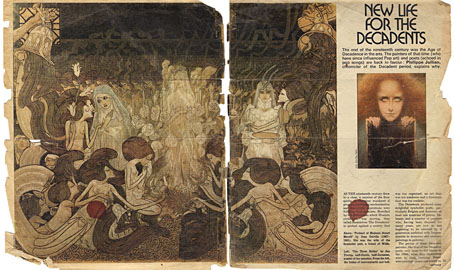

This essay by cult writer Philippe Jullian appeared in an edition of the Observer colour supplement in 1971, shortly after Jullian’s chef d’oeuvre, Dreamers of Decadence, had been published in Britain. Esthètes et Magiciens (1969), as Jullian’s study was titled in France, was instrumental in raising the profile of the many Symbolist artists whose work had been either disparaged or ignored since the First World War. A year after the Observer piece, the Hayward Gallery in London staged a major exhibition of Symbolist art with an emphasis on the paintings of Gustave Moreau; Jullian alludes to the exhibition in his article, and also wrote the foreword to the catalogue. His Observer article is necessarily shorter and less detailed than his introductory essay, emphasising the reader-friendly “Decadence” over the more evasive “Symbolist”. But as a primer to a mysterious and neglected area of art the piece would have served its purpose for a general reader.

Many thanks to Nick for the recommendation, and to Alistair who went to the trouble of providing high-res scans that I could run through the OCR. The translators of the article, Francis King and John Haylock, had previously translated Jullian’s biography of Robert de Montesquiou.

*

New Life for the Decadents

The end of the nineteenth century was the Age of Decadence in the arts. The painters of that time (who have since influenced Pop art) and poets (echoed in pop songs) are back in favour: Philippe Jullian, chronicler of the Decadent period, explains why.

AS THE nineteenth century drew to a close, a number of the finer spirits of the time wondered if progress, increasing mechanisation and democratic aspirations were fulfilling their promises. Horrified by the direction in which Western civilisation was moving, they called themselves “The Decadents” in protest against a society that was too organised, an art that was too academic and a literature that was too realistic.

The Decadents produced some delightful symbolist poets, particularly Belgian and Austrian; at least one musician of genius, Debussy; and a number of painters who, having been despised for many years, are now at last beginning to be admired by a generation surfeited with Impressionists in museums and abstract paintings in galleries.

The genius of these Decadent painters, like that of the Decadent poets, only came to full bloom in the 1890s, when they themselves were in their twenties. Never were painting, music and poetry so close to one another. The gods of the Decadents were primarily Wagner and Baudelaire, then Swinburne and Poe. The Decadent movement, so active all over Europe, turned towards two great sources of inspiration: the Pre-Raphaelites, and a French painter whose glory was for a while eclipsed by the Impressionists but who is now once again accorded his place among the great—Gustave Moreau.

The women whom the Decadents loved and of whom they dreamt resembled the women created 30 years previously by Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Moreau.

Nothing could be more naturalistic than the artistic style elaborated by the Pre-Raphaelites in the middle of the nineteenth century. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s model, inspiration, mistress and finally wife was the sweet and sad Elizabeth Siddal, on whom so many fin-de-siècle ladies had to model themselves on the Continent as did all the aesthetic ladies of England in the 1880s. She posed for Rossetti as Beatrix and as the Belle Dame sans Merci.

She was a rare spirit, about whom everything was nebulous and evanescent: the thick, wild hair; the tunic of a simplicity to challenge the elaboration of the crinolines then in vogue; the frail hands burdened with lilies; the gaze turned towards eternity. She also posed, fully dressed and lying in a bath, her hair outspread around her bloodless face, as Ophelia for another Pre-Raphaelite, Millais. Elizabeth died of pulmonary tuberculosis in 1862.

A macabre episode, which might have been imagined by Poe, was the exhumation of a sheaf of Rossetti’s poems that had been buried in Elizabeth Siddal’s coffin. When this symbol of the New Woman died, the grief-stricken poet had insisted on placing the poems inspired by her under her long hair before the coffin was sealed.

Beata Beatrix (1864–1870) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

In the months that followed, obsessed by her memory, he portrayed her once more as Beatrix. But this time she was a ghostly apparition from another world. It was to be his masterpiece, this Beata Beatrix, eyes closed against a background of a Florence shrouded in mist. The picture is rich in symbols. The bird in it is red, the colour of death; Beatrix’s cloak is green, recalling spring; her dress is purple, the colour of pain.

During this period Rossetti was an assiduous frequenter of seances; but he could no longer write. Friends began to suggest that he should recover the buried poems, until, after years of hesitation, the by now completely neurasthenic Rossetti gave way to the entreaties of Howell—picture dealer, entrepreneur, reputed blackmailer—and entrusted him with the task of exhumation. Mysterious signs—a bell rang apparently without any human agency, a sparrow perched on his hand—led the poet to believe that Elizabeth had given her assent.

