the earth in our L5 space colonies.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Science Fiction Monthly

I remember that time well, I was a huge SF fan back then. Still am, but pretty much gave up on recent SF back in the Noughties, when it was simply dire. I lived through that time almost exclusively on a reading diet of second-hand stuff, after deciding I couldn’t stomach any more slipstream, stuff written by people without the slightest science background, and stuff that was somewhat less engaging than a technical manual. Now there is some good SF again, but it has to grow from what was pretty much a wasteland, so it will be a few years before a healthy SF ecosystem flourishes… if it’s allowed to.

What happened? Most of the hard SF writers died off. It was hard for new hard SF writers to find the time; to be proper hard SF, you had to have a techie/science career and find time for writing as well. If you were really good at it, you might become a full-time writer, but that was never achieved, nor the goal, for most of them. By the 80s, it wasn’t any longer very likely that a fully tech/science person would have the spare time. Also, the techie class that was the readership got smaller, as well. Outsource everything technical to China, and surprise surprise, less people understand what hard SF is really about.

There is some hope for a healthy SF ecosystem returning, but to remain realistic, it’s by no means guaranteed. People are now realizing that it does matter if techie skills are in short supply, and maybe we need some more of them. Will they go back to the levels of the 60s? Maybe not. The pool of SF writers might develop from techie bloggers, but again, no guarantees. Some sort of modern equivalent of the SF magazine with science bits needs to appear, something easy for people to dip in their toes and get some recognition, and I’m not aware of that showing up yet. Nowadays, it would be a website, but where is the money to pay for good contributors going to come from? It could happen, but it could also not happen.

SF of the time also had the feel that we needed SF writers to help people navigate the future. It turned out that SF almost died, and people managed to navigate the future technical changes just fine. Plus, the changes turned out to be the Internet and smartphones, which weren’t very much on the SF radar until they were almost upon us. So that feeling of being necessary is gone. Any future healthy SF ecosystem has to be justified on a different premise, or at least modify the original premise somewhat.

But maybe it’s all gone for good, and the revival is just the last gasp. There is no longer a healthy ecosystem for Medieval-style Grail romances, though they made enough of a splash in cuture that new art based on them continues to be made. The same could happen with SF: The good old SF ecosystem may never revive, but it made enough of a splash in the culture that the SF style remains in artform forever, even though it’s mainly a stylistic choice, rather than some sort of quest to consciously build the future.