Regular readers may have noticed my persistent urge to trace the provenance of certain images or designs. The latest candidate is the above illustration of a witches sabbat, a picture familiar to readers of occult histories in addition to appearing on at least two album covers. It’s the use in occult books which no doubt drew it to the attention of composer John Zorn who used it as a cover image in 2004 for his Magick album, one of a series of occult-themed recordings. The album credits the artwork to Gustave Doré, a plausible candidate given the engraving style but I’m familiar enough with Doré’s work to doubt that it was one of his.

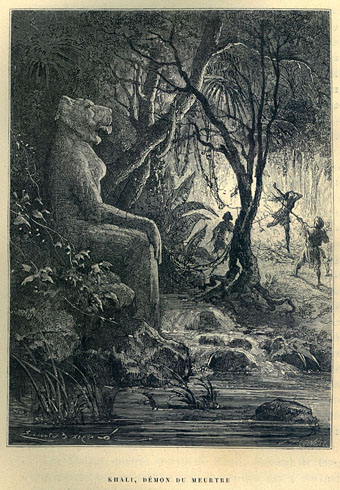

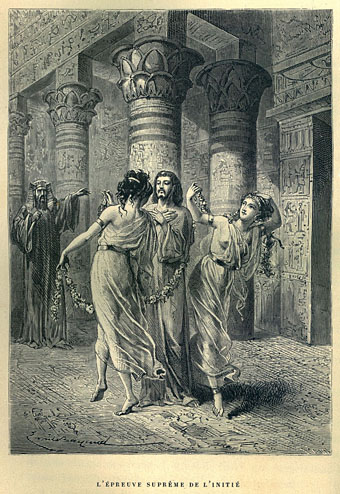

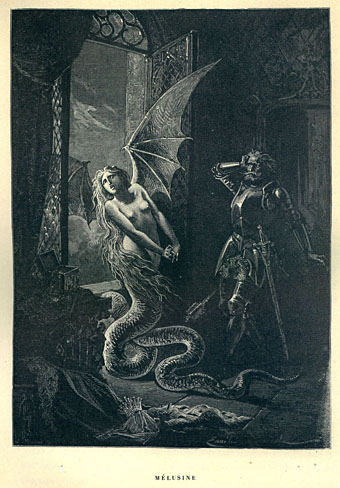

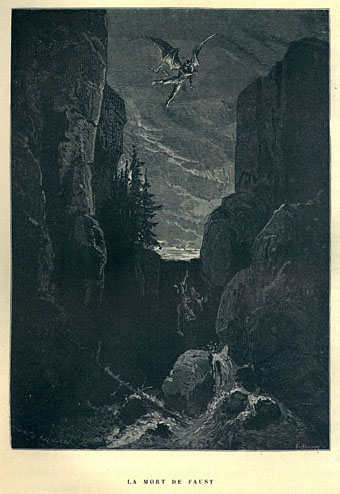

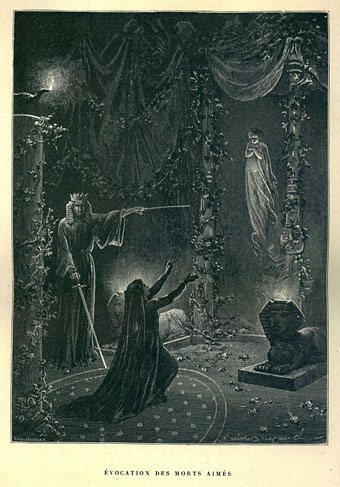

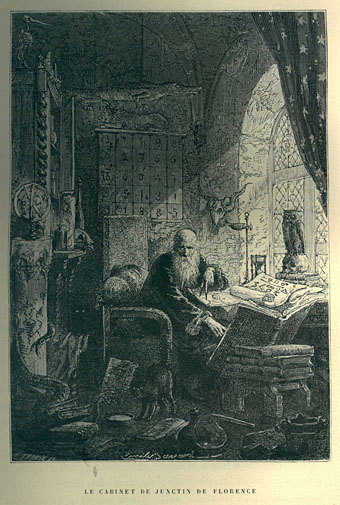

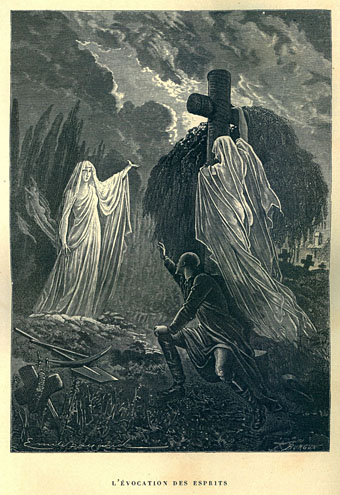

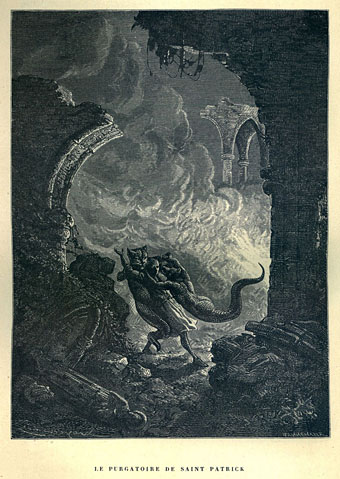

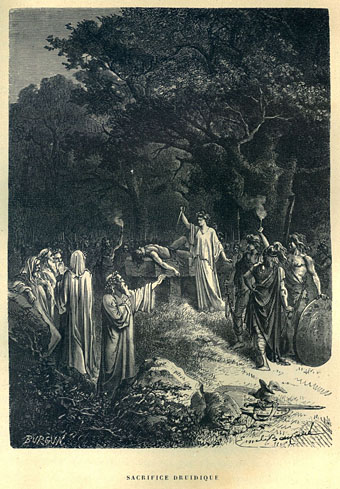

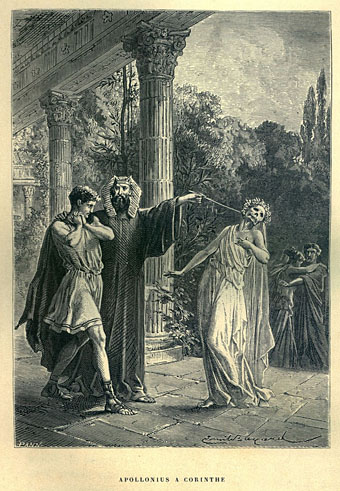

Earlier this week I was looking for more occult-related imagery so finally conducted a proper search for the sabbat picture. The origin is a French volume by Paul Christian, Histoire de la Magie, Du Monde Surnaturel Et de la Fatalite a Travers Les Temps (1870), and the full-page illustrations are by Émile Bayard (1837–1891). The Doré identification was partially correct since Bayard was a contemporary of Doré’s, and the drawings were engraved by François Pannemaker, an engraver who worked on many of Doré’s books as well as the Hertzel editions of Jules Verne. Émile Bayard is one of those artists whose name is unknown today even though people throughout the world would recognise one of his drawings; his illustration of Cosette from Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables provided the face seen on all those posters and hoardings promoting the popular musical.

“Paul Christian” was the nom de plume of Jean-Baptiste Pitois (1811–1877), and his study of occult history was a popular book when it first appeared. I can’t say much about its contents but the illustrations (of which these are a selection via this page) show a range that encompasses various myths and religions as well as the expected variants of Western occultism. I’d seen several of Bayard’s other illustrations in a more recent French history of the occult, where the pictures are uncredited. I’ve suspected for years that they might be by the same artist responsible for the sabbat picture so this discovery has laid another nagging question to rest.