On 4 October 1869, at Highgate Cemetery, the coffin was taken out of the earth. A great fire of dead leaves had been lit to dispel any miasma that might escape. In the glow of the flames the body appeared; it was of a radiant beauty. The manuscript was removed. A long lock of golden hair was stuck to it. No Decadent painter has ever depicted a scene so strange. Duly disinfected, the poems were sent to the publisher and when they appeared the following year, they were immensely successful. The tomb was piously closed again and Rossetti now turned to opium in an attempt to relive the whole sombre experience in his dreams.

Thirty years later the French historian Jean Lorrain described the beauty in fashion at that time: “With the disquieting pallor of the Host, an oval face made even thinner by an expression of spirituality and suffering, and seemingly distended eyes of an ultramarine deepening to black, set in circles blue, bruised, speckled with mother-of-pearl, she was the personification, in her fragility and strangeness, of the psychic beauty of the twentieth century. Where had I already seen this delicate nose with its mobile, vibrant nostrils, where the heaving of that flat chest?”

Gustave Moreau, who died in 1897, the same year as Burne-Jones, painted the same themes as the Englishman; but whereas Burne-Jones, with his grisailles and fluid shapes, seemed dedicated to water, Moreau used the colours of fire. The Frenchman’s world is more emphatically directed towards the Orient than the Englishman’s. Although he had been a pupil of Ingres, Moreau considered himself to be the successor of Delacroix, the last grand master of the Renaissance, lost in the modern world in which he was an anachronism. Moreau was indeed a link between “great painting” and “modern painting” of the kind produced by his pupils, Rouault and Matisse.

These last two have since become far more famous than their teacher; but in 1885 Moreau was, like Wagner, a master-magician, revered by all those young people for whom painting must be a guide to a dream and not merely represent a fruit-bowl or a strike of workers.

Confused emotion of this kind is right in a period in which ethics are as much in question as aesthetics, and in a society which boasts of cultivating in turn rare vices and a refined mysticism. The image of civilisations massacred in palaces—Byzantium and Benares are recalled simultaneously—recurs in Moreau’s paintings. The canvases are overloaded with legends, their heroes overloaded with jewels. Here are sirens and wantons trailing their veils in the blood of their victims. Helen and Salomé not merely have the smile of the Giaconda but are the first vampires.

Salomé Dancing before Herod (1876) by Gustave Moreau.

Moreau made this observation of the kind of woman he portrayed time and time again: “Such a creature—bored, capricious, animal in her nature—has grown so weary of having all her desires satisfied that she can take small pleasure in seeing her enemy in the dust.” The almost naked. heroes recumbent at the feet of Moreau’s women, themselves also decked with pearls and flowers, recall Wilde’s line “Each man kills the thing he loves”—for Moreau, with the utmost discretion, loved beautiful young men and disliked women.

The Decadence was, indeed, an extremely homosexual period, with Wilde, Verlaine, Stephan George and Jean Lorrain all in the ascendant. Moreau described his ideal, which he painted in his Tyrtaeus Singing During the Battle, in the following terms: “Tyrtaeus is portrayed as a young man whose features alone are feminine and the beauty of whose body is cast in the classical mould. On the poet’s left, in contrast, is a soft figure—the lyre-carrier, who is at once servant and friend. This figure must have a completely draped aspect and must be very feminine. He is almost a woman, being the only person in the whole ardent throng who understands both the devotion and the suffering of the poet.”

Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra (1875–6) by Gustave Moreau.

Inseparable from these images of male beauty, nearly always represented as dead because of the guilt that it inspires, is the mystic exaltation whereby woman becomes a flower, an asexual allegory, a soul. But the spirit which seeks refuge in chimeras always runs the risk of meeting monsters, and in the Decadence there is a resurgence of legendary creatures: Hydras, Medusas and Sphinxes from antiquity; Unicorns and Tarasques from the Middle Ages; beasts from the Apocalypse. All the Symbolists had recourse to this bestiary when decorating their poems with alarming apparitions that seemed to them to have had their origin in legend but were in fact the creations of their own subconscious minds.

Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra (detail) by Gustave Moreau.

Böcklin, who was on good terms with Moreau, produced some monsters that were as hideous as any Freudian phantasm—Freud was, after all, also a Symbolist. The real monster is woman—Salomé as Huysmans describes her in the following famous passage: “The symbolic deity of indestructible lust, the goddess of immortal Hysteria, the accursed beauty that stands out from all others because of the catalepsy that stiffens her flesh and hardens her muscles; the monstrous beast, indifferent, irresponsible, callous.” This was the same Salomé who was so often portrayed by Moreau and who inspired Wilde’s drama and many of Beardsley’s drawings.

The Gustave Moreau Museum, in the rue de la Rochefoucauld in Paris, houses all these heroic and confused dreams in paradoxically bourgeois and staid surroundings. It is one of the least known and yet one of the strangest places in the capital.

From it will come the works that will be exhibited next year at the Hayward Gallery, together with paintings by Puvis de Chavannes, himself an academic Burne-Jones, and fine lithographs and charcoal drawings by Odilon Redon, who went even further in the direction of the invisible, the monstrous and the mystic, while all the time hating to be classed among the Decadents.

Although the artists who most strongly inspired the Symbolists were English or French, yet the most bizarre painters in fact were born in northern and eastern Europe, where legends have more meaning. Austria produced Klimt, a link between Moreau and the 1920s. Holland produced Toorop, the half-Javanese, who was a great admirer of Burne-Jones and a devotee of the macabre.

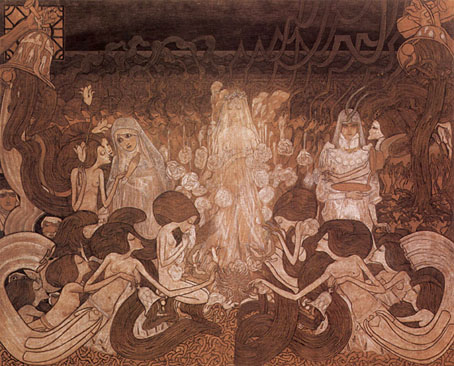

The Three Brides (1893) by Jan Toorop.

The most hectic of all the fin-de-siècle oddities was the journalist Jean Lorrain, who fought a duel with Proust. Here, in a style the contortions of which are marvellously suited to the subject, is what he wrote of Toorop: “A sort of quasi-monastic devilry in a countryside populated with ghosts, flowing ghosts, spewed up, like a wave of leeches, by jangling bells, three women, shrouded in gauze in the manner of Spanish Madonnas, rise up phantom-like. They are the three brides: the Bride of Heaven, the Bride of Earth, the Bride of Hell. The Bride of Hell, with two serpents writhing about on her temples and supporting her veil, has the most attractive countenance, the deepest eyes, the most vertiginous smile that one could ever see…”

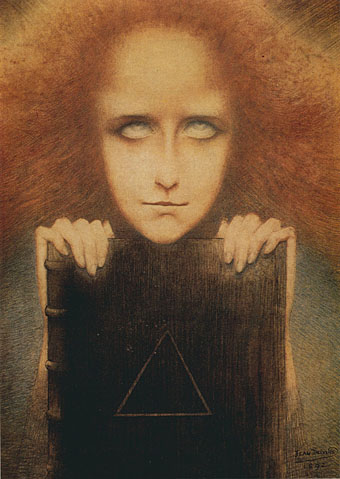

Portrait of Madame Stuart Merrill (1892) by Jean Delville.

Belgium also had painters who both inspired Maeterlinck and were inspired by him. There was, of course, Ensor, whose devilries seem rather vulgar when set beside the grisaille apparitions depicted by our own painters.There was Khnopff, who drew sphinxes in the likeness of Queen Alexandra. An aesthete, who was in love with his sister, Khnopff lived in a vast, old-fashioned mansion, decorated with grey tapestries and mouldings in antique style. Like many of these painters, he despised the century in which he had been doomed to live. There was Delville, who covered huge canvases in his attempt to make a synthesis of Buddhism and Christianity. He finished by becoming a theosophist and his last works are deplorable.

Bruges was extremely fashionable with the aesthetes, almost as much as Venice; but it was a less amusing place. In this connection it should be noted that Visconti, in his film ‘Death in Venice’, has wonderfully expressed the poetically macabre character of the stricken city. Tadzio’s face is the one that all the painters of this ambiguous epoch dreamt about; and the fate of the composer at the end of the film explains these lines of the German Von Platen: “He who has seen Beauty with his eyes/Is predestined for Death.”

More than manifestoes, literary schools or magazines, what united the Symbolists, the Decadents and all those who were disgusted with the period was a community of taste of the kind that assembled a group around Rilke in Prague and around Ruben Dario in Cuba. They loved closed eyes; a finger on pale lips; dishevelled hair; dead roses; naked feet; a glove lying abandoned in an empty house; a piano on which Schubert is being played behind closed shutters; silhouettes vanishing into mist; faces and old buildings reflected in the dead waters of canals; and princesses. Princesses abound in Maeterlinck’s plays and in the pictures of his artist friends—Yseult, Melisande, Oriane, Melusine.

These Decadents imagined and even lived adventures still more sombre. Black masses, sorcery, love-potions and witches’ sabbaths enjoyed in this period a sinister revival. Aleister Crowley was the incarnation of all this dark side of the Nineties.