Histoire de la Magie isn’t among the scanned books at the Internet Archive, unfortunately, but a copy may be viewed at Gallica. It’s a shame this is one of Gallica’s older scans which spoils the artwork but you can at least seen the book in full. An English translation was published in the US in 1969, containing notes and additions by living occult experts, but I’ve yet to discover whether this edition retained Bayard’s pictures.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• De Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal

‘To anoint the body and make it shine,

to drink and make thyself divine,

to choose another’s form and make it thine! –

Worship for Satan? Tee Hee hee’ V.Stanshall 1968

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9ro2C_tUSc

Paul Chistian/Pitois of course deserves full credit for the “occultation” of the Tarot, following on in flamboyant fashion from Court de Gebelin. Pitois first published his outlandish theories as fiction, in “Le Petit Homme Rouge des Tuileries”, then later recycled those hermetic and astrological portions as fact in his book on magic. He is also the source of the false description of the Tarot Arcana in the pyramids of Egypt attributed to Iamblichus as well as the terms “major” and “minor arcana” themselves.

JB: Thanks. When I was researching this post I saw Christian/Pitois mentioned on a couple of articles about Tarot history but didn’t read anything in detail.

Even without reading the book the illustrations imply a degree of invention. One of the pictures missing from this post is of Gilles de Rais depicted as…what? Satan-inspired alchemist?

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gilles_De_Rais.jpg

Christian/Pitois certainly was inventive, in fact, many of the more abstruse meanings attached to the Major Arcana can be traced directly back to his books.

As for Gilles de Rais, the charges of witchcraft, satanism and alchemy later took on greater significance in the fertile imagination of the 19th century – see Huysmans’ ‘La-Bas’ (‘Down There’), for instance. Historiographers disagree as to whether there was any truth to that, although they mostly agree on the kidnapping, murder and sadism ones.