Many poems and pictures of the time portray a princess staring at her reflection in a pool choked with dead leaves. Others depict princesses like Poppaea, Cleopatra or Theodora from the Orient or Byzantium. At the feet of such daughters of empresses masochists like Swinburne would willingly die in ecstatic agony. The Giacondas had become vampires. Bats flitted through twilights of blood. Out of swamps unwound the kind of sinuous, tortuous, etiolated plants that one finds in the designs of Beardsley, along the length of houses constructed by Horta, on Gallé’s vases and in Mucha’s posters.

Something more than fashion and caprice have led to a revived interest in painting that was disparaged for 60 years. In the United States and England there has been a strong resurgence of interest in magic and ritual, as is borne out by the popularity of religio-erotic art and by the appearance in underground magazines of illustrations that evoke the same kinds of myth as once inspired Odilon Redon and Toorop. Mythological monsters are quite at home in science fiction; and the use of hallucinogens gives to the most worn-out myths a terrifying reality.

Yes, there is here something much more profound than a simple return to fashion. Just as artists around 1890 were horrified by industrial civilisation, so many of us today cannot tolerate our consumer society. Abstract art bores us in the same way that realism once bored the “dream” painters. We want an art that will carry us away from the world, an art that is a constant rejection of our daily lives, an art that gratifies Wilde’s wish to leave the world of Zola and our own wish to leave the world of Sartre. As Wilde put it: “And when that day dawns, or sunset reddens, how joyous we shall all be! Facts will be regarded as discreditable, Truth will be found mourning over her fetters, and Romance, with her temper of wonder, will return to the land… Over our heads will float the Blue Bird singing of beautiful and impossible things, of things that are lovely and that never happen, of things that are not and should be.”

This article was translated from the French by Francis King and John Haylock.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Philippe Jullian, connoisseur of the exotic

Vive Philippe!

>http://www.noveporte.it/dandy/dandies/img/jullian11.jpg

et Messr Coulthart

(belated thanks for Austen PERRAULT; bloody JUGEND cupids; and so much more on a constant basis)

Ha, that’s a photo I’d not seen before. When Jullian wasn’t cross-dressing—which he apparently did a fair amount of—he apparently favoured very English tweed suits. Odd to find a French Anglophile, the situation is more usually the reverse.

The translators of the article, Francis King and John Haylock

Different from Francis X. King the occult writer and Crowley biographer, although equally dead.

A copy of “Dreamers of Decadence” somehow found its way into the library of the high school I attended, introducing me at a vulnerable age to that artistic direction.

a group around Rilke in Prague

It may just be me, but Rilke doesn’t seem to be identified as a ‘Prague’ writer; unlike Meyrink and Perutz and Kafka, he’s not part of the brand. Perhaps he left the place too early.

Thank you for this piece John, I thoroughly enjoyed it.

herr doktor bimler: I only discovered recently that there were two Francis Kings, always thought they were the same writer. Matters aren’t helped by all the occult Kings being named at the time without the distinguishing X.

This is great- the original Observer article had become so fragile I hadn’t read it for many years- so it is fascinating to be able to read it properly and see what so fascinated my teenage self…

In 1983, I photocopied several of the images from the Observer article, the Three Brides for example, and recycled them in my pyschedelic goth punk magazine the Encyclopaedia of Ecstasy Volume One. Now scanned and posted on my blog.

http://greengalloway.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/enyclopaedia-of-ecstasy-1983.html

Thank you for this. Interesting. I would also strongly recommend Rapetti’s recent book on Symbolism. http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn06/50-autumn06/autumn06review/153-symbolism-by-rodolphe-rapetti

A little Jullian anecdote: recently I spoke to someone who had personally known Claartje Rijnbende (died 1971), Carel de Nerée’s (died 1909) more or less secret love from around 1900 who was the inspiration for a.o. his drawing Introduction, see: http://www.johncoulthart.com/feuilleton/2010/09/25/the-art-of-karel-de-neree-tot-babberich-1880%E2%80%931909/ He told me that when in 1968 Jullians biography of De Montesquieu appeard she and allmost all her chic The Hague lady friends who actually experienced the 1900s all read his ‘cult book.’ Actually, he told me she told him Carel de Nerée and she read Montesquieu’s poems together, but that’s a aside.

Alistair: Thanks again for sending the scans, it’s great being able to resurrect lost writings in this way. I corrected a couple of typos: Aleister Crowley’s first name was misspelled, and the typesetters put a comma between Odilon and Redon. Also managed to restore two missing words where he’s talking about Klimt by seeing what he says in the book. He makes the same point in each, that Klimt was “a link” (the missing words) between two eras.

Sander: I’m sure the biography would have been of interest to anyone who lived through that time. The book is a little rambling compared to his later works, the Wilde biography is much better.